[Posted by Bill Allen]

WASHINGTON – Sept. 5, 2013 — Today, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) launched an interactive web-based mapping tool that provides the public with access and information on Environmental Impact Statements (EIS) filed with EPA for major projects proposed on federal lands and other proposed federal actions. When visiting the website, users can click on any state for a list of EISs, , including information about the potential environmental, social and economic impacts of these projects.

The National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) requires federal agencies to consider the impacts of proposed actions, as well as any reasonable alternatives as part of their decision-making process. For proposed projects with potentially significant impacts, federal agencies prepare a detailed Environmental Impact Statement which is filed with EPA and made available for public review and comment. EPA is required to review and comment on Environmental Impact Statements prepared by other federal agencies.

“This interactive tool makes it easier for the public to be informed about the environment around them,” said Cynthia Giles, assistant administrator for EPA’s Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance, which oversees NEPA compliance. “Major projects and decisions have the potential to affect the environment where you work and live. I encourage everyone to check out the tool, stay informed and lend your voice.”

The user can click on a state in the map and is provided with comment letters submitted by the EPA on Environmental Impact Statements within the last 60 days. The tool also provides users with the information they need to identify projects with open comment periods, including how to submit comments.

The tool supports EPA’s commitment to utilize advanced information technologies that help increase transparency of its enforcement and compliance programs. EPA’s Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance has recently launched the “Next Generation Compliance” initiative, designed to modernize its approach and drive improved compliance to reduce pollution. Learn more about the effort by visiting: http://blog.epa.gov/epaconnect/2013/08/nextgen/.

To use EPA’s EIS Mapper, visit http://eismapper.epa.gov/.

For more about EPA’s NEPA Program, visit: http://www.epa.gov/compliance/nepa/

More than a million New Jerseans Can’t Afford Nutritious Food

NJSpotlight, Sept. 5, 2013

The U.S. Department of Agriculture says that 12.1 percent of New Jerseyans do not have enough money to ensure a nutritious, active life throughout the year. [The population of New Jersey is 8.8 million people, so 12.1% is over a million people without food security.–P.M.]

What’s more, 4.6 percent are considered to have very low food security, which is defined as at least one member of a household being forced to reduce food intake and disrupt eating patterns. [That’s 400,000 people in New Jersey without enough to eat.]

According to the USDA, the problem of food insecurity is typically shielded from children, although nationally 1.2 percent of children face the problem along with their families. [There are 74 million children in the U.S., so 1.2% is almost 900,000 children without enough to eat.]

New Jersey Policy Perspective, a left-leaning think tank, released a statement along with the USDA data arguing that this is the wrong time to cut Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program funds, also known as food stamps, as Congress is expected to consider doing next week.

Naomi Klein: Why unions need to join the climate fight

[Posted by Molly Greenberg]

Climate Connections, Sept. 3, 2013

Source URL: http://goo.gl/9RVXQH

By Naomi Klein

I’m so very happy and honoured to be able to share this historic day with you.

The energy in this room – and the hope the founding of this new union has inspired across the country – is contagious.

It feels like this could be the beginning of the fight back we have all been waiting for, the one that will chase Harper from power and restore the power of working people in Canada.

So welcome to the world UNIFOR.

A lot of your media coverage so far has focused on how big UNIFOR is – the biggest private sector union in Canada. And when you are facing as many attacks as workers are in this country, being big can be very helpful. But big is not a victory in itself.

The victory comes when this giant platform you have just created becomes a place to think big, to dream big, to make big demands and take big actions. The kind of actions that will shift the public imagination and change our sense of what is possible.

And it’s that kind of “big” that I want to talk to you about today.

Some of you are familiar with a book I wrote called The Shock Doctrine. It argues that over the past 35 years, corporate interests have systematically exploited various forms of mass crises – economic shocks, natural disasters, wars – in order to ram through policies that enrich a small elite, by shredding regulations, cutting social spending and forcing large-scale privatizations.

As Jim Stanford and Fred Wilson argue in their paper laying out UNIFOR’s vision, the attacks working people in Canada and around the world are facing right now are a classic case of The Shock Doctrine.

There’s no shortage of examples, from the mass slashing of salaries and layoffs of public sector workers in Greece, to the attacks on pension funds in Detroit in the midst of a cooked up bankruptcy, to the Harper government’s scapegoating of unions for its own policy failures right here in Canada.

I don’t want to spend my time with you proving that this ugly tactic of exploiting public fear for private gain is alive and well. You know it is; you are living it.

I want to talk about how we fight it.

And I’ll be honest with you: when I wrote the book, I thought that just understanding how the tactic worked, and mobilizing to resist it, would be enough to stop it. We even had a slogan: “Information is shock resistance. Arm yourself.”

But I have to admit something to you: I was wrong. Just knowing what is happening – just rejecting their story, saying to the politicians and bankers: “No, you created this crisis, not us” or “No, we’re not broke, it’s just that you are hording all the money” may be true but it’s not enough.

It’s not even enough when you can mobilize millions of people in the streets to shout “We won’t pay for your crisis.” Because let’s face it – we’ve seen massive mobilizations against austerity in Greece, Spain, Italy, France, Britain. We’ve occupied Wall Street and Bay Street and countless other streets. And yet the attacks keep coming.

Some of the new movements that have emerged in recent years have staying power, but too many of them arrive, raise huge hopes, and then seem to disappear or fizzle out.

The reason is simple. We are trying to organize in the rubble of a 30 year war that has been waged on the collective sphere and workers rights. The young people in the streets are the children of that war.

And the war has been so complete, so successful, that too often these social movements don’t have anywhere to stand. They have to occupy a park or a square to have a meeting. Or they are able to build a power base in their schools, but that base is transient by its nature, they are out in a few years.

This transience makes these movements far too easy to evict simply by waiting them out, or by applying brute state force, which is what has happened in far too many cases.

And this is one of the many reasons why the creation of UNIFOR, and your promise of reviving Social Unionism – building not just a big union but a vast and muscular network of social movements – has raised so much hope.

Because our movements need each other.

The new social movements bring a lot to the table – the ability to mobilize huge numbers of people, real diversity, a willingness to take big risks, as well as new methods of organizing including a commitment to deep democracy.

But these movements also need you – they need your institutional strength, your radical history, and perhaps most of all, your ability to act as an anchor so that we don’t keep rising up and floating away.

We need you to be our fixed address, our base, so that next time we are impossible to evict.

And we also need your organizing skills. We need to figure out together how to build sturdy new collective structures in the rubble of neoliberalism. Your innovative idea of community chapters is a terrific start.

It’s also important to remember that you are not starting from scratch. A remarkable group of people gathered a little less than a year ago for the Port Elgin Assembly and produced what they called the Making Waves agenda.

The most important message to come out of that process is that our coalitions cannot just be about top-down agreements between leaders; the change has to come from the bottom up, with full engagement from members.

And that means investing in education. Education about the ideological and structural reasons why we have ended up where we are. If we are going to build a new world, our foundation must be solid.

It also means getting out there and talking to people face to face. Not just the public, not just the media, but re-invigorating your own members with the analysis we share.

But there’s something else too. Another reason why we can’t seem to win big victories against the Shock Doctrine.

Even when there is mass resistance to an austerity agenda, and even when we understand how we got here, something is stopping us – collectively – from fully rejecting the neoliberal agenda.

