CounterPunch, Jan. 29, 2014

By Tanya Golash-Boza

In a recent interview, David Leonard argued that white people do not suffer from the structural violence that white supremacy creates. He contends: “As it relates to the criminal justice system, health, economic security, wealth, or education, white people are not hurt by racism.”

I have tremendous respect for David Leonard as a scholar and critic, and have learned a great deal from his writings. Moreover, I greatly appreciate most of what he has to say in this insightful interview, conducted by activist and writer, Suey Park. And, the arguments that racism primarily affects people of color and that whites benefit from structural racism are hard to disagree with.

However, I take issue with the claim that racism does no harm to white people. Racism is a scourge on our society, and white people are part of our society. Moreover, eradicating racism will require a multi-racial coalition. If white people are not hurt by racism, why would they fight against it? It is from this standpoint that I felt compelled to write this piece on racism and white America. Once we see the harm that racism causes all people in our society, it will be easier to form multi-racial coalitions to eliminate racism.

What is Racism and How Does It Affect Us?

Racism refers to both (1) the belief that races exist and some are better than others, and (2) the practice of subordinating races believed to be inferior. For example, an employer can think African Americans are less competent than whites – this belief constitutes racial prejudice. When that employer decides to hire a white person instead of an equally qualified black person, that decision may be considered racial discrimination.

Both racial prejudice and discrimination are widespread.

In one study, sociologist Joe Feagin found that three-quarters of whites agreed with prejudicial statements about blacks, such as “blacks have less native intelligence” than whites. In 1995, researchers conducted a study in which they asked participants to close their eyes for a second and imagine a drug user. Fully 95 percent of respondents reported imagining a black drug user. The reality is that African Americans account for only 15 percent of drug users in the United States and are just as likely as whites to use drugs. However, Americans have an unconscious bias toward blacks and imagine them to be more likely to use drugs. These and other studies show the widespread nature of racial prejudice. They also show that many white Americans believe racist lies: blacks are not inherently less intelligent than whites nor are they more likely to use drugs. One way racism affects white people negatively is that racism distorts whites’ worldviews. When you buy into racism, you are buying into and propagating a set of harmful lies.

Researchers have also consistently found that racial discrimination is pervasive. One study of Department of Defense employees revealed that nearly half of the black respondents had heard racist jokes in the previous year. Another survey revealed that 80% of black respondents had encountered racial hostility in public places. An African American secretary interviewed by sociologists Joe Feagin and Karyn McKinney details the consequences of constant discrimination: “I had to see several doctors because of the discrimination, and I went through a lot of stress. And, then, my blood pressure … went on the rise.” This woman, like many other African Americans they interviewed, displayed high levels of stress due to mistreatment in the workplace and consequently had health issues. A recent study from the University of Maryland even shows that black men are likely to die earlier than whites because racism speeds up cellular aging.

It is undeniable that racial prejudice and discrimination are widespread and that these beliefs and practices negatively affect non-whites. But, do they negatively affect white people?

Racism Holds Us Back

In some cases, it is clear that racially discriminatory practices benefit white people. When an African-American is passed over for a job for their perceived incompetence, a white person can directly benefit from that racial discrimination by getting hired. When teachers presume that Latino students are not interested in attending college, white students in that classroom may benefit from extra mentoring and encouragement. So, yes, I agree that racism is beneficial to whites insofar as it gives whites unearned benefits and privileges – especially in those situations where we are talking about finite resources – one job or a teacher’s attention.

However, racism has also created a situation where highly qualified people of color are passed over for important opportunities. In this schema, mediocre white people are teaching our children, leading community businesses, and fixing our telephones. Sure, this benefits the mediocre white people who get the jobs, but, when we prevent talented people of color from succeeding, we are holding back our society as a whole. When half of black children in the United States grow up in poverty, we have to wonder how many brilliant minds are unable to reach their full potential.

In 1869, philosopher John Stuart Mill argued that “the legal subordination of one sex to the other — is wrong itself, and now one of the chief hindrances to human improvement.” In 1949, French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir wrote that the “slavery of half of humanity” was preventing humanity from reaching its full potential. One could apply Mills and de Beauvoir’s reflections on sexism to racism: by subordinating nearly half of the children in the United States, we are holding back the whole country. Racism is especially detrimental to people of color, but has negative repercussions for everyone insofar as it is a hindrance to human development.

