Attorney General Eric Holder recently described how he had been stopped twice, and his car searched, for no apparent reason on the New Jersey Turnpike. Here is the relevant section of his talk, delivered July 16, 2013 to the NAACP Convention:

[snip]

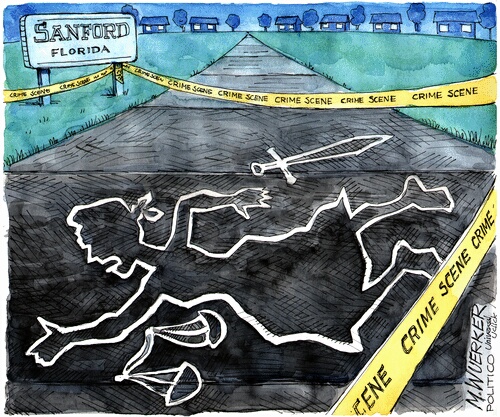

"Even as this convention proceeds, we are all mindful of the tragic and unnecessary shooting death of Trayvon Martin last year – in Sanford, just a short distance from here – and the state trial that reached its conclusion on Saturday evening. Today, I’d like to join President Obama in urging all Americans to recognize that – as he said – we are a nation of laws, and the jury has spoken. I know the NAACP and its members are deeply, and rightly, concerned about this case – as passionate civil rights leaders, as engaged citizens, and – most of all – as parents. This afternoon, I want to assure you of two things: I am concerned about this case and as we confirmed last spring, the Justice Department has an open investigation into it. While that inquiry is ongoing, I can promise that the Department of Justice will consider all available information before determining what action to take.

"Independent of the legal determination that will be made, I believe this tragedy provides yet another opportunity for our nation to speak honestly – and openly – about the complicated and emotionally-charged issues that this case has raised.

"Years ago, some of these same issues drove my father to sit down with me to have a conversation – which is no doubt familiar to many of you – about how as a young black man I should interact with the police, what to say, and how to conduct myself if I was ever stopped or confronted in a way I thought was unwarranted. I’m sure my father felt certain – at the time – that my parents’ generation would be the last that had to worry about such things for their children.

"Since those days, our country has indeed changed for the better. The fact that I stand before you as the 82nd Attorney General of the United States, serving in the Administration of our first African American President, proves that. Yet, for all the progress we’ve seen, recent events demonstrate that we still have much more work to do – and much further to go. The news of Trayvon Martin’s death last year, and the discussions that have taken place since then, reminded me of my father’s words so many years ago. And they brought me back to a number of experiences I had as a young man – when I was pulled over twice and my car searched on the New Jersey Turnpike when I’m sure I wasn’t speeding, or when I was stopped by a police officer while simply running to a catch a movie, at night in Georgetown, in Washington, D.C. I was at the time of that last incident a federal prosecutor.

"Trayvon’s death last spring caused me to sit down to have a conversation with my own 15 year old son, like my dad did with me. This was a father-son tradition I hoped would not need to be handed down. But as a father who loves his son and who is more knowing in the ways of the world, I had to do this to protect my boy. I am his father and it is my responsibility, not to burden him with the baggage of eras long gone, but to make him aware of the world he must still confront. This is a sad reality in a nation that is changing for the better in so many ways."

[snip]

You can read the full text of Mr. Holder’s July 16, 2013 speech here: http://goo.gl/pUmKl

Florida Case Spurs Painful Talks Between Black Parents and Their Children

New York Times, July 17, 2013

By John Eligon

University City, Mo. — Tracey Wolff never had a problem with her 19-year-old son’s individualism: his “crazy” hair and unshaven face. But this week, his look suddenly seemed more worrying.

When she thinks of Trayvon Martin and his cropped hair and smooth face, Ms. Wolff says, she wonders, “If that can happen to the clean-cut kid who looks like a good student, then what’s going to happen to my son, who dresses sloppy?” She is considering talking to him about reconsidering his look.

“I don’t want to tell him how to dress,” she added. “He’s a grown man; do what you want to do, but keep in mind these are the things going on.”

On cable news programs and in protests around the country, the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of Mr. Martin, an unarmed black teenager, in Sanford, Fla., has been fodder for an intellectual discussion on race and justice. But for many black residents, the verdict has spawned conversations far more personal and raw: discussions of sad pragmatism between parents and their children.

The intimacy of the Martin case for black Americans was drawn into the spotlight this week when Attorney General Eric H. Holder Jr. said during an N.A.A.C.P. convention that he had had a conversation with his 15-year-old son about the case, much the way his father once counseled him about how to interact with the police.

Similar conversations are being held across the country, including here in this racially mixed St. Louis suburb.

On Wednesday afternoon, people of various races sat side by side in the cafes, restaurants and boutiques that line the town’s main road, blocks from Washington University. Longtime residents said racial tensions were not historically a problem in University City, where just over 50 percent of the residents are white and 41 percent are black. But some said the Martin case had rattled their sense of security.