And I think what it is is that we don’t fully believe that it’s possible to build something in its place. For my generation, and younger, deregulation, privatization and cutbacks is all we’ve ever known.

We have little experience building or dreaming. Only defending. And this is what I’ve come to understand as the key to fighting the Shock Doctrine.

We can’t just reject the dominant story about how the world works. We need our own story about what it could be.

We can’t just reject their lies. We need truths so powerful that their lies dissolve on contact with them. We can’t just reject their project. We need our own project.

Now, we know Stephen Harper’s project – he has only one idea for how to build our economy.

HARPER’S ONE IDEA

Dig lots of holes, lay lots of pipe. Stick the stuff from the pipes onto ships – or trucks, or railway cars – and take it to places where it will be refined and burned. Repeat, but more and faster. Before anyone figures out that this is his one idea, and what has allowed him to maintain the illusion that he is some kind of responsible economic manager, while the rest of the economy falls apart.

It’s why it’s so important to this government to accelerate oil and gas production at an outrageous pace, and why it has declared war on everyone standing in the way, whether environmentalists or First Nations or other communities.

It’s also why the Harper government is willing to sacrifice the manufacturing base of this country, waging war on workers, attacking your most basic collective rights.

This is not just about extracting specific resources – Harper represents an extreme version of a particular worldview. One that I sometimes call “extractivism”. And others times simply call capitalism.

EXTRACTIVISM

It’s an approach to the world based on taking and taking without giving back. Taking as if there are no limits to what can be taken – no limits to what workers’ bodies can take, no limits to what a functioning society can take, no limits to what the planet can take.

In the extractivist mindset, labour is a commodity just like the bitumen. And maximum value must be extracted from that resource – ie you and your members – regardless of the collateral damage. To health, families, social fabric, human rights.

When crisis hits, there is only ever one solution: take some more, faster. On all fronts.

So that is their story – the one we’re trapped in. The one they use as a weapon against all of us.

And if we are going to defeat it, we need our own story.

CLIMATE CHANGE – DON’T LOOK AWAY

So I want to offer you what I believe to be the most powerful counter-narrative to that brutal logic that we have ever had.

Here it is: our current economic model is not only waging war on workers, on communities, on public services and social safety nets. It’s waging war on the life support systems of the planet itself. The conditions for life on earth.

Climate change. It’s not an “issue” for you to add to the list of things to worry about it. It is a civilizational wake up call. A powerful message – spoken in the language of fires, floods, storms and droughts – telling us that we need an entirely new economic model, one based on justice and sustainability.

It’s telling us that when you take you must also give, that there are limits past which we cannot push, that our future health lies not in digging ever deeper holes but in digging deeper inside ourselves – to understand how ALL our fates are interconnected.

Oh, and one last thing. We need to make this transition, like, yesterday. Because our emissions are going in exactly the wrong direction and there’s very little time left.

Now I know talking about climate change can be a little uncomfortable for those of you working in the extractive industries, or in manufacturing sectors producing carbon-intensive products like cars and planes.

I also know that despite your personal fears, you haven’t joined the deniers like some of your counterparts in the U.S. – both of your former unions have all kinds of great climate policies on the books.

And this isn’t some recent conversion either: the CEP courageously fought for Kyoto all the way back in the 90s. The CAW has been fighting against the environmental destruction of free trade deals even longer. [Former CEP President] Dave Coles even got arrested protesting the Keystone XL pipeline. That was heroic.

But…how to say this politely?…I think it’s fair to say that climate change hasn’t traditionally been your members greatest passion.

And I can relate: I’m not an environmentalist. I’ve spent my adult life fighting for economic justice, inside our country and between countries. I opposed the WTO not because of its effects on dolphins but because of its effects on people, and on our democracy.

The case I want to make to you is that climate change – when its full economic and moral implications are understood – is the most powerful weapon progressives have ever had in the fight for equality and social justice.

But first, we have to stop running away from the climate crisis, stop leaving it to the environmentalist, and look at it. Let ourselves absorb the fact that the industrial revolution that led to our society’s prosperity is now destabilizing the natural systems on which all of life depends.

I’m not going to bore you with a whole bunch of numbers. Though I could remind you that the World Bank says we’re on track for a four degrees warmer world. That the International Energy Agency – not exactly a protest camp of green radicals – says the Bank is being too optimistic and we’re actually in for 6 degrees of warming this century, with “catastrophic implications for all of us”. That’s an understatement: we haven’t even reached a full degree of warming yet and look at what is already happening.

CLIMATE CHANGE – IS HAPPENING NOW

97% of the Greenland ice-sheet’s surface was melting last summer – as Bill McKibben says, we’ve taken one of the great features of the planet and broken it.

And then there are the extreme weather events. Hell, I was in Fort McMurray this summer and the contents of the town’s museum – literally, its history – was floating around in the water.

I was trying to get interviews with the big oil companies but their headquarters in Calgary were all empty as the downtown was dark and the city was frantically bailing out from the worst flood it has ever seen.

And not even the provincial NDP had the courage to say: this is what climate change looks like and we are going to have a lot more of it if those oil companies get their way.

We know that this climate emergency is only getting more dire. And our excuses about why we can’t do anything about it – why it’s somebody else’s issue – are melting away.

But engaging on climate does not mean dropping everything else you are doing and turning into a raving environmentalist.

Because I know that the fights you are already waging against austerity, against new free trade deals, against attacks on unions have never been more important.

Which is why I’m not calling you to drop anything.

CLIMATE CHANGE – IS AT THE HEART OF ALL OUR EXISTING DEMANDS

My argument is that the climate threat makes the need to fight austerity all the more pressing, since we need public services and public infrastructure to both bring down our emissions and prepare for the coming storms.

Far from trumping other issues, climate change vindicates much of what the left has been demanding for decades.

In fact, climate change turbo-charges our existing demands and gives them a basis in hard science. It calls on us to be bold, to get ambitious, to win this time because we really cannot afford any more losses. It enflames our vision of a better world with existential urgency.

What I’m going to show you is that confronting the climate crisis requires that we break every rule in the free-market playbook – and that we do so with great urgency.

CLIMATE ACTION = THE LEFT AGENDA

So I’m going to quickly lay out what I believe a genuine climate action plan would look like. And it’s not the market-driven non-sense we hear from some of the big green groups in the U.S. – changing your light bulbs, or carbon trading and offsetting. This is the real deal, getting at the heart of why our emissions are soaring.

And you will notice that a lot this will sound familiar. That’s because much of this agenda is already embraced in the vision of your new union, not to mention everything you have been fighting for in the past.

First of all, we need to revive and reinvent the public sphere. If we want to lower our emissions, we need subways, streetcars and clean-rail systems that are not only everywhere but affordable to everyone.

We need energy-efficient affordable housing along those transit lines. We need smart electrical grids carrying renewable energy. We need garbage collection that has, as its goal, the elimination of garbage.

And we don’t just need new infrastructure. We need major investments in the old infrastructure to cope with the coming storms. For decades we have fought against the steady starving of the public sphere.

Again and again we’ve seen how those decades of cuts have left us more vulnerable to climate disasters: superstorms bursting through decaying levees, heavy rain washing sewage into lakes, wildfires raging as fire crews are underpaid and understaffed. Bridges and tunnels buckling under the new reality of heavy weather.