The Structural Advantages of Whiteness

Individual discriminatory actions can be distinguished from structural racism – policies, laws, and institutions that reproduce racial inequalities. On the whole, it seems quite obvious that whites benefit from structural racism: it creates racial inequality, which puts whites at the top in terms of wealth. In 2009, African Americans and Latinos had less than 8 percent of the wealth of whites. The figures for Native Americans are similar: in 2000, the average Native American born between 1957 and 1965 had only $5,700 in wealth, compared with his or her white counterpart, who had amassed $65,500 in wealth. And, in 2009, Asian families had about half the wealth of white families. In 2009, one-third of black and Latino households had zero or negative wealth. To the extent that wealth is a zero-sum game (which is not entirely true), whites benefit directly from the structural racism that leads to wealth inequality.

Through racist policies and practices, white people are able to concentrate wealth into their own hands. In this way, racism benefits those white people with access to this wealth.

However, most people in the United States do not have access to wealth: 1% of Americans own nearly half of the wealth in this country. And, the top 20 percent of the population controls over 80 percent of the wealth. Globally, the figures are even more alarming: the 85 wealthiest people in the world control the same amount as wealth as half of the global population.

The rest of us are fighting over the crumbs.

The People United?

One might expect high levels of inequality in the United States to lead to massive unrest. Yet they have not, in large part due to racism. This works in two ways. 1) Racism divides workers from one another, preventing multi-racial coalitions that might lead to workers working together for better wages and benefits. 2) The United States government has created a complex system of social control designed to prevent unrest. This system is the punitive arm of the state: mass incarceration.

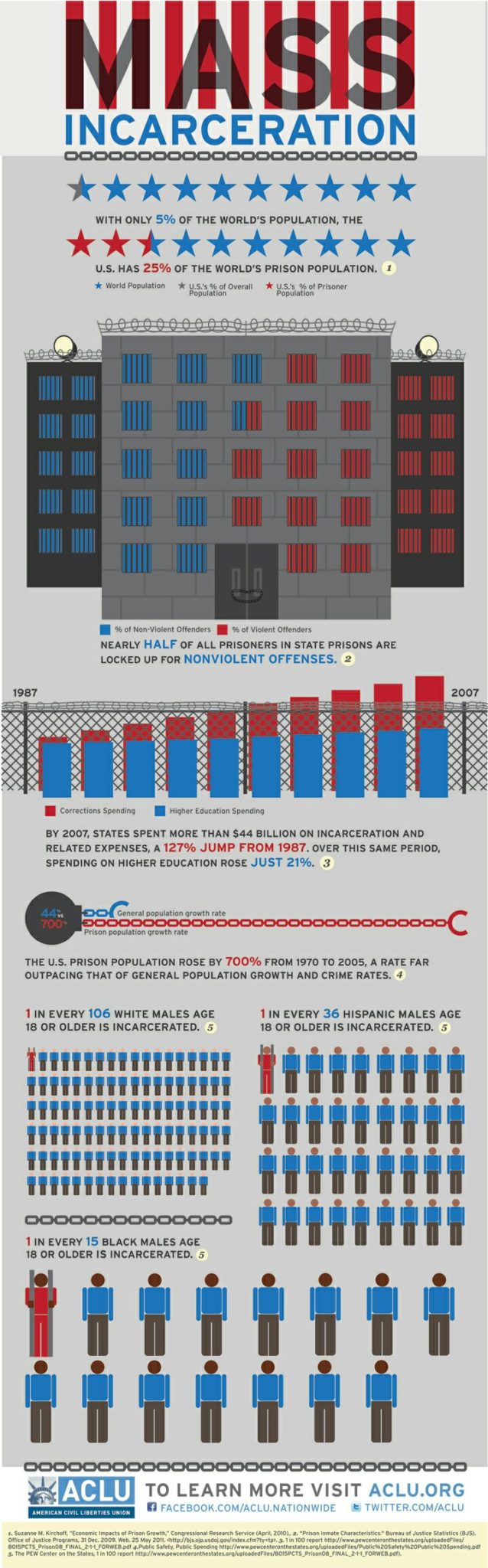

Mass incarceration is a system rife with structural racism – from laws designed to punish blacks more severely to racial profiling to discriminate sentencing and discriminatory judges. This structural racism creates a situation where whites are less likely to be incarcerated than blacks and Latinos. However, the country as a whole does not benefit from the fact that misguided racist ideologies provide the justification for the United States government to waste billions of dollars every year putting people behind bars.

