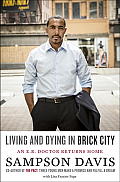

New Book — Living and Dying in Brick City: An E.R. Doctor Returns Home

by Sampson Davis

It was just before 7:00 A.M. on July 1, 1999, my first full day on the job. Jay-Z blared from the stereo as I steered my old Honda Accord past the White Castle burger joint, toward Newark Beth Israel Medical Center. The neighborhood — a mix of boarded up buildings, dingy brick storefronts, beauty supply stores, and fast-food restaurants — rolled by like a video. Before long, the July heat would draw residents out of their homes to play checkers and cards, children in swimsuits would be dashing through open fire hydrants, and sweaty boys would be swooshing basketballs through naked rims on concrete courts. This was Brick City, my city. I knew its rhythms, and I’d seen its dark side up close. Even at this time of morning, I could see glimpses of it: the homeless old man sleeping next to a junk-filled grocery cart and a couple of half-naked women still strutting the blocks from the night before. The dope boys and other hustlers would be out later, too, stirring up all kinds of trouble — trouble that at times has given my hometown a reputation as one of the most dangerous cities in America. I used to be one of those confused boys, a kid with potential I didn’t even know existed inside of me, a kid who wanted better but for the longest time couldn’t crystallize in my mind what that might look like, let alone how to get it. That seemed like a lifetime ago.

I slowed down to enter the zone around the hospital, one of New Jersey’s premier medical institutions. Its sprawling redbrick buildings towered over both sides of Lyons Avenue and consumed practically the entire block. I turned into the five-story parking garage across from the hospital’s main entrance and smiled at the funny ways of fate. Here I was, a doctor now, pulling in to the same hospital where eight years earlier, one summer evening after my senior year in high school, I’d spent practically the entire night parked outside the ambulance entrance with two carloads of my friends. We’d rushed to the hospital with a friend who was convinced that the marijuana he’d just smoked was about to kill him. But when we got there, we were too scared to go inside for help and too high to know better. We’d been drinking that hot summer night, and my friend had decided to try some weed for the first time. Then the buzz he’d anticipated didn’t happen fast enough.

“Aww, Marshall, this ain’t nothing,” he’d said, calling me the middle name used by my family and old friends. “I can’t get high.” He kept smoking and smoking. Then sweat started popping out all over his face, and his heart rate sped up. “Feels like it’s about to beat outta my chest,” he said, panting and pleading with us not to let him die.

We jumped in our cars and drove to Beth. Between cracking up with laughter and feeling scared out of our minds, we debated the consequences of going inside. Like me, my incapacitated friend was one of the few in our group headed to college. What would happen if the E.R. doctors discovered that he was not really about to die, but instead high? Would this go on some kind of record and get him kicked out of college before he even started?

“It’s just the weed, man. It’s just the weed,” we told him repeatedly, trying to calm his fear that he was about to meet his maker. We came up with a plan: We’d sit with him in the car and pace with him on the street to give the weed time to wear off, but we’d stay parked outside the emergency room, in case. If our friend looked like he was about to pass out, we would only have to rush a few steps inside. My mom always said God looks out for babies and fools, and the good Lord must have been looking out for us that night. The weed wore off without my friend having a heart attack, and we got back in our cars and drove home. Who could have guessed then that old Marshall someday would have his own parking space in the doctors’ lot at Beth?

I steered into one of the reserved spots on the first floor of the garage and stepped out of my car. I draped my stethoscope around my neck, pulled on my white lab coat, smoothed it back and front, then ran my hand over the black thread embroidered across the top left side: Sampson M. Davis, M.D., Emergency Medicine.

I liked the feel of it.

Through some miracle, I had not only survived these merciless streets but also ended up as a doctor at the same hospital where I took my first breath. Fresh out of medical school, I was now on the other side of the desperation and despair: the healing side. From this unique vantage point, I would come to see the community where I was raised and the high price of poverty in a whole new way. I would see lives that might have been saved if the industrious young men landing in my emergency room full of bullet holes had learned and believed that education offered a better alternative. I would see young women giving up their power and entrusting their health to unworthy men — and dying because of it. I would see health issues out of control — obesity, diabetes, heart disease, stroke — and behaviors that unwittingly perpetuated a disproportionate rate of death. And I would see myself.

There are plenty of books by doctors who have shared their experiences working in a hospital or their expertise on various health issues, but few have drawn attention to the health crisis in our inner cities. The violence, the despair, the poverty, the hopelessness — they all have been examined as societal, social, and cultural issues; yet there are inextricable medical issues as well. These are the physical and mental health conditions that play out night after night in emergency rooms across the country and sap communities of their strength and vitality. After more than a decade working on the front line of healthcare in my own beleaguered community, I have seen remarkable resilience, but I have also witnessed far too many tragedies. That is why I am sharing these stories, along with information that can mean the difference between illness and health, between life and death.

Some names and physical descriptions have been changed to protect the identities of those who have suffered and, in some cases, the families they left behind. But every story is real. My hope is that this book will inspire change. That it will open eyes wider to the serious health problems facing a too- often overlooked population. That it will encourage political and community leaders, medical professionals, and others with brilliant minds, creative ideas, and positions of influence to make a difference on this front. But most of all I hope that men and women living in the conditions described here will see themselves and their loved ones in these stories, turn away from self- destructive behaviors, and seek appropriate medical help.

For me, emergency medicine has been a calling, a vocation connected to my higher purpose. Ultimately, this book is part of that, another way to do what I got into medicine to do in the first place: help save lives.

Excerpted from Living and Dying in Brick City: An E.R. Doctor Returns Home by Sampson Davis. Copyright 2013 by Sampson Davis. Excerpted by permission of Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of Random House.

http://www.npr.org/books/titles/171472471/living-and-dying-in-brick-city-an-e-r-doctor-returns-home#excerpt

Comments on NEPA Rollbacks Affecting EJ Communities