Far from taking us away from the fight for a robust public sphere, climate change puts us right in the middle of it – but this time armed with arguments that raise the stakes significantly. It is not hyperbole to say that our future depends on our ability to do what we have so long been told we can no longer do: act collectively. And who better than unions to carry that message?

The renewal of the public sphere will create millions of new, high paying union jobs – jobs in fields that don’t hasten the warming of the planet.

But it’s not just boilermakers, pipefitters, construction workers and assembly line workers who get new jobs and purpose in this great transition.

There are big parts of our economy that are already low-carbon.

They’re the parts facing the most disrespect, demeaning attacks and cuts. They happen to be jobs dominated by women, new Canadians, and people of colour.

And they’re also the sectors we need to expand massively: the care-givers, educators, sanitation workers, and other service sector workers. The very ones that your new union has pledged to organize. The low-carbon workers who are already here, demanding living wages and respect. Turning low-paying low-carbon jobs into higher-paying jobs is itself a climate solution and should be recognized as such.

Here I think we should take inspiration from the fast-food workers in the United States and their historic strikes this past week. They are showing how this organizing can be done. Maybe it will turn out to be the first uprising in a sustained rebellion fighting for both real wages and real food! One in which the health of the workers and the health of society are inextricably linked.

It should be clear by now that I am not suggesting some half-assed token “green jobs” program. This is a green labour revolution I’m talking about. An epic vision of healing our country from the ravages of the last 30 years of neoliberalism and healing the planet in the process.

Environmentalists can’t lead that kind of revolution on their own. No political party is rising to the challenge. We need you to lead.

HOW TO PAY FOR IT

So the big question is: how are we going to pay for all this?

I mean, we’re broke, right? Or so our government is always telling us.

But with stakes this high, crying broke isn’t going to cut it. We know that it’s always possible to find money to bail out banks and start new wars. So that means we have to go to where the money is, and the money is with the fossil fuel companies and the banks that finance them. We have to get our hands on some of their super profits to help clean up the mess they made. It’s a simple concept, well established in law: the polluter pays.

We know we can’t get the money by continuing to extract more. So as we wind down our dependence on fossil fuels, as we extract LESS, we have to keep MORE of the profits.

There’s lots of ways to do that. A national carbon tax and higher royalties are the most obvious. A financial transaction tax would be a big help. Raising corporate taxes across the board would too.

When you do that, suddenly, digging holes and laying pipe isn’t the only option on the table.

Quick example. A recent study from the CCPA compared the public value from a five billion dollar pipeline – Enbridge Gateway for instance – and the value from the same amount of money invested in green economic development.

Spend that money on a pipeline, you get mostly short-term construction jobs, big private sector profits, and heavy public costs for future environmental damage.

Spend that money on public transit, building retrofits and renewable energy, and you get, at the very least, three times as many jobs…not to mention a safer future. The actual number of jobs could be many times more than that, according to their modeling. At the highest end, green investment could create 34 times more jobs than just building another pipeline.

And how do you raise five billion dollars for public investments like that? A minimal national carbon tax of ten dollars a tonne would do the trick. And there would be five billion new dollars every year. Unlike the one-off Enbridge put on the table.

Environmentalists, and I include myself here, have to do a much better job of not just saying no to projects like Northern Gateway but also forcefully saying yes to our solutions about how to build and finance green infrastructure.

Now: these alternatives makes perfect sense on paper, but in the real world, they slam headlong into the dominant ideology that tells us that we can’t increase taxes on corporations, that we can’t say no to new investment, and moreover, that we can’t actively decide what kind of economy we want – that we are supposed to leaving it all to the magic of the market.

Well – we’ve seen how the private sector manages this crisis. It’s time to get back in there. This transition needs to be publicly managed. And that will mean everything from new crown corporations in energy, to a huge re-distribution of power, infrastructure and investment.

A democratically-controlled, de-centralized energy system operated in the public interest. This agenda is increasingly being described as “energy democracy” and it’s not a new idea in the union world – Sean Sweeney of the Global Labor Institute at Cornell University is here today, and many fine trade unions – including CEP – have been working on this agenda for years. It’s time to turn energy democracy into a reality here in Canada. “Power to the people” is a terrific slogan to start with.

As you all know, there have been some modest attempts by provincial governments to play a more activist role in bringing about a green transition, while resisting the pressure to double down on dirty energy.

But in those cases, we’re starting to see something very disturbing. In the provinces where governments have taken the most positive, bold action, they’re getting dragged into trade court.

And that brings me to the last piece of a real progressive climate agenda.

TRADE

It’s time to rip up so-called Free Trade deals once and for all. And we sure as hell can’t be signing new ones.

You’ve fought them for decades now, since the CAW played such a pivotal role in the battle against the first Free Trade deal with the US. You’ve fought them because they undermine workers rights both here and abroad, because they drive a race to the bottom, because they hyper-empower corporations.

And you were right – even more right than you knew. Because not only is corporate globalization largely responsible for soaring emissions, but now the logic of free trade is directly blocking us from making the specific changes needed to reduce climate chaos in response.

A couple of quick examples.

Ontario’s Green Energy plan is far from perfect. But it has a very sensible “buy local” provision so that wind and solar projects in Ontario actually deliver jobs and economic benefits to local communities. It’s the core principle of a just transition.

Well, the World Trade Organization has decided that this measure is illegal.

The CAW is already in a coalition fighting back – but more green policies will face the same corporate challenges.

Here’s another example. Quebec banned fracking – a courageous move that has been taken up by two consecutive governments.

But a US drilling company is planning to sue Canada for $250- million dollars under NAFTA’s Chapter 11, claiming the ban interferes with its “valuable right to mine for oil and gas under the St. Lawrence river.”

We should have seen this coming. A WTO official was quoted almost a decade ago, saying that the WTO enables challenges against “almost any measure to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

In other words, these maniacs think trade should trump everything, including the planet itself. If there has ever been an argument to stop this madness, climate change is it.

The battle lines have never been clearer. Climate change is the argument that must trump all others in the battle against corporate free trade. I mean, sorry guys, but the health of our communities and our planet is just a little more important than your god-given right to obscene profits.

These are moral arguments we can win.

And we don’t have to wait for governments to give us permission. Next time they close a factory making fossil-fuel machinery – whether cars, tractors, or airplanes – don’t let them do it.

Do what workers are doing from Argentina to Greece to Chicago: occupy the factory. Turn it into a green worker co-op. Go beyond negotiating a last, sad severance. Demand the resources – from companies and governments – to start building the new economy right now.

Whether that’s electric trains or windmills. Watch that factory turn into a beacon for students, anti-poverty activists, environmentalists, First Nations. All fighting together for that vision.

Climate change is a tool. Pick it up and use it. Use it to demand the supposedly impossible.

It’s not a threat to your jobs, it’s the key to liberation from a logic that is already waging a war on the entire concept of dignified work.

So all we need is the political power to make this vision a reality. And that power can be built on the urgency and science of the climate crisis.

If we stay true to a clear vision that these changes are what is required to stave off an ecological collapse, then we will change the conversation.