Missouri, like many states, allows residents to carry concealed weapons with a permit. It also allows people to use deadly force in defense of their homes or vehicles without a duty to retreat. On Wednesday, fliers depicting a hoodie, the type of sweatshirt Mr. Martin wore on the night of his death, were taped to poles along the main road. They read, “No more dead youth no matter who’s holding the gun. One love.”

“They’re still showing racism is powerful and still alive,” Ashley Gaither, 22, said, referring to the acquittal of Mr. Zimmerman, who had said he was acting in self-defense. Speaking of her 3-year-old son, Isaiah, Ms. Gaither added: “It’s just sad. It’s already going to be hard for him being a young black male growing up.”

Her fiancé, Eddie Kirkwood, 24, said of their son, “I don’t want to let him walk to the store by himself, especially after that.”

The whole situation, added Ms. Gaither, a nurse’s assistant, “would just make me skeptical about what crowd of white people I put him around.”

Lesley Grice, 35, who was visiting a friend here but lives in Kirkwood, a St. Louis suburb that has a history of rocky race relations, said she had asked her 18-year-old son to stop wearing hoodies, a request that did not go over so well. “He’s like, ‘That’s what I like to wear,’ ” she said.

Ms. Grice, a housekeeper, said she had also told her son that when he was talking to adults, to keep his hands in place so it was clear that he was not reaching for anything.

Christian Hayes, 24, said he did not know what he would tell his 7-month-old twin sons about the Martin case when they were older. For now, he described a sense of being trapped in his own neighborhood. If someone were following him, he said, “I’m not going to run; I’m going to ask him what he’s following me for.” But, he added, “It just makes me feel like you can’t do nothing or go nowhere.”

As he walked down the street in rubber sandals on Wednesday afternoon, Rashaun Cohen, 17, said he carried himself differently since the shooting. His gray sweat shorts hung well past his knees, but he said he tended not to let his pants sag anymore. His mother also offered some advice, he said.

“Just, like, don’t walk into any neighborhood like I’m hard,” he said. “Just always be respectful and humble.”

Mr. Cohen, a high school junior, said Mr. Zimmerman’s acquittal was troubling because he believed that “it’s giving people the O.K. to do that.”

Shannon Merritt, 35, said the Martin case provided a larger teachable moment for her 19-year-old brother and 18-year-old son. One of the first things she did after the verdict, she said, was to tell her brother: “Please stay in school; just work, try not to be a statistic.”

Her daughter cried, Ms. Merritt said. Her daughter also became curious about the historic struggles blacks have faced in this country. They researched that topic and the uphill battle women have waged for rights like the freedom to vote.

“I’m going to help with the movement,” Ms. Merritt said her daughter told her.

© 2013 The New York Times

Racial Disparities in Life Spans Narrow, but Persist

New York Times, July 18, 2013

By Sabrina Tavernise

The gap in life expectancy between black and white Americans is at its narrowest since the federal government started systematically tracking it in the 1930s, but a difference of nearly four years remains, and federal researchers have detailed why in a new report.

They found that higher rates of death from heart disease, cancer, homicide, diabetes and infant mortality accounted for more than half the black disadvantage in 2010, according to the report by the National Center for Health Statistics, the federal agency that tracks vital statistics for the United States.

Still, blacks have made notable gains in life expectancy in recent decades that demographers say reflect improvements in medical treatment as well as in the socioeconomic position of blacks in America. Life expectancy at birth was up by 17 percent since 1970, far higher than the 11 percent increase for whites over the same period.

Demographers credit declining rates of AIDS and homicide, which ravaged black neighborhoods in many American cities in the 1980s and ’90s, as well as reduced death rates from heart disease. Blacks, who have higher rates of heart disease, have benefited disproportionately from improved treatment of it, said Samuel Preston, a demographer and sociologist at the University of Pennsylvania. But there is still a lot of room for improvement, especially to prevent heart disease in blacks, experts said.

Life expectancy for blacks rose to 75 years in 2010, up from 64 years in 1970. For whites, it rose to 79 years from 72 years in the same period. In 1930, life expectancy stood at 48 for blacks and at 60 for whites.

Higher infant mortality among blacks also contributes to the gap, but less than it used to. The infant mortality rate for blacks fell by 16 percent from 2005 to 2011, compared with a 12 percent drop for whites, said Kenneth M. Johnson, a demographer at the University of New Hampshire.

Heart disease was the single biggest drag on black life expectancy, accounting for a full year of the 3.8-year difference between whites and blacks. The second-biggest factor was cancer, accounting for about eight months of the difference.

The report’s lead author, Kenneth D. Kochanek, said that 1994 was the last time his office published a report that focused on what was driving life expectancy disparities. At that time, researchers were exploring a surprising decline in life expectancy for blacks between 1984 and 1989 that was driven in part by AIDS and homicide among black men, and AIDS and diabetes among black women.

