We craft model legislation for EJ communities throughout New Jersey and statewide.

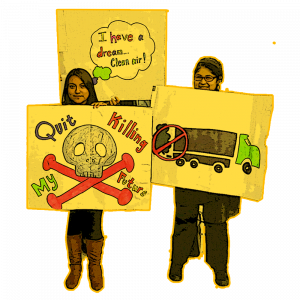

Air pollution is one of the most serious environmental health threats in our state and disproportionately impacts EJ communities. There is evidence that in New Jersey, EJ communities suffer from a disproportionate amount of pollution when compared to other communities in the state.

Fine particulate matter air pollution has been estimated to cause approximately 200,000 premature deaths in the United States annually. This deadly pollutant is linked to cardiovascular disease and a variety of pulmonary disorders including lung cancer, asthma and decreased lung function in children. EJ communities suffer from exposure to a multitude of air pollution sources and the cumulative impacts from air pollutants such as fine particulate matter (PM) that includes diesel particulates; criteria air pollutants that include ozone, lead and the aforementioned fine particulate matter; and hazardous air pollutants.

Cumulative impacts

The issue of cumulative impacts focuses on developing ways to address multiple sources of pollution in environmental justice (EJ) communities (i.e. Indigenous communities, communities Of Color and low-income communities). Of most concern are the detrimental impacts that a combination of pollutants can have on the health of community residents.

What are cumulative impacts?

Cumulative impacts can be defined as the impacts caused by multiple pollutants, often emitted by multiple sources of pollution, and their interaction with each other and with any social vulnerabilities that exist in a community. The term is also frequently used to refer to the risks associated with the pollutants and the aforementioned interactions.

The following are examples of cumulative impacts policies. The first two come from New Jersey and the third is a national policy. This document is not intended to be a comprehensive compilation of cumulative impacts policies. Instead it offers examples of the types of policies that might be developed.

- Identify EJ and/or overburdened neighborhoods using a screening tool.

- There will be overlap between these two types of neighborhoods.

- Protect these neighborhoods from new sources of pollution by not granting a pollution permit to a new large polluting source unless they can demonstrate they will not increase the amount of pollution in the neighborhood by showing either:

- They will have no pollution emissions; or

- They will reduce existing pollution in the neighborhood by a greater amount than any pollution emissions they might have.

- Reduce existing pollution by not renewing pollution permits of major polluters unless they show they will reduce pollution in the neighborhood by either:

- Reducing their own emissions; or

- Reducing existing pollution in the neighborhood by a greater amount than their own pollution emissions.

- Provide incentives that would address other quality of life issues such as:

- Attracting non-polluting businesses that produce job and entrepreneurship opportunities;

- Ensuring the availability of nourishing, affordable, food;

- Ensuring sufficient green space.

Note: A (2)(b) and (3)(b) describe what are commonly referred to as “offsets” and the EJ community generally opposes them (e.g., offsets used in cap and trade), because they do not protect specific neighborhoods or locations. The offsets recommended here are specific to the neighborhoods likely to be affected by the polluter and therefore distinguishable from offsets as they are typically conceptualized. But the policy could be implemented without the offsets if the neighborhood still has reservations concerning them. `

- The ordinance was adopted by the City of Newark in October 2016 after over three years of advocacy and organizing.

- The adopted ordinance is an altered version of a model EJ and Cumulative Impacts ordinance that took a year to develop.

- The partners would like to obtain the resources to evaluate the ordinance for effectiveness and to determine if any changes need to be made.

- Substantive parts of the ordinance:

- City must create a “natural resources index” that lists the major sources of pollution, their location along with demographic data, and the type and amount of pollution they emit.

- Applies to commercial and industrial activities that need an environmental permit or are seeking a site plan approval or variance;

- A commercial activity must submit a pollution checklist that provides the type and amount of pollution the activity will emit.

- An industrial activity must complete the checklist as well as estimates of other impacts such as employment opportunities to be generated.

- The Newark zoning ordinance has been amended to prohibit certain uses and make others conditional.

- The purpose of the ordinance is to provide information to city staff, city committees and boards, and city residents so they can make better informed decisions as to whether they should support or oppose a proposed new activity.

- This is a federal bill from Senator Booker and Representative Ruiz.

- A permit will not be issued or renewed under the Clean Air or Clean Water Act if, due to cumulative impacts, there is not a reasonable certainty of no harm.

- There are other parts of the bill that address other issues besides cumulative impacts.

- A permit can be denied if, due to cumulative impacts, permit approval would pose an unreasonable health risk to the residents of a burdened community.

- A burdened community is defined as a census tract in the lowest 33% of census tracts in the State in median household income.

- NJEJA, the Ironbound Community Corporation and allies are urging the sponsors of the Bill to consider a different standard than “unreasonable risk.”

NJ Environmental Justice Bill (s232)

Environmental Justice & Cumulative Impacts Ordinance in the City of Newark

Air Pollution

Air pollution is one of the most serious environmental health threats in our state and disproportionately impacts EJ communities. There is evidence that in New Jersey, EJ communities suffer from a disproportionate amount of pollution when compared to other communities in the state.