We’ll escape from the clutches of narrow free-market economics, where we are constantly told to ask for less and expect less and we will find ourselves in a conversation about morality – about what kind of people we want to be, about what kind of world we want for ourselves and our kids.

If we set the terms of that conversation, we back Stephen Harper up against the wall.

We finally hold him accountable for the lethal ideology he serves – the one that he has been hiding behind that bland and boring mask of his.

That’s how you shift the balance of forces in this country.

If UNIFOR becomes the voice for a boldly different economic model, one that provides solutions to the attacks on working people, on poor people, and the attacks on the Earth itself, then you can stop worrying about your continued relevance.

You will be on the front lines of the fight for the future, and everyone else – including the opposition parties – will have to follow or be left behind.

FIRST NATIONS

I believe that a key to this shift is deepening your alliance with First Nations, whose constitutionally guaranteed title to land and resources is the biggest legal barrier Harper faces to his vision of Canada as an extraction and export machine – a country-sized sacrifice zone.

As my friend Clayton Thomas Mueller says, imagine if the workers and First Nations actually joined forces in a meaningful coalition – the rightful owners of the land, side by side with the people working the mines and pipelines, coming together to demand another economic model?

People and the earth itself on one side, predatory capitalism on the other.

The Harper Tories wouldn’t know what hit them.

But this is about more than strategic alliances. As we tell our own story of a different Canada to stand up to Harper’s story about endless extraction, we will need to learn from the Indigenous worldview. The one that understands that you can’t just take and take, but also care-take, and give back whenever you harvest. That five-year-plans are for kids, and grownups think about seven generations. A worldview that reminds us that there are always unforeseen consequences because everything is connected.

Because building the kinds of deep coalitions that we need begins with identifying the threads that connect all of our struggles. And indeed that recognize they are the SAME struggle.

I want to leave you with a word that might help. Overburden.

OVERBURDEN

When I was in the tar sands earlier this summer, I kept thinking about it. Overburden is the word used by mining companies to describe the “waste earth covering a mineral deposit.”

But mining companies have a strange definition of waste. It includes forests, fertile soil, rocks, clay – basically anything that stands between them and the gold, copper, or bitumen they are after.

Overburden is the life that gets in the way of money. Life treated as garbage.

As we passed pile after pile of masticated earth by the side of the road, it occurred to me that it wasn’t just the dense and beautiful Boreal forest that was “overburden” to these companies.

We are all overburden. That’s certainly the way the Harper government sees us.

– Unions are overburden since the rights you have won are a barrier to unfettered greed.

– Environmentalists are overburden, because they are always going on about climate change and oil spills.

– Indigenous people are overburden, since their rights and court challenges get in the way.

– Scientists are overburden, since their research proves what I’ve been telling you.

– Democracy itself is overburden to our government – whether it’s the right of citizens to participate in an environmental assessment hearing, or the right of Parliament to meet and debate the future of the country.

This is the world deregulated capitalism has created, one in which anyone and anything can find themselves discarded, chewed up, tossed on the slag heap.

But “overburden” has another meaning. It also means, simply, “to load with too great a burden”; to push something or someone beyond their limits.

And that’s a very good description of what we’re experiencing too.

Our crumbling infrastructure is overburdened by new demands and old neglect.

Our workers are overburdened by employers who treat their bodies like machines.

Our streets and shelters are overburdened by those whose labour has been deemed disposable.

The atmosphere is overburdened with the gasses we are spewing into it.

And it is in this context that we are hearing shouts of “enough!” from all quarters. This much and NO further.

We heard it from the fast food worker in Milwaukee, who went on strike this week holding a sign saying, “I am worth more” and helped set off a national debate about inequality.

We heard it from the Quebec Students last summer, who said “No” to a tuition increase and ended up unseating a government and sparking a national debate about the right to free education.

We heard it from the four women who said “No” to Harper’s attacks on environmental protections and indigenous rights, pledging to be Idle No More, and ended up setting off an indigenous rights uprising across North America.

And we are hearing “Enough” from the planet itself as it fights back in the only ways it can.

Everywhere, life is reasserting itself. Insisting that it is not overburden.

We are starting to realize that not only have we had enough – but that there is enough.

To quote Evo Morales, there is enough for all of us to live well. There just isn’t enough for some of us to live better and better.

To close off, I want to read an excerpt from Article 2 of your brand new constitution.

Words that many of us have been waiting a very long time to hear. Words that you may have already heard today, but they bear repeating. Here goes…

“Our goal is transformative. To reassert common interest over private interest.

Our goal is to change our workplaces and our world. Our vision is compelling.

It is to fundamentally change the economy, with equality and social justice, restore and strengthen our democracy and achieve an environmentally sustainable future.

This is the basis of social unionism – a strong and progressive union culture and a commitment to work in common cause with other progressives in Canada and around the world.”

Brothers and Sisters, all I would add is: don’t say it if you don’t mean it.

Because we really, really need you to mean it.

Thank you.

Labor Day: Considering the Legacy of Stolen Labor

Racism Review, Sept. 2, 2013

By Jessie

On this Labor Day, I’m thinking about the legacy of stolen labor. While Labor Movement-created-holiday is meant to commemorate the “social and economic achievements of American workers,” a post from a friend, Son of Baldwin, has me thinking about labor that was not freely given, but rather was taken from people and for which they were not compensated.

(Facebook post from Son of Baldwin)

What does that legacy of stolen labor look like today? If it were a bar graph, it might look something like this:

(Graph from Demos – Stats from 2010 Survey of Consumer Finances)

As you can see, black and Latino families have much less wealth than white families, even when you compare within the same income groups. Matt Bruenig, writing at Demos, asks, “why is this the case?” and then answers his own question with the following:

“There are many factors, but one in particular looms large. It turns out that three centuries of enslavement followed by another bonus century of explicit racial apartheid was hell on black wealth accumulation. Wealth accumulation opportunities haven’t exactly been evenly distributed in the last half century either. Because wealth is the sort of thing you transmit across generations and down family lines (e.g. through inheritance, gifts, and so on), racial wealth disparities remain quite massive.”

And, indeed, if we look at the wealth accrued to those who enslaved others, just in the U.S., the estimates from economists put those numbers in the trillions, in 2011 dollars.

(Source: Measuring Worth.com)

In their understated, scholarly language, the creators of the chart – Williamson and Cain – write:

“Slavery in the United States was an institution that had a large impact on the economic, political and social fabric on the country. This paper gives an idea of its economic magnitude in today’s values. As noted in the introduction, they can be conservatively described as large.”

So, the impact of slavery in the US was large? Got it. But slavery ended in 1865. Everything’s been fine since then, hasn’t it?

Not really.

Profiting from Stolen Labor Now

Deadria Farmer-Paellmann is researcher who is documenting the way contemporary corporations benefit from slavery. Many of the companies we use today initially established those profitable entities by profiting from stolen labor. For example, many of the current insurance companies began by insuring slaves, as with an 1854 Aetna policy insuring three slaves owned by Thomas Murphy of New Orleans. Farmer-Paellmann has located evidence of connections to slavery from a number of other corporations, including:

- FleetBoston (purchased by BankofAmerica) traced to slave-trading merchant

- Brown Brothers gave loans to planters to buy enslaved people

- Original Lehman Brother owned seven enslaved people

- Majority of labor for Southern rail companies done by enslaved people

In 2000, Aetna expressed “regret for any involvement” it “may have” had in insuring slaves. Today, the company stands by that statement and says it has been able to locate “only” seven policies insuring 18 slaves. “We stood up; we apologized; we tried to do the right thing,” said Aetna spokesman Fred Laberge.