The new report analyzed data from 2010. Preliminary statistics for 2011 show that the gap has continued to narrow to 3.7 years.

Whites have suffered a setback in a category known as unintentional injuries, which includes the surge in prescription drug overdoses that has disproportionately affected whites since the 1990s.

Blacks also had lower death rates than whites from suicide, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases, and respiratory diseases like emphysema, as well as chronic liver disease.

Sam Harper, an assistant professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at McGill University in Montreal who has done extensive work on disparities in life expectancy, said some drivers of black disadvantage are preventable, like heart disease. Public health efforts should focus on reducing risk factors like smoking, poor diet and hypertension, he said.

Policy makers should also make sure that blacks are benefiting from improvements in medical treatments for cancer and heart disease, he said. “Redoubling our efforts on these two diseases would go a long way toward reducing the black-white life expectancy gap further.”

© 2013 The New York Times

NJ’s Poor Struggle to Stave Off Hunger with Federal Food Aid

NJ Spotlight, July 17, 2013

[The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program pays less than $1.50 a meal, but some critics contend that spending is out of control.]

By Hank Kalet

As Congress debates the best way to pass a federal farm bill, advocates for New Jersey’s food-aid recipients are concerned that efforts to slash funding for nutrition programs could overburden family budgets at a time when the state’s economy remains fragile and its unemployment rate remains above the national average.

Those receiving food aid say they will need to make tough choices if money from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program is cut — choices made all the more difficult because most are already buying only what they consider to be the necessities.

Critics of food-aid programs like SNAP, however, say reductions are required to rein in an out-of-control entitlement and that eligibility rules need to be changed to protect those truly in need.

The farm bill, known officially as the Federal Agriculture Reform and Risk Management Act, is the chief funding mechanism for the federal Department of Agriculture. It funds grain and milk price subsidies, food inspection, and most of the nation’s nutrition and emergency food programs for families and low-income seniors.

Members of the Senate and House from both parties have been pushing for reforms that would update price supports and food aid but have been unable to reach an agreement. A Senate bill that included a 10-year, $4 billion reduction in SNAP passed, while the House bill, which called for $20.5 billion to be sliced off over a decade, was defeated 234-195 when members of both parties balked at the SNAP cuts — Democrats because they were too large and Republicans because they were not large enough.

On Thursday, the House approved a version of the bill covering farm programs but not food aid. The vote was 216-208, with New Jersey Republicans Rodney Frelinghuysen, Scott Garrett, Leonard Lance, Jon Runyan, and Chris Smith voting yes and Republican Frank LoBiondo joining all six New Jersey Democrats in voting no.

A food-stamp bill is expected later in the year, though there is no timetable for action, staffers say. Food programs traditionally have been included in the farm bill to win urban votes for what have been viewed as rural spending and have not been voted on as separate bills for about 40 years.

A temporary benefit boost enacted as part of the 2009 Recovery Act will expire on November 1, which will decrease benefits for most SNAP recipients by $20 to $25 a month, according to estimates from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in Washington, D.C.

Benefits and Beneficiaries

Nationally, about 50 million people receive SNAP benefits, some 40 percent of whom are children and about 8 percent seniors.

In April, 859,353 New Jersey residents received SNAP benefits, nearly one out of every 10 people who live in the state. Almost four in 10 of those receiving SNAP live in Essex, Hudson, and Passaic counties. The number of SNAP participants has more than doubled since April 2008, just before the national financial collapse, with growth concentrated during the height of the crisis in 2009-2011 and slowing the past two years.

“[SNAP participation] is about as high as it has ever been,” said Diane Riley, director of advocacy for the Community Food Bank of New Jersey, the state’s largest food bank. "You have to remember that New Jersey still has quite a high unemployment rate, higher than the national average. You will see less SNAP participation as a natural effect of a better economy.”

Shawn Sheekey, director of the Camden County Board of Social Services, said agencies are still dealing with the increase in clients – and that the jump in numbers has come from a new segment of the population.

“It has doubled in size, but what is amazing to me is . . . we obviously deal with the inner-city poor, but what is so different about this whole Great Recession is seeing families that were traditionally not on any kind of assistance come in,” he said. “Families where the mom and dad were working at $90,000 jobs and the company downsizes.

“We are seeing more of that type of activity,” he added. “People need the benefits to keep the family fed.“

The growth in SNAP participation, which tracks closely with the growth in unemployment nationally and in the state, shows how important federal nutrition programs are, advocates say. The programs are needed to prevent hunger and to ensure that hundreds of thousands of Americans, including a record number of New Jersey residents, can continue to put food on their tables.

Ray Castro, senior policy analyst at the liberal New Jersey Policy Perspective, called SNAP benefits necessary for New Jersey’s low-income families.

“Without the supplementary programs for the childless and for families, it is hard to see how they would survive in New Jersey,” he said.