Fine particulate matter air pollution has been estimated to cause approximately 200,000 premature deaths in the United States annually. This deadly pollutant is linked to cardiovascular disease and a variety of pulmonary disorders including lung cancer, asthma and decreased lung function in children. EJ communities suffer from exposure to a multitude of air pollution sources and the cumulative impacts from air pollutants such as fine particulate matter (PM) that includes diesel particulates; criteria air pollutants that include ozone, lead and the aforementioned fine particulate matter; and hazardous air pollutants.

Local air pollution generated by trucks in EJ communities is a major problem that must be addressed. Policymakers must develop innovative strategies to reduce diesel emissions not only from buses but also from trucks that frequent EJ neighborhoods and that are part of a state’s private truck fleet.

The work above is referenced from previous NJEJA documents. For more details and information click here.

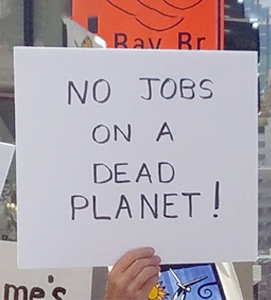

As a member organization of the Coalition for Healthy Ports, NJEJA is actively supporting the campaign for “Good Jobs, Healthy Neighborhoods, & a Clean Environment” for Newark, NJ residents. The priority objectives of this campaign include equitable compensation for the city and environmental mitigation policies, like a ban on dirty pre-2007 diesel trucks and Zero Emissions standard for port operations.

Port Newark and Port Elizabeth bring goods into the U.S. from overseas. Trucks carry the goods from the ports to their final destination, or to warehouses where they are stored temporarily. At every step of the process, workers are exploited (low wages, few or no benefits) and pollution is created for the people of Newark, Elizabeth, Bayonne, East Orange, and surrounding communities.

Now the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey has announced plans to double or triple the size of the ports. The Panama Canal has been widened, allowing for bigger ships. But those bigger ships can’t get into Port Newark because they cannot pass under the Bayonne Bridge. Therefore, to expand the Ports, the Bayonne Bridge must be raised — thus expanding the truck traffic, and associated pollution, in Newark and surrounding areas.

CHPs released a Public Health Report on Impacts of rolling back Truck Ban of Port of New York & New Jersey Clean Trucks Program

Check out this Fact Sheet on Report Findings and Demands

CHP made available a comprehensive policy briefing book for NJ’s gubernatorial candidates on measures needed to address the port’s impacts on public health, communities’ quality of life, working conditions, and good governance. Find the Report Here

New Jersey should implement the Coalition for Healthy Ports Clean Air Plan which includes:

- Developing a bi-state plan for tackling emissions from the freight sector. This plan should include bi-state regulatory proposals, incentives and a robust public participation process, including (1) quantification of the emissions from freight operations in the bi-state area, localized health risks, and the economic benefits associated with reducing diesel pollution; (2) establishing emissions reduction and health risk goals; and (3) identifying the strategies and funding necessary to meet those goals. This type of freight plan can help meet new climate and clean air goals and create incentives and funding for truck fleet turnovers with an eye towards creating a zero emission passenger and container movement system by 2035.

- Enacting a Clean Container Exemption Fee established through legislation that requires any pre-2010 truck engines operating in the seaports to pay a fee that will fund the capitalization of post 2010 truck engines that serve in the drayage industry.

- Reinstating the pre-2007 engine truck ban at the port (initially approved by PANYNJ in 2009), and transition the drayage fleet to 2010 and newer engines. The structure of the ban will ensure that the drivers are not paying for the new trucks.

- Instituting Shore Power or air pollution capture technologies for ships docked at seaports.

- Promptly reviewing California’s freight related emissions reductions programs and adopting the following diesel emission reduction policies:

- Truck Regulations that reduce emissions of PM, and nitrogen oxides and other criteria air pollutants, from in-use heavy-duty diesel-fueled vehicles.

- At-Berth regulations to establish airborne toxic control measures for auxiliary diesel engines operated on ocean-going vessels at-berth. New Jersey Environmental Justice Alliance.

- Transport Refrigeration Unit Airborne Toxic Control Measure to establish airborne toxic control measures for in-use diesel-fueled transport refrigeration units (TRU) and TRU generator sets, and facilities where TRUs operate.

- Cargo Handling Equipment Regulation for mobile cargo handling equipment at ports and intermodal rail yards.

- Commercial Harbor Craft Regulation to establish airborne toxic control measures for commercial harbor craft.

Rutgers University’s Center for Environmental Exposure and Disease (CEED), with NJEJA, Ironbound Community Corporation, and Clean Water Action, hosted the “Public Health and Our Ports Conference and Tour” at the Rutgers Law School in Newark. CEED has been working on the public health impacts of NY/NJ port activities on port-adjacent communities. The overall goal of the conference was to articulate solutions that improve the health and well-being in affected communities. The conference engaged more than 100 stakeholders, including public policy thought leaders, environmental and public health organizations, and academics.