That was all a long, long time ago. Aetna apologized. Besides, what’s all this got to do with now, today? These companies built their wealth, either partially or in whole, on labor that was stolen from people who didn’t have a choice and who were never compensated for that labor.

These corporations with legacy-connections to slavery are not the only ones profiting from stolen labor now. For-profit corporations are making millions off of locking people up. CCA, which I’ve written about here before, and The Geo Group are among the worst offenders here.

(Source)

Federal Prison Industries, also known as UNICOR, is a US-owned government corporation created in 1934 that uses penal labor from the Federal Bureau of Prisons to produce goods and services (UNICOR has no access to the commercial market but sells products and services to federal government agencies). The statistics about UNICOR’s use of prison labor, perhaps the quintessence of contemporary stolen labor, are staggering.

These U.S. federal prison labor statistics are from Prison Policy (pulled from UNICOR Annual Reports):

These wages at federal prison are criminal, and the ones at state facilities are even worse. Nevada, for example, pays inmates just .13 cents/hour for their labor.

There’s no possibility of organizing these workers, however, since the U.S. Supreme Court has upheld a North Carolina warden’s ban on prisoners’ right to form a labor union.

Addressing the Legacy of Stolen Labor & the Contemporary Racial Wealth Gap

To address this legacy of stolen labor, some have called for reparations.

US Rep. John Conyers has introduced H.B.40, Commission to Study Reparation Proposals for African Americans Act, into every session of Congress since 1989, and vows to keep doing so until it is passed into law.

In 2002, a group of U.S. legal scholars led by Charles Ogletree (Harvard) started litigating the legacy of slavery to get redress from some of the corporations that benefited. A number of people, mostly political conservatives, oppose reparations.

More recently, representatives from more than a dozen Caribbean nations are uniting in an effort to get reparations for slavery from three former colonial powers: Britain, France and the Netherlands. Leaders from The Caribbean Community (Caricom) are launching a united effort to seek compensation for the lingering legacy of the Atlantic slave trade.

A much more modest proposal, as Bruenig of Demos suggests, is a steep, progressive inheritance tax in the U.S. If the proceeds of such a tax were directed to a full-fledged sovereign wealth fund that pays out social dividends, we could address a number of social ills at once.

It’s actually not hard to think of ways to address the legacy of stolen labor and stolen wealth. It simply involves the transfer of capital. And, there is precedent for it in the U.S.

The federal government reached a consent decree with a class of over 20,000 black farmers to compensate for years of discrimination by the Department of Agriculture. Previously, the government also approved significant compensation for Japanese-Americans interned during World War II and paid reparations to black survivors of the Rosewood, FL [pdf], massacre.

What we lack to address the legacy of stolen labor and the contemporary reality of a racial wealth gap is the collective political will to do the right thing.

Walking While Black in the ‘White Gaze’

N.Y. Times, Sept. 1, 2013

By George Yancy

“Man, I almost blew you away!”

Those were the terrifying words of a white police officer — one of those who policed black bodies in low income areas in North Philadelphia in the late 1970s — who caught sight of me carrying the new telescope my mother had just purchased for me.

“I thought you had a weapon,” he said.

The words made me tremble and pause; I felt the sort of bodily stress and deep existential anguish that no teenager should have to endure.

Did Trayvon Martin’s death happen in Dr. King’s ‘dream’ or Malcolm X’s ‘American nightmare’?

This officer had already inherited those poisonous assumptions and bodily perceptual practices that make up what I call the “white gaze.” He had already come to “see” the black male body as different, deviant, ersatz. He failed to conceive, or perhaps could not conceive, that a black teenage boy living in the Richard Allen Project Homes for very low income families would own a telescope and enjoyed looking at the moons of Jupiter and the rings of Saturn.

A black boy carrying a telescope wasn’t conceivable — unless he had stolen it — given the white racist horizons within which my black body was policed as dangerous. To the officer, I was something (not someone) patently foolish, perhaps monstrous or even fictional. My telescope, for him, was a weapon.

In retrospect, I can see the headlines: “Black Boy Shot and Killed While Searching the Cosmos.”

That was more than 30 years ago. Only last week, our actual headlines were full of reflections on the 1963 March on Washington, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, and President Obama’s own speech at the steps of the Lincoln Memorial to commemorate it 50 years on. As the many accounts from that long ago day will tell you, much has changed for the better. But some things — those perhaps more deeply embedded in the American psyche — haven’t. In fact, we should recall a speech given by Malcolm X in 1964 in which he said, “For the 20 million of us in America who are of African descent, it is not an American dream; it’s an American nightmare.”

II.

Despite the ringing tones of Obama’s Lincoln Memorial speech, I find myself still often thinking of a more informal and somber talk he gave. And despite the inspirational and ethical force of Dr. King and his work, I’m still thinking about someone who might be considered old news already: Trayvon Martin.

In his now much-quoted White House briefing several weeks ago, not long after the verdict in the trial of George Zimmerman, the president expressed his awareness of the ever-present danger of death for those who inhabit black bodies. “You know, when Trayvon Martin was first shot, I said that this could have been my son,” he said. “Another way of saying that is Trayvon Martin could have been me 35 years ago.” I wait for the day when a white president will say, “There is no way that I could have experienced what Trayvon Martin did (and other black people do) because I’m white and through white privilege I am immune to systemic racial profiling.”

Obama also talked about how black men in this country know what it is like to be followed while shopping and how black men have had the experience of “walking across the street and hearing the locks click on the doors of cars.” I have had this experience on many occasions as whites catch sight of me walking past their cars: Click, click, click, click. Those clicks can be deafening. There are times when I want to become their boogeyman. I want to pull open the car door and shout: “Surprise! You’ve just been car-jacked by a fantasy of your own creation. Now get out of the car.”

The president’s words, perhaps consigned to a long-ago news cycle now, remain powerful: they validate experiences that blacks have undergone in their everyday lives. Obama’s voice resonates with those philosophical voices (Frantz Fanon, for example) that have long attempted to describe the lived interiority of racial experiences. He has also deployed the power of narrative autobiography, which is a significant conceptual tool used insightfully by critical race theorists to discern the clarity and existential and social gravity of what it means to experience white racism. As a black president, he has given voice to the epistemic violence that blacks often face as they are stereotyped and profiled within the context of quotidian social spaces.

III.

David Hume claimed that to be black was to be “like a parrot who speaks a few words plainly.” And Immanuel Kant maintained that to be “black from head to foot” was “clear proof” that what any black person says is stupid. In his “Notes on Virginia,” Thomas Jefferson wrote: “In imagination they [Negroes] are dull, tasteless and anomalous,” and inferior. In the first American Edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1798), the term “Negro” was defined as someone who is cruel, impudent, revengeful, treacherous, nasty, idle, dishonest, a liar and given to stealing.

My point here is to say that the white gaze is global and historically mobile. And its origins, while from Europe, are deeply seated in the making of America.