The November cuts, he said, would reduce the amount provided per meal under SNAP from $1.48 to $1.40.

“That is not much to live on,” he said. “Any additional cut beyond that will be a major problem, particularly in New Jersey because our economy has not recovered as quickly as others have.”

Riley said food banks and soup kitchens will not be “able to pick up the slack."

“We are supposed to be for emergency and not this kind of support,” she said.

Too Generous

But critics of the program say that food aid is too generous and that better controls are necessary to ensure that the programs only serve those who need help the most. Groups like the conservative Heritage Foundation have been critical of the program for fostering what it calls a dependency culture.

Rachel Sheffield, a research assistant at the foundation, said on the organization’s blog that “food stamp spending should be rolled back to pre-recession levels when the employment rate recovers” in an effort to “get spending under control.” The program, she added, needs to “be restructured to promote work instead of discourage it.”

“Smart cost reforms accompanied by efforts to promote self-sufficiency through work would take food stamps off its reckless spending spree and put it on a road to fiscal responsibility,” she said.

Runyan, a South Jersey Republican, was one of two New Jersey Congressmen — Frelinghuysen was the other — to vote in favor of the farm bill in June. He called its failure “another example of Washington making the perfect the enemy of the good.”

The legislation passed the House Agriculture Committee with bipartisan support and would have “included over $40 billion in savings to the taxpayer,” he said in an email. The $20.5 billion in “reforms to the SNAP program” would have been “the first major changes since the welfare reforms of the 1990s,” he said.

“I have yet to see a federal program that doesn’t at some point need to be updated, both as a means of protecting the taxpayer, and ensuring these programs can be sustained, and are meeting their intended purpose,” he said.

U.S. Rep. Donald Payne Jr., who represents Essex and parts of Hudson and Union counties, said in a press release that SNAP was a “vital program that helps families that are struggling to make ends meet” and that the proposed House cuts were “completely unconscionable.”

“In the best nation on Earth, it is astonishing that millions of people, many of whom are children, still go hungry,” he said. “As leaders we have a responsibility to protect our children and promote the well-being of the most vulnerable.”

Payne added in a second release Thursday that “separating supplemental nutrition assistance from the Farm Bill went against a four-decade precedent.” Congress, he said, has “completely turned their back on starving children and the most underserved in this country.”

Fellow Democrat Albio Sires, who represents parts of Essex, Hudson, Union, and Middlesex counties, called the passage of a Farm Bill “critical” to the nation’s food supply. But Sires voted against the bill, he said in a press release, because he could not “support measures that achieve that goal by slashing nutrition assistance to our nation’s most vulnerable citizens.”

Both Payne and Sires — along with Democrats Rob Andrews and Bill Pascrell and Republicans Chris Smith and Frank LoBiondo — voted for an amendment that would have restored full funding for SNAP in the bill. The amendment was defeated before the June vote.

A separate amendment that would have increased the SNAP cuts by nearly $11 billion to $31 billion over 10 years was also defeated. Republican Scott Garrett, who represents Warren and parts of Sussex, Passaic, and Bergen counties, was the only New Jersey Congressman to support the amendment.

Forced Reductions

Studies by liberal groups say that the House bill would have forced as many as 2 million people off SNAP, nearly 60,000 of them in New Jersey. The Senate bill cuts $4.1 billion over 10 years by imposing new eligibility requirements tied to energy assistance — the so-called heat-and-eat programs — and making other cuts. Those state-level programs allow low-income people to deduct payments they receive from the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program from their overall income when calculating their SNAP benefits.

SNAP also is facing more direct cuts, as are other nutrition programs, like Meals on Wheels, Senior Congregant Care, and a federal farmer’s market program that enables low-income families and individuals to shop cheaply at local produce stands.

Jim Sigurdson, executive director of Community Services, Inc. of Ocean County said the larger senior programs like his could be affected if the nutrition programs are cut. If that happens, he said, it would have a geometric impact.

Seniors who rely on agencies like Community Services for some of their primary meals and who rely on the federal farmer’s market program would need to plug those gaps with what is left of their SNAP benefit or their own resources.

“The fresh produce is significant for someone who is of low income,” Sigurdson said. “Oftentimes, there is a trade-off. You have to purchase things that are of less nutritional value because you have to have your belly full. Can of pasta costs a whole lot less and it has a longer shelf life.”

Senior congregant meals help seniors “stretch that food stamp budget,” he said, and “contributes to the overall health of these individuals and allows them to remain living in their own homes and their own communities. And it keeps them out of institutions that put a greater tax burden on the public.”

Riley said the eligibility and income changes being proposed by both houses will only further chip away at food programs that keep many above water. Under current rules, a family of four earning about $42,000 could be eligible for food aid; eligibility changes, however, would put the ceiling at about $23,000 for the same-size family, leaving a lot of families without assistance.

“Imagine living on [$42,000] in New Jersey and not needing help,” she said. ”To take it back to $23,000, that is going to send more people into a desperate situation.”