As a steering committee member organization of the Coalition for Healthy Ports (CHPs), NJEJA is actively supporting the campaign for equitable, transparent operations at the Port Authority of New York-New Jersey. While broadly promoting environmental and economic justice in PANYNJ operations and related industries, some specific objectives of the campaign includes: equitable compensation for the city; environmental mitigation policies like a ban on dirty pre-2007 diesel trucks; and a Zero Emissions standard for port operations. In an effort to achieve these aims, NJEJA has regularly participated in direct engagement with officials from EPA Region 2 and PANYNJ to express our concerns and desired outcomes.

Local air pollution generated by trucks in EJ communities is a major problem that must be addressed. Policymakers must develop innovative strategies to reduce diesel emissions not only from buses but also from trucks that frequent EJ neighborhoods and that are part of a state’s private truck fleet.

The work above is referenced from previous NJEJA documents. For more details and information click here.

As a member organization of the Coalition for Healthy Ports, NJEJA is actively supporting the campaign for “Good Jobs, Healthy Neighborhoods, & a Clean Environment” for Newark, NJ residents. The priority objectives of this campaign include equitable compensation for the city and environmental mitigation policies, like a ban on dirty pre-2007 diesel trucks and Zero Emissions standard for port operations.

Port Newark and Port Elizabeth bring goods into the U.S. from overseas. Trucks carry the goods from the ports to their final destination, or to warehouses where they are stored temporarily. At every step of the process, workers are exploited (low wages, few or no benefits) and pollution is created for the people of Newark, Elizabeth, Bayonne, East Orange, and surrounding communities.

Now the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey has announced plans to double or triple the size of the ports. The Panama Canal has been widened, allowing for bigger ships. But those bigger ships can’t get into Port Newark because they cannot pass under the Bayonne Bridge. Therefore, to expand the Ports, the Bayonne Bridge must be raised — thus expanding the truck traffic, and associated pollution, in Newark and surrounding areas.

New Jersey should implement the Coalition for Healthy Ports Clean Air Plan which includes:

- Developing a bi-state plan for tackling emissions from the freight sector. This plan should include bi-state regulatory proposals, incentives and a robust public participation process, including (1) quantification of the emissions from freight operations in the bi-state area, localized health risks, and the economic benefits associated with reducing diesel pollution; (2) establishing emissions reduction and health risk goals; and (3) identifying the strategies and funding necessary to meet those goals. This type of freight plan can help meet new climate and clean air goals and create incentives and funding for truck fleet turnovers with an eye towards creating a zero emission passenger and container movement system by 2035.

- Enacting a Clean Container Exemption Fee established through legislation that requires any pre-2010 truck engines operating in the seaports to pay a fee that will fund the capitalization of post 2010 truck engines that serve in the drayage industry.

- Reinstating the pre-2007 engine truck ban at the port (initially approved by PANYNJ in 2009), and transition the drayage fleet to 2010 and newer engines. The structure of the ban will ensure that the drivers are not paying for the new trucks.

- Instituting Shore Power or air pollution capture technologies for ships docked at seaports.

- Promptly reviewing California’s freight related emissions reductions programs and adopting the following diesel emission reduction policies:

- Truck Regulations that reduce emissions of PM, and nitrogen oxides and other criteria air pollutants, from in-use heavy-duty diesel-fueled vehicles.

- At-Berth regulations to establish airborne toxic control measures for auxiliary diesel engines operated on ocean-going vessels at-berth. New Jersey Environmental Justice Alliance.

- Transport Refrigeration Unit Airborne Toxic Control Measure to establish airborne toxic control measures for in-use diesel-fueled transport refrigeration units (TRU) and TRU generator sets, and facilities where TRUs operate.

- Cargo Handling Equipment Regulation for mobile cargo handling equipment at ports and intermodal rail yards.

- Commercial Harbor Craft Regulation to establish airborne toxic control measures for commercial harbor craft.

Rutgers University’s Center for Environmental Exposure and Disease (CEED), with NJEJA, Ironbound Community Corporation, and Clean Water Action, hosted the “Public Health and Our Ports Conference and Tour” at the Rutgers Law School in Newark. CEED has been working on the public health impacts of NY/NJ port activities on port-adjacent communities. The overall goal of the conference was to articulate solutions that improve the health and well-being in affected communities. The conference engaged more than 100 stakeholders, including public policy thought leaders, environmental and public health organizations, and academics.

As a steering committee member organization of the Coalition for Healthy Ports (CHPs), NJEJA is actively supporting the campaign for equitable, transparent operations at the Port Authority of New York-New Jersey. While broadly promoting environmental and economic justice in PANYNJ operations and related industries, some specific objectives of the campaign includes: equitable compensation for the city; environmental mitigation policies like a ban on dirty pre-2007 diesel trucks; and a Zero Emissions standard for port operations. In an effort to achieve these aims, NJEJA has regularly participated in direct engagement with officials from EPA Region 2 and PANYNJ to express our concerns and desired outcomes.