Black bodies in America continue to be reduced to their surfaces and to stereotypes that are constricting and false, that often force those black bodies to move through social spaces in ways that put white people at ease. We fear that our black bodies incite an accusation. We move in ways that help us to survive the procrustean gazes of white people. We dread that those who see us might feel the irrational fear to stand their ground rather than “finding common ground,” a reference that was made by Bernice King as she spoke about the legacy of her father at the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

The white gaze is also hegemonic, historically grounded in material relations of white power: it was deemed disrespectful for a black person to violate the white gaze by looking directly into the eyes of someone white. The white gaze is also ethically solipsistic: within it only whites have the capacity of making valid moral judgments.

Even with the unprecedented White House briefing, our national discourse regarding Trayvon Martin and questions of race have failed to produce a critical and historically conscious discourse that sheds light on what it means to be black in an anti-black America. If historical precedent says anything, this failure will only continue. Trayvon Martin, like so many black boys and men, was under surveillance (etymologically, “to keep watch”). Little did he know that on Feb. 26, 2012, that he would enter a space of social control and bodily policing, a kind of Benthamian panoptic nightmare that would truncate his being as suspicious; a space where he was, paradoxically, both invisible and yet hypervisible.

“I am invisible, understand, simply because people [in this case white people] refuse to see me.” Trayvon was invisible to Zimmerman, he was not seen as the black child that he was, trying to make it back home with Skittles and an iced tea. He was not seen as having done nothing wrong, as one who dreams and hopes.

As black, Trayvon was already known and rendered invisible. His childhood and humanity were already criminalized as part of a white racist narrative about black male bodies. Trayvon needed no introduction: “Look, the black; the criminal!”

IV.

Many have argued that the site of violence occurred upon the confrontation between Trayvon and Zimmerman. Yet, the violence began with Zimmerman’s non-emergency dispatch call, a call that was racially assaultive in its discourse, one that used the tropes of anti-black racism. Note, Zimmerman said, “There’s a real suspicious guy.” He also said, “This guy looks like he’s up to no good or he’s on drugs or something.” When asked by the dispatcher, he said, within seconds, that, “He looks black.” Asked what he is wearing, Zimmerman says, “A dark hoodie, like a gray hoodie.” Later, Zimmerman said that “now he’s coming toward me. He’s got his hands in his waist band.” And then, “And he’s a black male.” But what does it mean to be “a real suspicious guy”? What does it mean to look like one is “up to no good”? Zimmerman does not give any details, nothing to buttress the validity of his narration. Keep in mind that Zimmerman is in his vehicle as he provides his narration to the dispatcher. As “the looker,” it is not Zimmerman who is in danger; rather, it is Trayvon Martin, “the looked at,” who is the target of suspicion and possible violence.

After all, it is Trayvon Martin who is wearing the hoodie, a piece of “racialized” attire that apparently signifies black criminality. Zimmerman later said: “Something’s wrong with him. Yep, he’s coming to check me out,” and, “He’s got something in his hands.” Zimmerman also said, “I don’t know what his deal is.” A black young male with “something” in his hands, wearing a hoodie, looking suspicious, and perhaps on drugs, and there being “something wrong with him,” is a racist narrative of fear and frenzy. The history of white supremacy underwrites this interpretation. Within this context of discursive violence, Zimmerman was guilty of an act of aggression against Trayvon Martin, even before the trigger was pulled. Before his physical death, Trayvon Martin was rendered “socially dead” under the weight of Zimmerman’s racist stereotypes. Zimmerman’s aggression was enacted through his gaze, through the act of profiling, through his discourse and through his warped reconstruction of an innocent black boy that instigates white fear.

V.

What does it say about America when to be black is the ontological crime, a crime of simply being?

Perhaps the religious studies scholar Bill Hart is correct: “To be a black man is to be marked for death.” Or as the political philosopher Joy James argues, “Blackness as evil [is] destined for eradication.” Perhaps this is why when writing about the death of his young black son, the social theorist W.E.B. Du Bois said, “All that day and all that night there sat an awful gladness in my heart — nay, blame me not if I see the world thus darkly through the Veil — and my soul whispers ever to me saying, ‘Not dead, not dead, but escaped; not bond, but free.’ ”

Trayvon Martin was killed walking while black. As the protector of all things “gated,” of all things standing on the precipice of being endangered by black male bodies, Zimmerman created the conditions upon which he had no grounds to stand on. Indeed, through his racist stereotypes and his pursuit of Trayvon, he created the conditions that belied the applicability of the stand your ground law and created a situation where Trayvon was killed. This is the narrative that ought to have been told by the attorneys for the family of Trayvon Martin. It is part of the narrative that Obama brilliantly told, one of black bodies being racially policed and having suffered a unique history of racist vitriol in this country.

Yet it is one that is perhaps too late, one already rendered mute and inconsequential by the verdict of “not guilty.”

========

George Yancy is a professor of philosophy at Duquesne University. He has authored, edited and co-edited 17 books, including “Black Bodies, White Gazes,” “Look, a White!” and (co-edited with Janine Jones) “Pursuing Trayvon Martin.”

A Rumble in the Sky, and Grumbles Below

[Posted by Bill Allen]

N.Y. Times, Aug. 25, 2013

La Guardia Airport’s new Tennis Climb concentrates planes over a swath of Queens, irritating residents below. Previous routes, the Whitestone Climb and the Flushing Climb, which was created to divert planes from the United States Open, were more dispersed.

By Cara Buckley

It is known as the Flushing Climb — an airplane route born 23 years ago to prevent planes taking off at La Guardia Airport from disturbing fans at Arthur Ashe Stadium during the United States Open.

But the Federal Aviation Administration, as part of an effort to deal with congested airspace, has quietly approved for much more frequent use a version of the route in which planes, rather than fanning out, fly a narrower, more precise path. This has infuriated residents of Queens living underneath, who contend they had no say in the change and that the noise has become unbearable.

The F.A.A., however, concluded that the noise impact of the narrower route, christened the Tennis Climb, was permissible, even though the agency conducted a six-month test run last year — without telling the public — that yielded a flood of complaints. Part of the problem in determining who is right is that there are not enough noise monitors in New York, unlike other cities, to accurately track the cumulative impact of the noise, some elected officials said.

For many officials, activists and New Yorkers, the F.A.A.’s move was yet another example of what they see as the agency’s overriding community anguish in pursuit of its own ends. They fear that airplane noise will worsen as more planes fill the skies, and that the public will have little recourse.

The Tennis Climb from La Guardia is now used throughout the year to allow greater use of certain runways at Kennedy Airport. Unlike earlier departure routes that fanned outward and headed east, then north, its path looks as slim as a feather. The route was tailored for planes equipped with new GPS-based precision navigation.

But hewing to a narrower line often means that the same houses are flown over again and again.

“It’s like having screaming jet engines right over your house,” said Janet McEneaney, who has lived in Bayside, Queens, for 15 years, and last year founded a group called Queens Quiet Skies. “You can’t even have a conversation in your own living room. You can’t hear the television. You can’t talk on the phone.” The planes might start at 6 a.m., she said, and stop at 2 a.m.

More airlines are expected to embrace precision navigation to reduce fuel consumption and emissions. The F.A.A. and the airlines say it will actually reduce the problem of noise because fewer people will be affected. And when planes use precision navigation to descend, they say, the aircrafts can almost glide in rather than keeping their engines powered up, resulting in lower emissions and less noise.