The negative effects of incarceration are not limited to people behind bars – incarceration also affects their families and communities as well as every taxpayer whose taxes pay for mass incarceration. Michelle Alexander, for example, recently argued that we have spent a trillion dollars waging the War on Drugs, and could use that money to improve our schools and libraries. Neill Franklin made a similar argument here. Instead of spending billions of dollars each year putting black men in prison, we could be using that money to better our communities.

The United States has more people in prison than any other country and incarcerates people at a higher rate than at any other time in history. Our crime rate, however, is neither higher than in other countries nor greater than it has been historically. Why, then, are so many Americans behind bars? One major reason that we have large numbers of people in prison is that many people in this country operate under the misguided belief that mass incarceration reduces crime. Furthermore, this misbelief is grounded in racialized fears, particularly of black and Latino men – who are disproportionately affected by mass incarceration.

Between 1970 and 2000, incarceration rates in the United States increased five-fold, due in large part to legislation designed to fight drugs. (The War on Drugs has a much longer racist history, by the way.) Drug offenders represent “the most substantial source of growth in incarceration in recent decades, rising from 40,000 persons in prison and jail in 1980 to 450,000 today.” The irony is that the incarceration of drug offenders is a highly ineffective way to reduce the amount of illegal drugs sold in the United States. When street-level drug sellers are incarcerated, they are quickly replaced by other sellers, since what drives the drug market is demand for drugs. Incarcerating large numbers of drug offenders has not ameliorated the drug problem in the United States. (For an example of drug policy that actually works, we can look to Portugal, which saw a massive reduction in drug use once it was decriminalized.)

Zealous enforcement of drug laws disproportionately affects people of color, even though whites are actually more likely to use and sell drugs. In the United States, black men are sent to prison on drug charges at thirteen times the rate of white men, yet five times as many whites as blacks use illegal drugs.

Do white people benefit from black people being sent to jail? The answer to this question would only be “yes” if you think that there are a finite number of jail beds. This, however, is not the case. Instead, the federal and state governments went on a building frenzy in the 1980s and 1990s to create jail beds to lock up drug offenders. This rush to build jails was based on the misguided and racist belief that drug offenders are dangerous.

One of these drug offenders was African-American Cornell Hood II. In February 2011, he was convicted of attempting to distribute marijuana and sentenced to life in prison. Does the average white person benefit from the lifetime incarceration of Cornell Hood? Or, are we all worse off because of this unnecessary government expenditure? The recent legalization of marijuana in Colorado makes Hood’s life sentence all the more outrageous.

Mass incarceration has been condoned by American voters in large part because of entrenched racism. And, of course, white people are not fully protected from the War on Drugs. Even though white people are less likely to be arrested, charged, and sentenced to prison, when they are sentenced, they face the same mandatory minimum sentences that everyone else does. And, therefore, white people can also end up serving life sentences for marijuana distribution.

Racism is an ideology that makes us believe that some people are less worthy than others. This, in turn, causes us to condone our local, state, and federal governments spending money to protect us from these other, less desirable people. This is a massive waste of resources and is harmful to everyone – including white people.

Part of fighting against racism involves understanding that racism affects each group differently. Racist drug policies mostly harm African Americans; and racist immigration policies mostly harm Latinos. However, these racist policies ultimately affect everyone in society because the laws are – at least on paper – color-blind.

It is in the best interest of white people to join forces with people of color and fight for a society free of racism – a society that would be ultimately better for everyone. When white people fight against racism, we are fighting to end a system that provides structural advantages to whites, yet does so at the expense of our society and our humanity.

Tanya Golash-Boza is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Merced. She is the author of: Race and Racisms: A Critical Approach, Yo Soy Negro Blackness in Peru, Immigration Nation: Raids, Detentions and Deportations in Post-9/11 America, and Due Process Denied: Detentions and Deportations in the United States. She blogs at:http://stopdeportationsnow.blogspot.com

Tweets: (twitter handle: @tanyaboza )