As part of CHPs, we are active members of the Moving Forward Network (MFN), a national coalition that organizes efforts across states and regions to reduce pollution and public health impacts related to the movement of goods and freight.

NJEJA partnered with the New Jersey League of Conservation Voters Education Fund to create a soon to be released report on Natural Resources Damages and EJ community engagement. Laureen and NJEJA Board Member, Priscilla Hayes, examined practices that determine: which ‘injuries’ are selected for legal action; how the impacts of the ‘injuries’ are valued when settlements are reached; what remediating projects are selected and how they are implemented.” New Jersey LCVEF led the effort to get the issue on the ballot in November 2017. Voters indicated a preference for implementation of restoration projects as close as possible to the site of the original injury; nexus to injury is crucial for EJ Communities, disproportionately impacted by environmental pollution.

Climate Change

Climate change mitigation and adaptation policies should be used to address both climate and disproportionate pollution burdens in vulnerable EJ communities. Because frontline communities feel the double bind of increased risk and increased vulnerability from climate change while contributing the least to this global phenomenon – it is imperative that any climate policies directly incorporate EJ and equity.

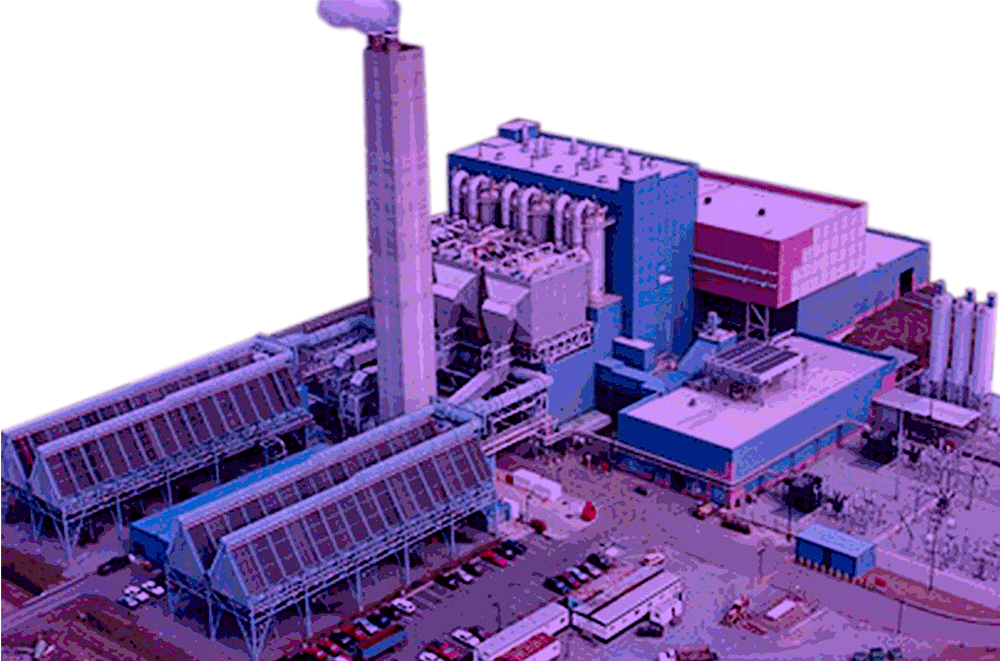

NJEJA has developed policy that calls for power plants that are either located in EJ communities, or whose air pollution emissions significantly impact EJ communities, to be required to reduce those emissions. The goal of this policy is to reduce greenhouse gas co-pollutants, such as fine particulate matter, that are detrimental to the health of residents who live near the plants. These co-pollutants are part of the disproportionate pollution burdens affecting EJ communities and thus reducing them also diminishes the burdens.

This recommendation is discussed in more detail in the law review article Achieving Emissions Reductions for Environmental Justice Communities Through Climate Change Mitigation Policy written by NJEJA Board Chair Dr. Nicky Sheats Esq.

NJEJA opposes carbon-trading schemes at least partly because they do not guarantee emissions reductions from any particular facility and therefore cannot ensure they will result in the reductions sought by EJ advocates and organizers in low-income communities and communities Of Color.

Because carbon trading does not guarantee emissions reductions in EJ communities, or from plants located at any particular location, and for other reasons, NJEJA has opposed the State of New Jersey re-entering the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). However, since the state decided to re-enter RGGI over EJ objections, NJEJA has advocated that New Jersey should make the carbon-trading system more EJ friendly by establishing Mandatory Emissions Reductions on power plants located in EJ communities, or whose emissions significantly impact EJ communities.

We also again oppose incineration, including waste to energy incineration, and biomass burning since either they have already inflicted, or have the potential to inflict, negative impacts on EJ communities.

The work above is referenced from previous NJEJA documents. For more details and information click here.