“Geographically, the aircraft will always be over the same spot every day — the same house,” said Joe Devito, manager of flight standards compliance at JetBlue, whose entire fleet is equipped with the technology. But “under the old procedures, I’d come in with engines powered up,” he said. “Today I’m going over the house with the engines on idle. That’s nice and quiet.”

But some wonder whether the airlines and the F.A.A. have underestimated, or understated, the noise impact, especially in the case of the Tennis Climb.

Under terms of the 2012 Congressional act funding the F.A.A., precision navigation can be exempt from extensive environmental studies if it is deemed to have no significant environmental impact, or to reduce fuel consumption, emissions and noise per flight. But gauging the noise has proved difficult.

A recent report found that the F.A.A. did not have the technology to track the noise of each flight. There are also disagreements over what constitutes “significant” impact. While the F.A.A. concluded that noise generated by the Tennis Climb was not significant, Queens residents heartily disagree.

“People are saying it’s 10 times louder than it was ever,” said State Senator Tony Avella, a Democrat of Queens. He and other elected officials are pushing the agency to conduct a more thorough environmental review.

The adoption of precision navigation coincides with another F.A.A. effort: redesigning the nation’s airspace to improve efficiency and reduce delays. The F.A.A. said the projects were not related. But in its analysis of the airspace redesign, the Government Accountability Office noted that the agency failed to account for how loud precision navigation might be for some residents, saying the technology “may have resulted in fewer people impacted by noise but to a greater degree.”

Indeed, New Yorkers who have long battled airplane noise fear that precision navigation will worsen the problem. And some in communities including Park Slope and Bedford-Stuyvesant, both in Brooklyn, say they have already been subjected to far noisier skies in recent years, with planes seemingly flying lower, and with increased frequency.

However, officials say that they have not introduced any new precision navigation routes over those neighborhoods — though planes equipped with that technology can use pre-existing routes — and that flight altitudes have not changed.

“The only thing that has changed are the wind and weather patterns, which determine the runways we use, so we are using arrival routes over Brooklyn slightly more often than in previous years,” Laura Brown, an F.A.A spokeswoman, said.

Kendall Lampkin, the executive director of a Nassau County coalition that has pushed for quieter airspace around Kennedy Airport for more than 40 years, said that while noise had seemed to worsen over communities there, it remained a “back-burner” issue for the F.A.A. and the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which operates the region’s biggest airports.

While the F.A.A. uses computer modeling to gauge noise impact, as allowed by law, activists and elected officials say readings from noise monitors are needed. Yet La Guardia and Kennedy have just 15 noise monitors between them, compared with 33 at O’Hare Airport in Chicago and 30 in metropolitan Boston. The Port Authority is upgrading its noise monitoring system and is considering adding monitors, a spokesman said.

There are limits on airplane noise; the federal government uses a measure called a day-night average sound level, which averages airplane noise exposure over a year. A spokesman for the Port Authority said that thanks to quieter plane engines, few pockets of the city matched or exceeded the allowable limit of 65 decibels, and those that did were quickly shrinking. Together with the F.A.A., the authority has soundproofed 77 schools, with its share of the cost being $360 million.

A bill recently passed in the New York Legislature would require the Port Authority to conduct a sweeping study of the cumulative noise levels and land use compatibility around the city’s airports. That study, which dozens of other airports have undertaken, could result in planes’ being rerouted and also open the door to federal financing for soundproofing homes. The bill awaits Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo’s signature. For the study to go ahead, a similar bill would have to pass the New Jersey Legislature and be signed by Gov. Chris Christie.

For years, the Port Authority has resisted executing the study, saying its noise monitoring and soundproofing efforts were sufficient. Plus, said Chris Valens, an authority spokesman, “there is simply not enough funding in the Port Authority or F.A.A. budgets to soundproof private homes and businesses.”

Compared with standards set in Europe and by other federal agencies, the F.A.A.’s measure for gauging how loud is too loud is unusually lenient. Other federal bodies and councils, including the Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Environmental Protection Agency and the National Research Council, recommend a day-night measure of 55 decibels.

Henry Young, an aviation consultant, said the limit of 65 decibels was created when the prime concern about noise was hearing loss. But now, there is a wider realization of other ill effects, like high blood pressure and stress.

Mr. Young, who strongly backs the noise study, said the maximum allowable level should be 55 decibels. “In the end, people sleep, students get better grades, houses are worth more money,” he said. “Nothing but good stuff is going to come out of this program.”

Link: http://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/26/nyregion/planes-roar-from-above-creates-a-rumble-on-the-ground.html?nl=nyregion&emc=edit_ur_20130826&_r=1&

We Should Add Climate Change to the Civil Rights Agenda

BET, August 22, 2013

Environmental issues should be a part of the next wave of the movement.

By Phaedra Ellis Lamkins

This week, tens of thousands of people from across America are streaming into the nation’s capital to observe the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington — and Green for All will be among them.

We’re marching against the recent attack on voting rights. We’re demanding justice in the face of Stand Your Ground laws and racial profiling. We’re marching to raise awareness on unemployment, poverty, gun violence, immigration and gay rights. And we are calling for action on climate change.

Chances are, when you think about civil rights, environmental issues aren’t on the radar screen. But stop and think about it. Remember Hurricane Katrina?

The hurricane that leveled New Orleans showed that severe weather in low-income neighborhoods and communities of color is a matter of life and death. The images from the storm are hard to forget: bodies floating in water for days and thousands of people stranded without shelter, waiting for help that was too slow to come.

It’s not difficult to see how injustice and inequality played out during Hurricane Katrina. Thousands of people were subjected to needless loss, suffering, even death — just because they didn’t have the resources to prepare and escape the storm.

What’s harder to see is the imminent threat that severe weather — occurring with increased frequency and voracity — poses to our communities. We should never again witness the kind of devastation and preventable suffering we saw during Katrina. That’s why we have to add climate change to our retooled list of what the civil rights movement stands for.

Climate change isn’t just an environmental issue; it’s about keeping our communities safe. It’s a matter of justice. Because when it comes to disasters — from extreme temperatures to storms like Katrina — people of color are consistently hit first and worst.

African-Americans living in L.A. are more than twice as likely to die in a heat wave as other residents in the city, thanks to an abundance of pavement and lack of shade, cars and air conditioning in neighborhoods with the fewest resources. Factor in a steady rise in temperature — last year was the hottest year on record in the U.S. — and we’re looking at an urgent problem.

Meanwhile, our communities are at the tip of the spear when it comes to pollution. Fumes from coal plants don’t just accelerate climate change — they cause asthma, heart disease and cancer, leading to 13,000 premature deaths a year. And people of color are once again most vulnerable; 68 percent of African-Americans live within 30 miles of a toxic coal plant. That might help explain why one out of six Black kids suffers from asthma, compared with one in ten nationwide.

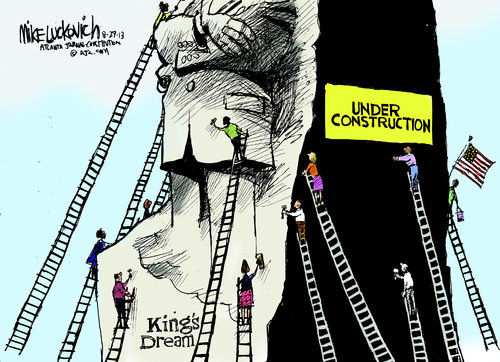

But that’s not the only reason we should pay attention. Fighting global warming — the right way — will get us closer to achieving the dream Martin Luther King Jr. spoke about on that day in Washington 50 years ago.

