The Atlantic, Aug. 28, 2013

The great leader is not the safe-for-all-political stripes hero he is sometimes portrayed as — and it’s hard to imagine even President Obama fully embracing him.

By Matt Berman

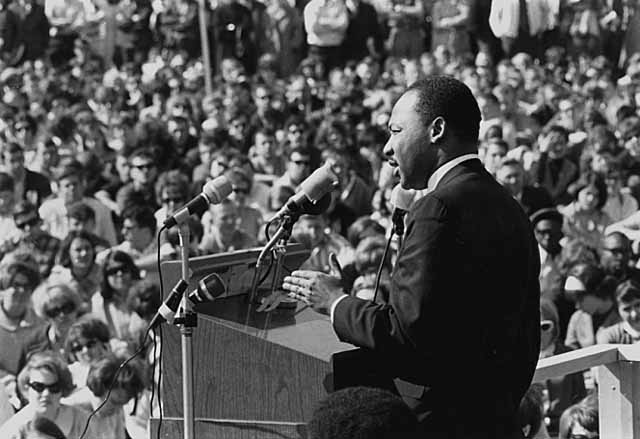

Martin Luther King Jr. was not just the safe-for-all-political-stripes civil-rights activist he is often portrayed as today. He was never just the “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered 50 years ago Wednesday. He was an anti-war, anti-materialist activist whose views on American power would shock many of the same politicians who are currently scrambling to sing his praises.

King’s more radical worldview came out clearly in a speech to an overflow crowd of more than 3,000 people at Riverside Church in New York on April 4, 1967. “The recent statement of your executive committee are the sentiments of my own heart and I found myself in full accord when I read its opening lines: ‘A time comes when silence is betrayal,'” he began. It wasn’t about the civil-rights movement — not directly, at least. “That time has come for us in relation to Vietnam.”

He continued, in a speech called “Beyond Vietnam“:

Tonight, however, I wish not to speak with Hanoi and the NLF [National Liberation Front] but rather to my fellow Americans, who, with me, bear the greatest responsibility in ending a conflict that has exacted a heavy price on both continents…. There is at the outset a very obvious and almost facile connection between the war in Vietnam and the struggle I, and others, have been waging in America. A few years ago there was a shining moment in that struggle. It seemed as if there was a real promise of hope for the poor — both black and white — through the poverty program. There were experiments, hopes, new beginnings. Then came the buildup in Vietnam, and I watched the program broken and eviscerated as if it were some idle political plaything of a society gone mad on war, and I knew that America would never invest the necessary funds or energies in rehabilitation of its poor so long as adventures like Vietnam continued to draw men and skills and money like some demonic destructive suction tube. So I was increasingly compelled to see the war as an enemy of the poor and to attack it as such.

Perhaps the more tragic recognition of reality took place when it became clear to me that the war was doing far more than devastating the hopes of the poor at home. It was sending their sons and their brothers and their husbands to fight and to die in extraordinarily high proportions relative to the rest of the population. We were taking the black young men who had been crippled by our society and sending them 8,000 miles away to guarantee liberties in Southeast Asia which they had not found in southwest Georgia and East Harlem. So we have been repeatedly faced with the cruel irony of watching Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools. So we watch them in brutal solidarity burning the huts of a poor village, but we realize that they would never live on the same block in Detroit. I could not be silent in the face of such cruel manipulation of the poor.

King also addressed the idea that his advocacy of nonviolence at home should extend to the rest of the world:

I knew that I could never again raise my voice against the violence of the oppressed in the ghettos without having first spoken clearly to the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today — my own government.

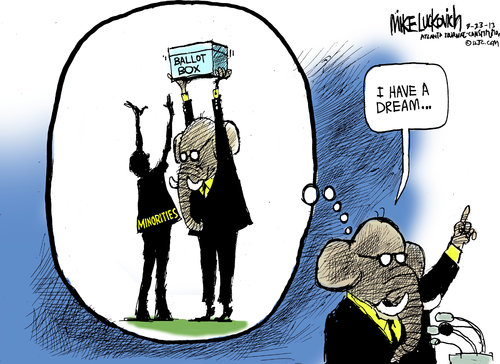

Martin Luther King Jr. is being hailed by politicians of all stripes on Wednesday, from a president who is considering military options in Syria to Republicans like Virginia gubernatorial candidate Ken Cuccinelli. Former Rep. Allen West, R-Fla., wrote an op-ed for U.S. News and World Report on Wednesday, blaming “liberal progressive Democrats” and abortion for blocking King’s vision of equality from becoming a reality. “Dr. King advocated we evaluate the content of one’s character,” West writes. “However, in 2008 Americans voted for someone as president based upon the color of his skin. In 2012, Americans used the same criteria and made the same choice.”

The man who said that his dream of equality was “deeply rooted in the American Dream” also believed the American government, with what he saw as its weapons testing in Vietnam, was on par with “the Germans [who] tested out new medicine and new tortures in the concentration camps of Europe.” In the same speech, King said that, if U.S. actions were to continue, “there will be no doubt in my mind and in the mind of the world that we have no honorable intentions in Vietnam.”

The radicalism of the 1967 speech didn’t just extend to Vietnam. King called for the U.S. to “undergo a radical revolution of values,” saying that “we must rapidly begin the shift from a ‘thing-oriented’ society to a ‘person-oriented’ society.” He continued:

When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.

“A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death,” he said.

The speech, and King’s stance on Vietnam more generally, were not particularly well received by major media outlets at the time. Time magazine called the speech “demagogic slander that sounded like a script for Radio Hanoi.” The Washington Post wrote that King had “diminished his usefulness to his cause, his country, his people.” An April 7, 1963, a New York Times editorial titled “Dr. King’s Error” took a wider view:

By drawing [Vietnam and “Negro equality”] together, Dr. King has done a disservice to both. The moral issues in Vietnam are less clear-cut than he suggests; the political strategy of uniting the peace movement and the civil-rights movement could very well be disastrous for both causes ….

Dr. King can only antagonize opinion in this country instead of winning recruits to the peace movement by recklessly comparing American military methods to those of the Nazis testing “new medicine and new tortures in the concentration camps of Europe.” The facts are harsh, but they do not justify such slander ….

As an individual, Dr. King has the right and even the moral obligation to explore the ethical implications of the war in Vietnam, but as one of the most respected leaders of the civil-rights movement he has an equally weighty obligation to direct that movement’s efforts in the most constructive and relevant way.

King explicitly addressed such questions in his April speech:

Why are you speaking about war, Dr. King? Why are you joining the voices of dissent? Peace and civil rights don’t mix, they say. Aren’t you hurting the cause of your people, they ask? And when I hear them, though I often understand the source of their concern, I am nevertheless greatly saddened, for such questions mean that the inquirers have not really known me, my commitment, or my calling. Indeed, their questions suggest that they do not know the world in which they live.

As he himself said, King was always more than “I Have a Dream.” His other stances — from economic justice to Vietnam — are just more controversial. That doesn’t mean that, 50 years after his historic march, they deserve to be forgotten. The total spectrum of his beliefs may not be as easy as “let freedom ring,” but the full MLK was much larger than the safe-for-everyone caricature that is often presented today.