NJEJA and the Center for American Progress (CAP) co-hosted the first-ever statewide New Jersey Environmental Justice and Climate Summit on April 4th at the Mercer County Community College in Trenton. The summit goal was to bring together state officials, members of Congress, and members of the environmental justice community to discuss solutions to pollution and climate change impacts in New Jersey’s communities of color, low-income neighborhoods, and Indigenous communities. The summit was held on the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. to create an opportunity to reflect on King’s environmental legacy; encourage Gov. Phil Murphy to reduce carbon pollution and associated co-pollutants; prepare for climate change effects; expand access to clean energy; and address cumulative pollution impacts in EJ communities.

NJEJA continued its climate resilience work through the statewide Sandy Climate Justice Roundtables and three subcommittees of more than 50 organizations and individuals: Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Community-led Climate Resilience, and Climate Justice Curriculum.

NJEJA also prepared a summary of policy work under the initiative, including the history, implementation and future of the cumulative impacts ordinance, for the Kresge site visit on July 12 and 13, 2018. Kresge conducted staff interviews with NJEJA Newark Organizer, Nicole Scott Harris, and partner agency interviews with Stephanie Greenwood at the Victoria Foundation and Nathaly Agosto Filion at the City of Newark.

- 11,825 gallons of stormwater were diverted from the sewer system;

- 30 trees were planted to improve aesthetics, reduce ambient temperatures, and reduce the impacts of flash flooding.

- 9000 square feet of cool roofs were created with reflective paint, to lower indoor temperatures and electricity bills.

- 136 catch basins were adopted and 640 pounds of debris diverted from the sewer system

- 76 rain barrels were installed to capture and slow storm water that floods local streets and reuse non-potable water.

This recommendation is discussed in more detail in the law review article Achieving Emissions Reductions for Environmental Justice Communities Through Climate Change Mitigation Policy written by NJEJA Board Chair Dr. Nicky Sheats Esq.

NJEJA opposes carbon-trading schemes at least partly because they do not guarantee emissions reductions from any particular facility and therefore cannot ensure they will result in the reductions sought by EJ advocates and organizers in low-income communities and communities Of Color.

Because carbon trading does not guarantee emissions reductions in EJ communities, or from plants located at any particular location, and for other reasons, NJEJA has opposed the State of New Jersey re-entering the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI). However, since the state decided to re-enter RGGI over EJ objections, NJEJA has advocated that New Jersey should make the carbon-trading system more EJ friendly by establishing Mandatory Emissions Reductions on power plants located in EJ communities, or whose emissions significantly impact EJ communities.

We also again oppose incineration, including waste to energy incineration, and biomass burning since either they have already inflicted, or have the potential to inflict, negative impacts on EJ communities.

The work above is referenced from previous NJEJA documents. For more details and information click here.

NJEJA and the Center for American Progress (CAP) co-hosted the first-ever statewide New Jersey Environmental Justice and Climate Summit on April 4th at the Mercer County Community College in Trenton. The summit goal was to bring together state officials, members of Congress, and members of the environmental justice community to discuss solutions to pollution and climate change impacts in New Jersey’s communities of color, low-income neighborhoods, and Indigenous communities. The summit was held on the 50th anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. to create an opportunity to reflect on King’s environmental legacy; encourage Gov. Phil Murphy to reduce carbon pollution and associated co-pollutants; prepare for climate change effects; expand access to clean energy; and address cumulative pollution impacts in EJ communities.

NJEJA continued its climate resilience work through the statewide Sandy Climate Justice Roundtables and three subcommittees of more than 50 organizations and individuals: Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, Community-led Climate Resilience, and Climate Justice Curriculum.

NJEJA also prepared a summary of policy work under the initiative, including the history, implementation and future of the cumulative impacts ordinance, for the Kresge site visit on July 12 and 13, 2018. Kresge conducted staff interviews with NJEJA Newark Organizer, Nicole Scott Harris, and partner agency interviews with Stephanie Greenwood at the Victoria Foundation and Nathaly Agosto Filion at the City of Newark.

- 11,825 gallons of stormwater were diverted from the sewer system;

- 30 trees were planted to improve aesthetics, reduce ambient temperatures, and reduce the impacts of flash flooding.

- 9000 square feet of cool roofs were created with reflective paint, to lower indoor temperatures and electricity bills.

- 136 catch basins were adopted and 640 pounds of debris diverted from the sewer system

- 76 rain barrels were installed to capture and slow storm water that floods local streets and reuse non-potable water.

The NJEJA Climate Education Committee has developed a successful ongoing partnership with the Long Branch School District at the invitation of NJEJA Board Member Avery Grant, who is a long time member of the Long Branch Board of Education. During focus group meetings, NJEJA presented four units of the Leadership Training program to the Long Branch high school teachers and led a trip to the Ocean County Materials Recovery and Composting Facility.

The Community-led Climate Resiliency Subcommittee reviewed research conducted by the Lower Passaic Urban Waters Partnership on the distribution of federal funds post Hurricane Sandy. The data is being reviewed with an equity lens to ascertain the extent to which EJ communities received funds and how EJ communities might achieve greater access to disaster relief in the future. The subcommittee proposes to produce a template for community-led mitigation and adaptation planning.