Breaking the Budget

Carolyn Biondi, executive director of the Crisis Ministry of Princeton and Trenton, said that SNAP benefits affect the entire family budget. Recipients, she said, “rely on food stamps to meet food needs, but also to offset those costs so they can pay their other bills.”

Castro agreed. He said that about 80 percent of food-aid money is spent within the first two weeks of the month, which leaves families in a bind.

“They have one family budget to live on and, if they have less money for food in food stamps, that means they don’t pay their rent that day to make up the difference,” he said. “That is the choice they have to make: whether they want to become homeless or go hungry.”

Mirian Contreras, a single mother of three in Trenton, has been receiving food aid through SNAP for three years and still has to visit food pantries periodically to ensure she has enough food in the house. Her SNAP benefit, she said through a translator, is $429 a month. She works full time earning about $1,000 a month after taxes, but pays $650 for a small, one-bedroom apartment next to a liquor store in the city. She doesn’t have a phone and uses state-backed charity care when she needs to see the doctor.

SNAP allows her to buy the basics — bottled water, meat, rice, milk, juices, and occasionally fresh fruit. She generally shops at one of the small food stores in the city because she lacks transportation, but they are more expensive than the larger supermarkets in neighboring Ewing or Hamilton.

She tries to put a little away each week “for emergencies,” though she generally has to “tap into that at the end of the month,” she said. She received about $2,500 from the Earned Income Tax Credit last year, she said, though most of that has been spent.

“If you take away food stamps or cut what I get, it would be much worse,” she said. “With $650 for rent and the check I get, it is not enough. Everything comes and goes so quickly.”

Judith Elboraa, of South Brunswick, says the SNAP program has allowed her to keep food on the table since being stricken with cancer several years ago. She works when she can, but she is limited in the kinds of jobs can do because of her health and a lack of stamina.

“I was working a full-time job in retail when I got cancer,” she said. “After that, I couldn’t go back to retail anymore, because it was too strenuous. Then I had to go on Medicaid, welfare, and SNAP because I couldn’t go back to work.”

She has worked sporadically since, though her wages have never been enough to maintain a household that includes her son and her elderly mother and regularly has to find ways to cut back on expenses.

“We’ve had to make a lot of cuts,” she said. “When I was working, I took my son out to eat now and then. We’ve cut back to necessities, cut out all the luxuries.”

And she coupon shops.

“I have to be more careful in checking the stores to see what is on sale,” she said. “Now, it is ‘don’t buy something until it goes on sale somewhere else.’ If I’m going to splurge and spend a little extra on a chicken that is not on sale, it is going to hurt us by middle of month, because we will have nothing left.”

Elihu Froomess, a senior citizen living in Brick Township, said his SNAP benefits — “somewhat less than $100 a month” — often do not last beyond the third week of the month. If they were cut, he said, the five days per month that he has to scrape by would be much longer, though he said he is lucky to qualify for various senior services.

“I’m very fortunate that because of the federal programs still intact I don’t have to make some of these choices, because my medical and healthcare are provided through federal and state programs,” he said.

Still, there are five days a month, “when I have to seriously consider what to do,” he said. “It is a mix of prayer and fasting or relying on others.”

I get to pick a fight if I don’t like the way you look…

Zimmerman: The Criminal Trial is a Privilege of Whiteness

Boston Review July 15, 2013

By Simon Waxman

At the rally for Trayvon Martin in Boston last night, one speaker earned a raucous applause for sneering at the jury that set George Zimmerman free on Saturday. Was that panel of six women, five of them white, the speaker asked, a jury of Martin’s peers? He chuckled and shook his head, and the 500 or so onlookers clapped, booed, and raised hands in agreement.

The impulse to blame the nearly all-white jury is understandable. American history is full of such juries rendering injustice. And there is no question that the result in the Zimmerman trial was injustice. The course of events is beyond doubt: Zimmerman, fearing for the security of his neighborhood with a young black man at large, pursued Trayvon Martin, got in a fight with him, and then shot Martin when his quarry got the better of him.

Thus it has now become an article of faith among many: had the skin tones been reversed, had George Zimmerman been black and Trayvon Martin white, Zimmerman would surely have been found guilty.

This speculation is impossible to test, but it’s probably wrong.

For one thing, the jury was not the source of the injustice. It made a rational decision based on Florida law and the facts it was allowed to consider. One would like to believe that in the speculative scenario, black George Zimmerman would have been subject to the same laws, trial rules, and deliberative process.

But, as long as we are engaged in speculation, we should consider the more likely and therefore more instructive scenario: had George Zimmerman been black, there would never have been a trial.

Had Zimmerman been black, he would have been arrested immediately and charged within days. Because Zimmerman is white — those who wish to suggest he is Latino and therefore the racial “overtones” of the case are exaggerated simply do not understand the difference between race and ethnicity or how race is constructed in America — he was detained for five hours and released without charge or further investigation. Only after six weeks of protests, mostly by black citizens, was he charged, after which he turned himself in.

