NJ Spotlight, May 7, 2014

By JON HURDLE

Study by group of scientists and other experts offers specific forecast of extreme weather’s impact on Northeast, rest of U.S.

New Jersey and the rest of the nation’s Northeast are already experiencing the effects of climate change and can expect more heat waves, downpours, floods and storms in the future, according to a major national report issued on Tuesday.

The National Climate Assessment said that longstanding predictions of climate change are now a reality, causing seas to rise, precipitation patterns to shift and temperatures to soar, with resulting damage to infrastructure, homes and human health.

“This report shows that climate change is here and now, and matters to each one of us no matter what part of the country we live in,” Katharine Hayhoe, director of the Climate Science Center at Texas Tech and a contributor to the report, said during a conference call with reporters.

The report was written by the U.S. Global Change Research Program, a collaboration of 13 federal departments and some 300 scientists and other experts. The program was initiated during the administration of President George H.W. Bush.

Northeast temperatures rose an overall 2 degrees Fahrenheit between 1895 and 2011 while precipitation increased by 10 percent, or about 0.4 inch a decade, the report said. The region’s seas have risen about a foot, or 4 inches more than the global average, since 1900.

By mid-century, New Jersey and surrounding states can expect to have 60 more days per year when temperatures exceed 90 degrees Fahrenheit than they did at the end of the 20th century.

By the 2080s, the average temperature for the Northeast region is expected to rise by 4.5 to 10 degrees if global carbon emissions continue to rise at the current rate, but a substantial cut in emissions could limit the temperature increase to 3 to 6 degrees, the report said.

Less than a week after a record-breaking rainfall in some areas of the mid-Atlantic, the report forecast a continuing increase in extremely heavy downpours. It noted that between 1958 and 2010 there was a 70 percent increase in the amount of rain that fell during such downpours.

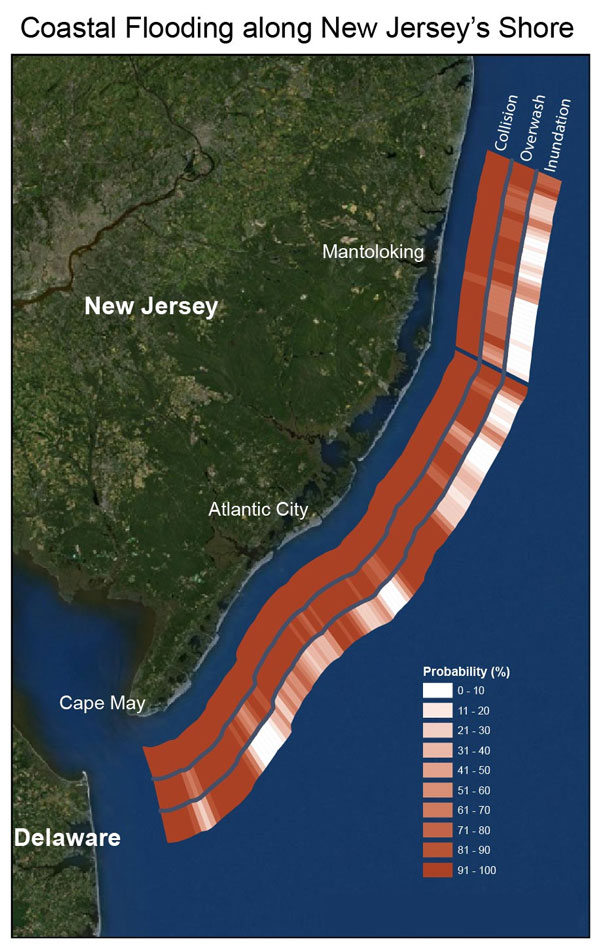

And, some 18 months after Sandy, the study projected increased coastal flooding as a result of sea-level rise, even without storms.

“Sea-level rise of two feet, without any changes in storms, would more than triple the frequency of dangerous coastal flooding throughout most of the Northeast,” the report said.

It noted that global sea levels are expected to rise 1 to 4 feet by 2100, depending on the rate at which the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets melt. But, as already projected by Princeton-based researcher Climate Central and others, the increase in New Jersey and other mid-Atlantic states will be greater, mostly due to land subsidence.

It said individual hurricanes like Sandy can’t be directly attributed to climate change but called them “teachable moments” that show the region’s vulnerability to extreme storms.