Energy Policy

Definition of Clean Energy

The definition of clean energy should include only solar power, wind power and small hydro projects. NJEJA has consistently argued against labeling nuclear power, incineration, and natural gas as clean energy.

Nuclear Energy should not be considered clean energy due to the highly toxic waste it produces. There are also safety and cost issues associated with nuclear power that could make its utilization problematic.

Incineration, including that of biomass, should be rejected as clean energy at least partly due to the air pollution produced when it is employed.

Similarly, natural gas power plants can emit a significant amount of health harming local air pollution. The point and method of extraction of natural gas, especially if fracking is used, is also a source of concern because of potential damage it could cause to any community located where the natural gas is being removed from the earth.

The work above is referenced from previous NJEJA documents. For more details and information click here.

Community energy planning is a process conceptualized by the Center for Earth, Energy and

Democracy in Minneapolis that would involve community residents, community organizations, and EJ organizations in decisions about energy production and consumption in their particular community. Participation in energy planning is often restricted to energy professionals and government employees. Residents, EJ organizations and community organizations often don’t have input into energy decisions made about their own communities.

Perhaps the most important aspect of community energy planning is ensuring there is input from community residents, community groups and EJ groups into key decisions about both energy production and consumption in their community.

One of these key decisions is where energy efforts should be focused in the community. The NJ Energy Master Plan did capture this idea when it stated that the community must be involved in identifying energy needs. However, much is still left unsaid about the planning process. For example, a needs assessment should be performed in a “bottom up” manner with extensive community involvement.

If these needs include energy infrastructure such as solar power then the community should play a critical role in deciding where that infrastructure is located and which co-benefits derived from that infrastructure should be emphasized. Possible co-benefits are economic opportunities that include jobs and entrepreneurship; educational opportunities that could include links to the local school system and research; and opportunities to participate in ownership of the infrastructure.

To facilitate this type of planning there needs to be governmental grants that support community energy planning not only on a municipal level but, perhaps more importantly, also on a community level and that contain incentives for the involvement of local citizens and community groups.

If community energy planning is performed widely and in the correct manner it could play an important role in ensuring that EJ communities have access to energy efficiency and renewable energy.

The work above is referenced from previous NJEJA documents. For more details and information click here

Urban Community Energy Utilities is an idea NJEJA has introduced that could be helpful in implementing a coherent urban energy strategy that, among other things, makes EE and RE accessible to EJ communities.

These utilities would be non-profit organizations that gather capital and make it accessible to urban communities by investing in local EE and RE projects, including energy infrastructure, training programs and educational workshops. The utilities could be partly funded by the state’s social benefits charge and, or, the clean energy fund.

The utilities could provide multiple opportunities for EJ community residents, community groups and EJ groups to be involved in energy issues on a community level. They could also conduct energy education and when combined with community energy planning could help make the vision of New Jersey urban areas as centers of energy expertise and innovation a reality.

NJEJA was introduced to the idea by the Center for Earth, Energy and Democracy.

The work above is referenced from previous NJEJA documents. For more details and information click here

If affirmative actions are not taken to ensure that EE and RE are accessible to EJ communities, NJEJA fears they will be utilized primarily and disproportionately in White middle class and upper-class communities, and not used sufficiently in communities Of Color and low-income communities.

If this does occur it would be an example of climate change and energy policy perpetuating and very likely exacerbating current societal racial and class based inequalities.

One mechanism for ensuring this accessibility, is a set aside for EJ communities in any EE or RE program developed by the state. NJEJA recommends that at least 24% of customers served by the program should be of middle or low-income with at least 10.4% being low-income. This is the lowest the set aside should be and NJEJA would, of course, strongly support a higher level set aside.

NJEJA recommends that at least one–third of the clean energy fund in NJ be dedicated to EE and RE programs in EJ communities. Although NJEJA has not seen any hard data on the topic, we strongly suspect that the amount of funds contributed to the clean energy fund by EJ community residents through the societal benefits charge is greater than the amount of funds or value of services returned to those communities through energy programs.

The work above is referenced from previous NJEJA documents. For more details and information click here

EE and RE projects should be implemented in a manner that maximizes co-benefits to communities. One of the primary co-benefits is the generation of economic opportunities that include ownership of RE infrastructure, jobs, research opportunities and entrepreneurship opportunities.

Another co-benefit could be educational opportunities. NJEJA envisions a time when New Jersey cities will become known nation-wide for linking their public schools to the energy sector and producing young energy experts. Implementing EE and RE projects in a manner that maximizes these types of opportunities could help make urban areas in New Jersey centers of energy innovation.

Consulting community residents during a community energy planning process might be the best way to determine how to implement these projects so they will yield these valuable economic and educational opportunities.

The work above is referenced from previous NJEJA documents. For more details and information click here.

State agencies with authority to oversee the regulated utilities, must also take steps that allow and promote the participation of EJ community residents, EJ organizations and community organizations in their stakeholder processes.