Recall that in August 2012, Zimmerman claimed to be indigent. His supporters bought his high-priced legal team, but had Zimmerman been typical of the black men who pass through our criminal justice system, as opposed to a cause célèbre, he would have been declared indigent as requested and assigned an underpaid, overworked public defender. After having been charged, black Zimmerman would have languished in prison for several weeks before his lawyer came to him to discuss his case for a half hour or so. This would have precipitated a lengthy process of delays. The lawyer would have sought continuances in order to gain time to make a few more half-hour visits and prepare a case.

Black, indigent Zimmerman would have been denied bail, or else his bail would have been set so high that he would never have been able to pay it. While white Zimmerman prepared his trial from the comfort of his home, black Zimmerman would have spent more than a year behind bars awaiting trial.

But that trial would not have come. As time droned on, the prosecutor — herself overworked, underpaid, and hoping to clear cases by any possible means — would have offered a plea bargain. Black Zimmerman’s lawyer, with a hundred or more defendants vying for his attention, would have encouraged black Zimmerman to take the plea, accept a relatively lenient sentence, and serve his time.

And black Zimmerman would have taken that plea, as 95 percent of American defendants do. A black man knows that, faced with a second-degree murder charge in the killing of a white teenager, he doesn’t stand a chance at trial.

But because the real Zimmerman is white and had money for a private legal team dedicated exclusively to his needs, he was afforded the full range of advantages that a criminal trial can offer a defendant. He was able, for instance, to benefit from the rules of exclusion relevant to the manslaughter charge. These rules apparently narrowed the scope of admissible facts to those of the physical altercation itself, which meant that Zimmerman’s pursuit of Martin, his 46 police emergency calls, and his hateful words recorded by the 9-1-1 dispatcher on the night he killed Martin were all out of bounds as far as the jury was concerned. These rules saved George Zimmerman from a jail sentence.

Black Zimmerman would not likely have been in a position to benefit from these rules. And herein lies most glaringly the racism of the system of law enforcement and criminal justice, which essentially guaranteed that for Trayvon Martin, like so many black men, justice could not be served.

The Constitution tells us that everyone has a right to a speedy trial, with competent counsel, before a jury of his peers. But in practice, indigent black men almost never receive such a trial and the protections it offers.

In the case of black Zimmerman, a jury of six klansmen would have meant as much as a jury of six NAACP Image Award winners because that jury would never have been empaneled. If you are a black man charged with a crime, you had better be O.J. Simpson because otherwise you probably will not have your day in court. You will not have a chance to get away with it, as George Zimmerman did.

Update: This story was corrected to reflect the fact that the jury in the Zimmerman trial was not entirely white, but included, according to news reports, one Latina woman. We apologize for the error.

The Truth about Trayvon

NY Times, July 16, 2013

By Ekow N. Yankah

The Trayvon Martin verdict is frustrating, fracturing, angering and predictable. More than anything, for many of us, it is exhausting. Exhausting because nothing could bring back our lost child, exhausting because the verdict, which should have felt shocking, arrived with the inevitability that black Americans know too well when criminal law announces that they are worth less than other Americans.

Lawyers on both sides argued repeatedly that this case was never about race, but only whether prosecutors proved beyond a reasonable doubt that George Zimmerman was not simply defending himself when he shot Mr. Martin. And, indeed, race was only whispered in the incomplete invocation that Mr. Zimmerman had “profiled” Mr. Martin. But what this case reveals in its overall shape is precisely what the law is unable to see in its narrow focus on the details.

The anger felt by so many African-Americans speaks to the simplest of truths: that race and law cannot be cleanly separated. We are tired of hearing that race is a conversation for another day. We are tired of pretending that “reasonable doubt” is not, in every sense of the word, colored.

Every step Mr. Martin took toward the end of his too-short life was defined by his race. I do not have to believe that Mr. Zimmerman is a hate-filled racist to recognize that he would probably not even have noticed Mr. Martin if he had been a casually dressed white teenager.

But because Mr. Martin was one of those “punks” who “always get away,” as Mr. Zimmerman characterized him in a call to the police, Mr. Zimmerman felt he was justified in following him. After all, a young black man matched the criminal descriptions, not just in local police reports, but in those most firmly lodged in Mr. Zimmerman’s imagination.

Whether the law judges Trayvon Martin’s behavior to be reasonable is also deeply colored by race. Imagine that a militant black man, with a history of race-based suspicion and a loaded gun, followed an unarmed white teenager around his neighborhood. The young man is scared, and runs through the streets trying to get away. Unable to elude his black stalker and, perhaps, feeling cornered, he finally holds his ground — only to be shot at point-blank range after a confrontation.