The region will also experience increased river flooding because of more severe rainstorms, the report said. It focused only on the United States, and followed two global reports from the UN’s International Panel on Climate Change earlier this year.

Infrastructure at risk from rising waters includes airports, roads and rail lines. A 2 -foot rise in sea level in New York – entirely possible before the year 2100 — would flood or render unusable more than 200 miles of road, some 700 miles of railroad tracks and 539 acres of airport runway, the report said. It said effects would be similar in low-lying areas of other states.

In the Northeast, heat waves are likely to be especially dangerous to vulnerable populations such as the elderly, the very young, and the poor, the report said. The highest temperatures will be felt in the region’s big cities, where ground-level ozone and other pollutants are likely to lead to increased hospitalizations, it said.

By the 2080s, heat-related deaths in Manhattan are expected to be 50 percent to 91 percent higher than they were in the 1980s, the report said, citing one study.

People who live in coastal areas are particularly vulnerable to storms and sea-level rise, the report said. It noted that 1.6 million Northeast residents live in areas defined by the Federal Emergency Management Agency as 100-year flood zones – where coastal flooding is deemed to have a 1 percent chance of happening in a given year – and that 63 percent of those people live in New Jersey or New York.

It predicted that people in the 100-year zone will experience more frequent floods, and that those who currently live outside the zone will find themselves within it. Across the region, between 450,000 and 2.3 million people are at risk from a 3-foot rise in sea level, the report said.

Hurricane Sandy offered a painful preview of the devastation wrought by bigger storms, and their effects will be amplified by higher sea levels, the report said.

Dr. Radley Horton, a research scientist at Columbia University and the lead author of the study’s chapter on the Northeast, called the report the “most comprehensive” national climate assessment ever released.

“It needs to speak to all Americans because one of its key points is that we are already seeing the effects of climate change,” he told reporters. The effects are directly linked to a 40 percent increase in greenhouse gases brought about by human activity since the start of the industrial revolution, he said.

The Northeast is particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change because of its aging infrastructure, such as Interstate 95, Amtrak rail lines and numerous electrical substations, Horton said.

“As sea levels rise, we are going to see these multiple system failures,” he said. “If part of that electrical system goes down, it will impact our ability to pump water out of the subway.”

The predicted increase in heavy downpours is also a threat to rural areas of the Northeast where infrastructure, agriculture and towns are clustered in valleys, and are especially vulnerable to flooding, Horton said.

Despite the dire predictions, the Northeast has begun to work on how to adapt to climate change, Horton said. He said all but two of the region’s states now have climate action plans, cities are developing heat action plans, and some local governments and residents are taking practical measures like elevating coastal houses.

New Jersey does not have a climate action plan.

“Mitigation strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and to adapt to climate change are well under way in the region,” Horton said.

But he warned that authorities are only just beginning to work on the problem.

“We need to emphasize that implementation of all these strategies is at a very early stage,” he said.

Horton and other co-authors called for a move away from fossil fuels and toward alternatives such as wind and solar to reduce carbon emissions and lessen the effects of climate change in the future.

“All is not lost,” said Hayhoe of Texas Tech. “The choices that we are making today will determine the changes and the impacts that we will live through in the future.”

Climate Central’s Ben Strauss, whose group in April published an updated online tool to gauge the localized effects of sea-level rise across New Jersey, said the federal report moves climate change from the future to the present.

“This report really highlights that the impacts of climate change are already with us now, and they affect people in every part of the nation,” he said.

Environmentalists seized on the report as an opportunity to renew their calls for New Jersey to re-enter the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, an effort to cut regional carbon emissions, from which New Jersey exited in May 2011.

“As we approach the third anniversary of Gov. Christie’s decision to pull us out of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative … the time for action is now to deal with global warming pollution in New Jersey,” said Doug O’Malley, director of Environment New Jersey.

Jeff Tittel, director of the New Jersey Sierra Club, accused Gov. Christie of denying climate change, and said the governor has cut emissions-reduction goals in the state’s Energy Master Plan while closing the state’s office of climate change.

“It’s time for Governor Christie to accept that climate change is real and to start tackling the issue instead of pleasing the Koch brothers,” Tittel said, in a reference to the prominent Republican Party donors.

Neither Michael Drewniak, a spokesman for Gov. Christie, nor Jim Benton, executive director of the New Jersey Petroleum Council, responded to requests for comment.

NJEJA Letter Archive on the EJ Law Rules