Public participation can be particularly difficult for residents in EJ communities, in part due to a variety of social vulnerabilities they face. Similarly, EJ and community organizations frequently have difficulty engaging in governmental public processes due to a lack of human and financial resources.

NJEJA recommends the following to ensure a more meaningful participatory process for EJ communities and organizations:

- hold meetings in EJ communities;

- hold meetings at times that make it easier for community residents to attend;

- advertise meetings specifically to EJ communities as well as the general public;

- invite EJ and community organizations that operate in the local area where the meeting is being held;

- consider contacting the local EJ and community groups to seek their help in crafting an agenda for the meeting;

- ask the local EJ and community groups for advice on the best ways to engage community residents and other community organizations.

These suggestions do not form the universe of ideas with respect to effective community engagement but they should be, at the very least, a good start. Another critical aspect of the participatory process is that EJ community and organizational stakeholders should have a real opportunity to affect the outcomes produced by the process. At the conclusion of the process, if community participants feel they never really had a chance to affect the decisions this could lead to bitterness on the part of the community and a refusal to participate in future processes. Public Utility Agencies must be willing to allow community input to impact their decisions.

The work above is referenced from previous NJEJA documents. For more details and information click here

– button to 2018 Comments

NJEJA urges that policies for Green Energy Jobs focus, or specialize in, training residents of low-income or Of Color communities by:

- Supporting effective existing clean energy job training programs that focus on EJ communities and to consider developing new programs of this type in areas of the state that lack them. These communities may have unique challenges that should be addressed during a job training program.

- Supporting existing programs and creating new programs that include, as part of their mission, addressing challenges in EJ communities

- Support existing programs, or create new ones, that train and educate EJ community residents on how to take advantage of entrepreneurship, design and research opportunities in the energy field.

The work above is referenced from previous NJEJA documents. For more details and information click here

An important idea whose development and implementation are long overdue but badly needed, is that equity and justice should be incorporated into the operation of the Grid. Currently, as far as we understand its operation, equity and EJ concerns are not taken into account by the Grid in NJ.

From an EJ perspective, this is an obvious problem since electricity generating power plants contribute significantly to local air pollution and are often located in or near New Jersey EJ communities.

Modernization of the Grid presents an important opportunity to integrate equity into its operation and to establish New Jersey as a leader in equity and energy policy.

Similarly, equity and EJ should also be incorporated into the Integrated Energy Plan (IEP). IEP modeling should include equity as a major goal to be achieved and also as a constraint to other goals. Incorporating equity and EJ into this modeling would, of course, require extensive consultation with the EJ community and EJ energy experts.

The work above is referenced from previous NJEJA documents. For more details and information click here

As Governor Murphy rejoined the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, committed to building 3,500 megawatts of offshore wind by 2030, and initiated a revision of the state Energy Master Plan, NJEJA worked with other clean energy, climate resilience, and just transportation advocates to produce equitable policy development and implementation. Consistent with our energy justice work to elevate the decision-making of environmental justice communities, NJEJA partnered with the Energy Foundation to: co-chair its Health and Equity Committee; participate in community solar pilot(s); draft energy policy climate and equity considerations; address barriers to energy efficiency and renewable energy, and propose targeted emission reductions from transportation sector.

NJEJA lent an environmental justice perspective to the proposed New Jersey Energy Master Plan by testifying at the Board of Public Utilities (BPU) hearings and submitting formal comments. At the Camden hearing, NJEJA Executive Director, Laureen Boles, emphasized development and implementation of the Energy Master Plan could be the first test of Governor Murphy’s Environmental Justice Executive Order, which mandates environmental justice as a goal of state policies.

As Governor Murphy rejoined the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, committed to building 3,500 megawatts of offshore wind by 2030, and initiated a revision of the state Energy Master Plan, NJEJA worked with other clean energy, climate resilience, and just transportation advocates to produce equitable policy development and implementation. Consistent with our energy justice work to elevate the decision-making of environmental justice communities, NJEJA partnered with the Energy Foundation to: co-chair its Health and Equity Committee; participate in community solar pilot(s); draft energy policy climate and equity considerations; address barriers to energy efficiency and renewable energy, and propose targeted emission reductions from transportation sector.

The Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy Subcommittee refined its campaign work-plan intended to improve access for environmental justice communities to energy efficiency and renewable energy. The subcommittee proposes to map the energy needs of low income communities in several New Jersey cities, then advise New Jersey urban municipalities on which federal energy efficiency and renewable energy programs would best meet community needs, all in partnership with the Urban Mayors Association of the John S. Watson Institute for Public Policy at Thomas Edison State University.

NJEJA lent an environmental justice perspective to the proposed New Jersey Energy Master Plan by testifying at the Board of Public Utilities (BPU) hearings and submitting formal comments. At the Camden hearing, NJEJA Executive Director, Laureen Boles, emphasized development and implementation of the Energy Master Plan could be the first test of Governor Murphy’s Environmental Justice Executive Order, which mandates environmental justice as a goal of state policies.