Would we throw up our hands, unable to conclude what really happened? Would we struggle to find a reasonable doubt about whether the shooter acted in self-defense? A young, white Trayvon Martin would unquestionably be said to have behaved reasonably, while it is unimaginable that a militant, black George Zimmerman would not be viewed as the legal aggressor, and thus guilty of at least manslaughter.

This is about more than one case. Our reasons for presuming, profiling and acting are always deeply racialized, and the Zimmerman trial, in ignoring that, left those reasons unexplored and unrefuted.

What is reasonable to do, especially in the dark of night, is defined by preconceived social roles that paint young black men as potential criminals and predators. Black men, the narrative dictates, are dangerous, to be watched and put down at the first false move. This pain is one all black men know; putting away the tie you wear to the office means peeling off the assumption that you are owed equal respect. Mr. Martin’s hoodie struck the deepest chord because we know that daring to wear jeans and a hooded sweatshirt too often means that the police or other citizens are judged to be reasonable in fearing you.

We know this, yet every time a case like this offers a chance for the country to tackle the evil of racial discrimination in our criminal law, courts have deliberately silenced our ability to expose it. The Supreme Court has held that even if your race is what makes your actions suspicious to the police, their suspicions are reasonable so long as an officer can later construct a race-neutral narrative.

Likewise, our death penalty cases have long presaged the Zimmerman verdict, exposing how racial disparities, which make a white life more valuable, do not undermine the constitutionality of the death sentence. And even the most casual observer recognizes the painful racial disparities in our prison population — the new Jim Crow, in the account of the legal scholar Michelle Alexander. Our prisons are full of young, black men for whom guilty beyond a reasonable doubt was easy enough to reach.

There is no quick answer for the historical use of our criminal law to reinforce and then punish social stereotypes. But pretending that reasonable doubt is a value-free clinical term, as so many people did so readily in the Zimmerman case, only insulates injustice in plain sight.

Without an honest jurisprudence that is brave enough to tackle the way race infuses our criminal law, Trayvon Martin’s voice will be silenced again.

What would such a jurisprudence look like? The Supreme Court could hold, for example, that the unjustified use of race by the police in determining “reasonable suspicion” constituted an unreasonable stop, tainting captured evidence. Likewise, in the same way we have started to attack racial disparities in other areas of criminal law, we could consider it a violation of someone’s constitutional rights if, controlling for all else, his race was what determined whether the state executed him.

I can imagine a jurisprudence that at least begins to use racial disparities as a tool to question the constitutionality of criminal punishment. And above all, I can imagine a jurisprudence that does not pretend, as lawyers for both sides (but no one else) did in the Zimmerman case, that doubts have no color.

Ekow N. Yankah a professor at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University.

Lady Justice in Sanford, Florida

A New Electricity Divide Threatens to Leave the Less Privileged Behind

Climate Progress (July 15, 2013)

by Jeff Spross

Electricity is undergoing a massive jump forward in technological sophistication — just like telephone communications, the internet, wireless and broadband access have. And while this advancement brings benefits, it also threatens to leave poorer and less privileged Americans behind. That’s the take away of a new paper by Richard Caperton and Mari Hernandez at the Center for American Progress, which also offers a few ideas to get put ahead of the problem.

The first problem is that providing access to new technologies of this sort requires a great deal of costly infrastructure. And from the pure self-interested analysis of actors on the free market, the costs of extending that access to lower-income customers or geographically remote ones exceeds the benefits.

The second problem is that as new technologies become available — in this case, residential solar, energy efficient infrastructure, better battery storage, and other ways to save or self-generate power — it’s the economically privileged that first take advantage of them. That allows them to disconnect from the old technology — in this case, the established electrical grid — first, leaving less privileged customers behind to fund an increasingly expensive infrastructure.

As the paper notes, telephone communication provides an example of what happens next: From 2008 to 2012, wireless-only subscribers jumped 77 percent to encompass 35.8 percent of the American population, while landline-only customers dropped from 17.4 percent to 9.4 percent. Since then, some California customers have seen landline rate hikes of up to 50 percent over the past two years alone. The resulting digital divide, according to a Pew Survey, has left households earning less than $30,000 per year 35 percent less likely to have Internet access than households earning $75,000 or more.

To avoid a similar class divide emerging as solar generation, smart grid technology, and other advancements continue to disrupt the traditional electricity grid, the paper recommends a number of policies:

Repurpose existing electric service programs. The federally funded Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) already provides home energy-bill assistance to low-income households. It could be expanded to include renewable-energy funding. The Rural Utilities Service (RUS) is another federal program that provides financing for electric systems across rural America. It’s in the process of approving a new program providing loans for households to install distributed generation and energy-efficiency tools. It could also be expanded to address any future electrical divide.

Bring regulatory changes to the electric industry. This would treat new energy and grid technology companies the same way as the utilities that previously served the same customers. This would come with practical problems, so an new version of the approach Duke Energy is trying out would mandate that existing utilities offer the technologies that allow customers to disconnect from the grid.