The solutions to climate change won’t just make us safer and healthier — they are one of the best chances we’ve had in a long time to cultivate economic justice in our communities. Clean energy, green infrastructure and sustainable industries are already creating jobs and opportunity. There’s a clean tech boom unfolding right now that is on par with the tech boom that made Silicon Valley. And this time, we don’t want to miss the boat.

If we do this right, we can make sure the steps we take to fight pollution also build pathways into the middle class for folks who have been locked out and left behind. These green jobs are real — 3.1 million Americans already have them. And because they pay more (13 percent above the median wage) while requiring less formal education, they are exactly what’s needed to eradicate poverty in our communities.

We have work to do to make sure more people of color have access to the opportunities created by responding to climate change. But if we are successful, we will help create a world where our kids can breathe clean air and drink clean water; where we’re safe and resilient in the face of storms; where more of us share in the nation’s prosperity.

This is Dr. King’s dream reborn. And fighting climate change helps get us there.

So, even as we confront the pressing dangers and injustices that cry for an immediate response — like attacks on our right to vote or racial profiling — we can’t lose sight of the future. We need to respond to climate change today to ensure safe, healthy, prosperous lives for our kids tomorrow.

Phaedra Ellis-Lamkins is CEO of Green for All, a national organization working to build an inclusive green economy.

Obama speech: “A More Perfect Union”

Politico Mojo, Aug. 28, 2013

By Lauren Williams

On March 18, 2008 in Philadelphia, then-Senator Barack Obama delivered a speech that is considered by many to be one of the greatest speeches on race in America’s history. Our own David Corn wrote that the speech, which Obama gave in response to the controversy surrounding his former pastor, Rev. Jeremiah Wright, was “unlike any delivered by a major political figure in modern American history.”

When Obama talks about race, he makes waves (see his surprise press conference after the Zimmerman verdict for a more recent example). Wednesday, when he delivers a speech on the National Mall to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, he’s expected to speak about race again. As a reminder of how good he can be when he does, watch 2008’s “A More Perfect Union:”

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=zrp-v2tHaDo]

What Happened to Jobs and Justice?

N.Y. Times, Aug. 28, 2013

By William P. Jones

Madison, Wis. — On Aug. 28, 1963, nearly a quarter of a million people thronged the nation’s capital for the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the largest civil rights demonstration in American history. Its impact on American politics was tremendous: in addition to building support to pass the civil rights bill that President John F. Kennedy had recently proposed, marchers succeeded in strengthening and expanding the scope of the bill far beyond what the president had envisioned.

For many, the most important addition was Title VII, which prohibited employers and unions from discriminating on the basis of race, color, religion, national origin and sex. The ban on sex discrimination was itself a further amendment, introduced in January 1964 by Southern Democrats who hoped it would impede the bill’s progress through Congress. Their plan backfired: not only did they fail to scuttle the bill, but their amendment also provided a critical legal tool in the fight for women’s equality.

The message of the march still resonated in 1965, when Congress passed the Voting Rights Act, Medicare and Medicaid, key features of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s proposal to bring “an end to poverty and racial injustice.”

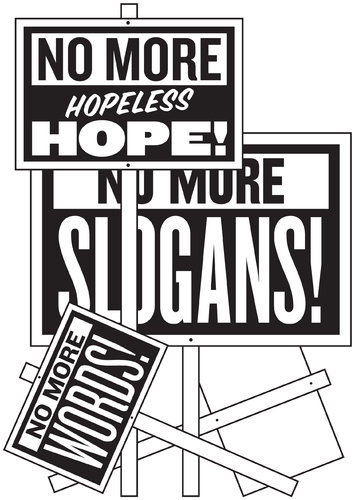

The march was so successful that we often forget that it occurred in a political environment not so different from our own. Kennedy’s victory over Richard M. Nixon in 1960 signaled a break from the conservatism of the 1950s. But like the election of Barack Obama in 2008, hope for a return to the liberalism of the 1930s was dampened by an administration that rejected “old slogans” like wage increases and public works in favor of tax cuts and free trade to stimulate growth.

That disillusionment gave rise to sit-ins and freedom rides against segregation in the South, but those protests proved powerless in the face of entrenched conservative power. In contrast, the grass-roots movements that gained political influence in the Kennedy years were White Citizens Councils, the John Birch Society and other forces that, much like today’s Tea Party movement, shifted the political spectrum to the right.

Given those obstacles, how did the March on Washington help drive support for such sweeping civil rights and domestic policy measures?

First, it linked the protest movements of the 1960s to institutions with longstanding roots in working-class communities. The initial call for the 1963 demonstration came from the Negro American Labor Council, an organization of black trade unionists that used local networks to plan for the march months before it was officially announced.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee played similar roles in the South, mobilizing local civil rights groups, black churches and students. Support also came from the National Council of Negro Women and other elements of the black women’s movement that had battled poverty and discrimination since the 19th century.

At the same time, organizers rallied supporters around a broad and ambitious set of demands. A. Philip Randolph, the veteran trade unionist who had first called for a march on Washington to protest employment discrimination in 1941, wanted the demonstration to focus on the shortcomings of Kennedy’s economic policies. Pointing out that black workers were restricted to entry-level jobs that were most vulnerable to the automation and offshoring of manufacturing under way in the 1960s, he warned that without measures to end discrimination and create more jobs, blacks would be condemned to struggling for survival “within the grey shadows of a hopeless hope.”

Other black leaders shared that concern, but some worried that a “march for jobs” would compete with the movement that the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and others were leading against legalized discrimination and disfranchisement. Anna Arnold Hedgeman, a prominent leader of the black women’s movement, persuaded the men to plan a demonstration that would address “both the economic problems and civil rights.”

Finally, while Randolph, King, Hedgeman and others expanded the mobilization to include a broad and multiracial coalition, they resisted pressure to moderate their tactics or demands.

Both black and white liberals worried that an angry protest would turn moderates in Congress against Kennedy’s civil rights bill, but Randolph and King convinced the leaders of the N.A.A.C.P., the United Auto Workers and the National Urban League that the demonstration would be peaceful and effective.

It was the combination of these stalwart positions and rich institutional networks with the sheer number of peaceful black and white marchers that persuaded so many Americans of the rightness of civil rights and antipoverty legislation.

As we celebrate the 50th anniversary of the march, however, its central achievements are more imperiled than ever. This summer the Supreme Court upheld the principles behind the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act while severely weakening authority to enforce them. We have a charismatic liberal president and inspiring protest movements dedicated to racial equality and economic justice — but, as in the Kennedy years, they have proved no match for well-organized conservatives.

The solution may not be another march on Washington. But real changes in policy, and the defense of previous victories, require the combination of institutional backing, coalition building and ambitious demands that brought so many people to the National Mall in 1963.

========

William P. Jones is a professor of history at the University of Wisconsin and the author of “The March on Washington: Jobs, Freedom and the Forgotten History of Civil Rights.”