Supporting EJ Communities

This course will examine the roots of the Environmental Justice Movement, including its underpinnings in the Civil Rights Movement, and the interchange of racism and economic inequity in the strive for this socioeconomic goal. Students will have the opportunity to engage in an interactive exercise that dramatizes the basic problems that the EJ Movement addresses.

This course is an introduction to community organizing, with a focus on building local opposition to polluting industries in Environmental Justice communities. Students will learn the Elements of Organizing, and how to apply them is real world scenarios.

This course is an introduction to the Ironbound neighborhood of Newark, New Jersey, the site of an unsustainable burden of legacy and ongoing environmental pollution. This 4‐mile square neighborhood contains numerous waste‐related facilities, international trade and transport hubs, and the nation’s biggest Superfund site. There will be ample time for questions and reflections as we view prime examples of environmental justice issues and learn about the community’s history of fighting back.

This course is an introduction to the unspoken assumptions people use to justify not treating trash as a valuable natural resource. Students will also be introduced to the use of a waste audit as a tool for creating better recycling systems and moving towards zero waste.

This course is an introduction to the concept of Food Justice and why it matters to EJ communities like Newark. Students will learn Food Justice Principles and how activists from all over the country are applying them to reshape the local food landscape for the most vulnerable populations.

This course is an introduction to particulate matter air pollution. Particulate matter will be defined and its composition, sources and health effects will be discussed. Emissions reduction policies developed by the New Jersey Environmental Justice Alliance and allies will also be discussed.

This course will examine the roots of the Environmental Justice Movement, including its underpinnings in the Civil Rights Movement, and the interchange of racism and economic inequity in the strive for this socioeconomic goal. Students will have the opportunity to engage in an interactive exercise that dramatizes the basic problems that the EJ Movement addresses.

This course is an introduction to the issue of cumulative impacts will be defined and policies developed by the New Jersey Environmental Justice Alliance and allies to address the issue are presented.

A Roadmap to the Environmental, Economic & Equitable Future of Newark. This course is an introduction to sustainable living in a green economy. Students will become familiar with the contents of the plan, learn how to become an active participant, and contribute to the plan as it evolves.

This course affords the participants the opportunity to map community assets and liabilities. Students will ground truth data from city, state and federal databases and add their perspective of community assets and liabilities, thus providing a local lens to community characteristics.

This course affords the participants the opportunity to monitor the air quality in the vicinity of community’s assets and liabilities. Students will collect field data and make comparisons to city, state and federal databases.

In this course students will analyze the data collected in the course, discuss the findings, and draw individual conclusions. Students will also provide feedback on the environmental justice leadership training course and make recommendations for improvements.

Rutgers Future Scholars is a pre-collegiate academic enrichment program, and tuition-free pathway to higher education, offered to select high school students in the vicinity of Rutgers’ campuses. NJEJA conducts trainings with Rutgers Future Scholars, introducing students in 8th and 9th grade to concepts and topics on environmental justice. Participants in the program have been from the cities of Rahway, New Brunswick, Piscataway, and Highland Park.

Rutgers Future Scholars is a pre-collegiate academic enrichment program, and tuition-free pathway to higher education, offered to select high school students in the vicinity of Rutgers’ campuses. NJEJA conducts trainings with Rutgers Future Scholars, introducing students in 8th and 9th grade to concepts and topics on environmental justice. Participants in the program have been from the cities of Rahway, New Brunswick, Piscataway, and Highland Park.

Through interactive exercises, students examine the roots of EJ, including its underpinnings in the Civil Rights Movement, and the interchange of racism and economic inequity in the strive for this socioeconomic goal.

This course is an introduction to the Elements of Organizing, with a focus on EJ issues. Students will learn how to apply the organizing elements in real world scenarios.

Students will tour a site with an unsustainable legacy of environmental pollution in order to view prime examples of environmental injustice and learn about strategies toward a healthier port.

Students will be introduced to trash as a valuable natural resource, and to a waste audit as a tool to create better recycling systems and moving towards zero waste.

This course is an introduction to the Food Justice Principles and how activists across the country are applying them to reshape the local food landscape for EJ communities.

This course is an introduction to particulate matter air pollution, its composition, sources, and health effects, as well as the emissions reduction policies developed by the NJ EJ Alliance.

This course is an introduction to climate change from an EJ perspective, including mitigation and adaptation policies, greenhouse gas co-pollutants, carbon trading, and EPA’s climate change rule (the Clean Power Plan).

This course is an introduction to the concept of cumulative impacts as well as the policies developed by the NJ EJ Alliance and its allies to address the issue.

This course is an introduction to sustainable living in a green economy. Students will become familiar with a sustainability plan and learn how to make applications in their lives.

A Student Perspective: Students map community characteristics, ground truth data from city, state and federal databases, and explain variations.

A Student Perspective: Students monitor air quality in the vicinity of community assets and liabilities, collect data and explain results.

Students will analyze environmental data, discuss findings, draw individual conclusions, and make recommendations for improvements to EJ training.

Students will analyze environmental data, discuss findings, draw individual conclusions, and make recommendations for improvements to EJ training.