Give companies incentives to address the electrical divide. This could be done through the tax code. For example, a tax credit could encourage distributed generation companies to put solar panels on low-income households. As the paper notes, existing tax incentives for renewable energy have been a tremendous success.

Create a federally owned provider of new energy resources. Decades ago, the U.S. government established the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) to bring electricity to those aforementioned Americans the free market was leaving behind. The government could do the same thing for the emerging market in renewable energy and grid technologies.

As the paper notes, just because the free market, when left to its own devices, would fail to provide universal access does not mean such reticence is best for the economy as a whole. The benefits to economic and job growth of providing universal access are big but often overlooked. Access to these new electricity technologies would bring efficient lighting and cooking options, new opportunities to work, communication tools, educational resources, modern health care services, and increased productivity and competitiveness to tens of millions of poor and underprivileged Americans. It would also help build a broad middle class and customer based for the more advanced products — from appliances to modern computing and communications tools — that are still manufactured in the U.S.

Hunger Games, U.S.A.

New York Times, July 14, 2013

By Paul Krugman

Something terrible has happened to the soul of the Republican Party. We’ve gone beyond bad economic doctrine. We’ve even gone beyond selfishness and special interests. At this point we’re talking about a state of mind that takes positive glee in inflicting further suffering on the already miserable.

The occasion for these observations is, as you may have guessed, the monstrous farm bill the House passed last week.

For decades, farm bills have had two major pieces. One piece offers subsidies to farmers; the other offers nutritional aid to Americans in distress, mainly in the form of food stamps (these days officially known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP).

Long ago, when subsidies helped many poor farmers, you could defend the whole package as a form of support for those in need. Over the years, however, the two pieces diverged. Farm subsidies became a fraud-ridden program that mainly benefits corporations and wealthy individuals. Meanwhile food stamps became a crucial part of the social safety net.

So House Republicans voted to maintain farm subsidies — at a higher level than either the Senate or the White House proposed — while completely eliminating food stamps from the bill.

To fully appreciate what just went down, listen to the rhetoric conservatives often use to justify eliminating safety-net programs. It goes something like this: “You’re personally free to help the poor. But the government has no right to take people’s money” — frequently, at this point, they add the words “at the point of a gun” — “and force them to give it to the poor.”

It is, however, apparently perfectly O.K. to take people’s money at the point of a gun and force them to give it to agribusinesses and the wealthy.

Now, some enemies of food stamps don’t quote libertarian philosophy; they quote the Bible instead. Representative Stephen Fincher of Tennessee, for example, cited the New Testament: “The one who is unwilling to work shall not eat.” Sure enough, it turns out that Mr. Fincher has personally received millions in farm subsidies.

Given this awesome double standard — I don’t think the word “hypocrisy” does it justice — it seems almost anti-climactic to talk about facts and figures. But I guess we must.

So: Food stamp usage has indeed soared in recent years, with the percentage of the population receiving stamps rising from 8.7 in 2007 to 15.2 in the most recent data. There is, however, no mystery here. SNAP is supposed to help families in distress, and lately a lot of families have been in distress.

In fact, SNAP usage tends to track broad measures of unemployment, like U6, which includes the underemployed and workers who have temporarily given up active job search. And U6 more than doubled in the crisis, from about 8 percent before the Great Recession to 17 percent in early 2010. It’s true that broad unemployment has since declined slightly, while food stamp numbers have continued to rise — but there’s normally some lag in the relationship, and it’s probably also true that some families have been forced to take food stamps by sharp cuts in unemployment benefits.

What about the theory, common on the right, that it’s the other way around — that we have so much unemployment thanks to government programs that, in effect, pay people not to work? (Soup kitchens caused the Great Depression!) The basic answer is, you have to be kidding. Do you really believe that Americans are living lives of leisure on $134 a month, the average SNAP benefit?

Still, let’s pretend to take this seriously. If employment is down because government aid is inducing people to stay home, reducing the labor force, then the law of supply and demand should apply: withdrawing all those workers should be causing labor shortages and rising wages, especially among the low-paid workers most likely to receive aid. In reality, of course, wages are stagnant or declining — and that’s especially true for the groups that benefit most from food stamps.

So what’s going on here? Is it just racism? No doubt the old racist canards — like Ronald Reagan’s image of the “strapping young buck” using food stamps to buy a T-bone steak — still have some traction. But these days almost half of food stamp recipients are non-Hispanic whites; in Tennessee, home of the Bible-quoting Mr. Fincher, the number is 63 percent. So it’s not all about race.

What is it about, then? Somehow, one of our nation’s two great parties has become infected by an almost pathological meanspiritedness, a contempt for what CNBC’s Rick Santelli, in the famous rant that launched the Tea Party, called “losers.” If you’re an American, and you’re down on your luck, these people don’t want to help; they want to give you an extra kick. I don’t fully understand it, but it’s a terrible thing to behold.

© 2013 The New York Times