This article was originally published by Planet Detroit on September 28, 2023.

By: Brian Allnut

Experts say all Michigan residents could benefit from the transparency in the Garden State’s pollution rules for overburdened communities.

Theresa Landrum has been fighting for environmental justice in Detroit’s heavily polluted 48217 zip code for decades, where residents suffer from disproportionate rates of asthma, cancer, respiratory problems, heart disease, miscarriages, and birth defects, all of which are associated with air pollution.

Yet companies like Marathon Petroleum and Edward C. Levy continue to pursue permits that could bring even more pollution.

Landrum said this year’s wildfire smoke worsened the bad air, turning the sky orange and leaving her coughing for days. Indeed, new research shows that although the nation’s air quality had improved following the passage of the Clean Air Act in 1970, in many states wildfire smoke has slowed or reversed much of this progress over the last two decades.

But, she said, the new smoke threat could bring more urgency to efforts to control air pollution from other sources. “We’re not looking at cumulative impacts from all these industries,” she said.

Activists like Landrum are focused on the collective impact of pollution from multiple sources, often concentrated in low-income areas and communities of color such as southwest Detroit. Facilities are regulated on a case-by-case basis, although a permit could be denied if it will increase the level of one of six pollutants covered by the National Ambient Air Quality Standards and the area is already out of compliance for that pollutant.

This approach can allow for a heavy overall pollution burden, even though individual businesses are operating within legal emissions limits.

The concept of regulating cumulative impacts is slowly gaining traction. In January, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency released guidance outlining its authority to consider cumulative impacts in its decisions. And at least 12 state legislatures have considered or adopted legislation addressing cumulative risk or impacts, according to a University of Michigan analysis released last year.

To address this issue in Michigan, Landrum is working with a statewide coalition of environmental groups to push for cumulative impact legislation, influenced by New Jersey’s landmark 2020 environmental justice law that restricted the issuing of new permits or expansion of facilities in overburdened communities.

Michigan could learn from the approach organizers took in New Jersey, advocates say. There, activists worked for years on legislation that was finally passed when the Black Lives Matter movement and public health concerns related to COVID helped galvanize support.

Yet, advocates say passing a law in Michigan may require a slightly different approach, with a need to build support in both urban and rural areas to challenge a powerful industrial lobby in a state where Democrats hold a slim majority in the legislature.

“The health impacts, the air quality impacts, the water quality impacts are something that both rural people and urban folks that are on the fence line of big industry are dealing with,” said Christy McGillivray, legislative and political director for the Sierra Club Michigan Chapter.

She said a smart strategy in Michigan could look at the impacts of industrial agriculture and other industries in farm country as well as urban pollution to build a broad constituency for a cumulative impact bill.

New Jersey sets a precedent

Melissa Miles, executive director of the New Jersey Environmental Justice Alliance, said New Jersey’s 2020 law came at the end of a years-long effort to bring more protections for overburdened communities in the state.

“EJ groups never dropped that banner of cumulative impacts, even when it was unpopular, even when there wasn’t political will,” Miles said.

She said the key to getting the New Jersey law over the finish line were the specific circumstances of 2020 that brought justice concerns to the fore.

“This moment happened nationally that was heard around the world, which was the Black Lives Matter movement,” Miles said. “When Black people say, ‘we can’t breathe,’ it could be the result of the quick, violent deaths at the hands of law enforcement, or it could be the slow, silent death due to air pollution.”

The disproportionate impacts from COVID-19 in Black and brown communities also highlighted the relationship between particulate matter pollution and poor health outcomes during the pandemic.

Miles said New Jersey environmental justice advocates were ready to help inform policy-making when these tragic circumstances created an appetite for reform.

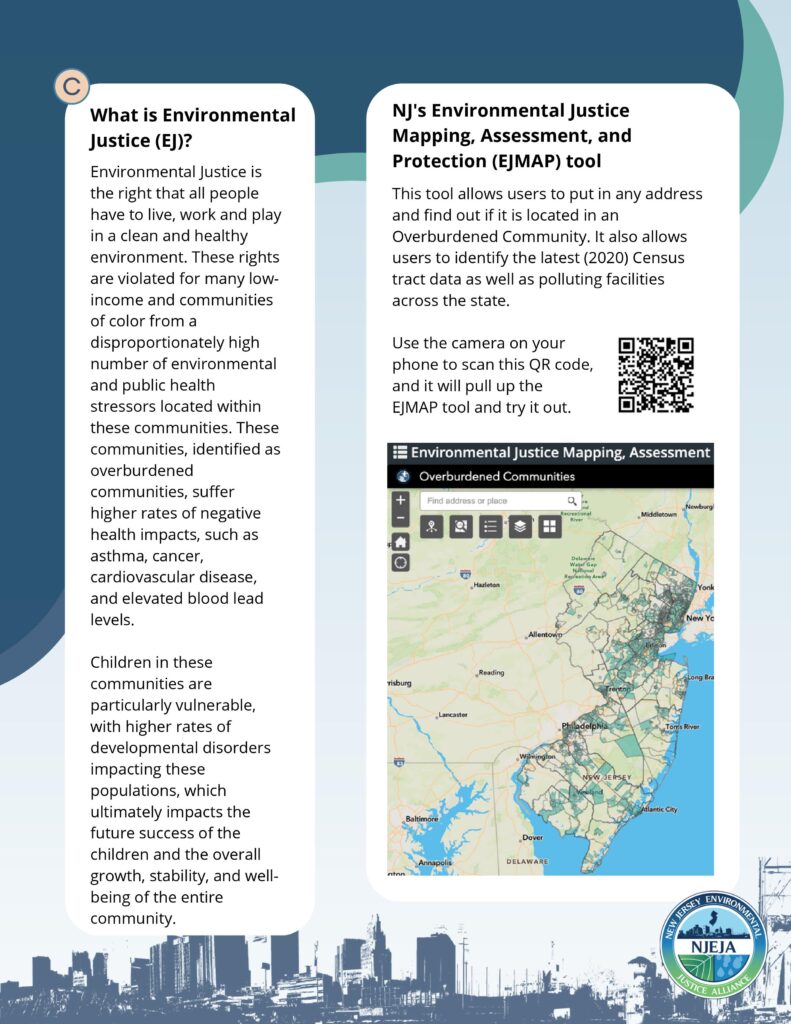

The result was legislation with key cumulative impact provisions. The law gave the state’s Department of Environmental Protection a mandate to deny permits for certain types of facilities like incinerators and sewage treatment plants seeking to locate in areas already burdened by pollution. It also required businesses to perform a cumulative impact analysis for new projects or expansions and gave the public more opportunities to influence permit applications.

Jonathon J. Smith, an attorney with the nonprofit Earthjustice, said demographic information, including race, income, and limited English proficiency, was used to help define an “overburdened” community.

And industry was barred under the law from using the promise of jobs as a reason to put a polluting facility in an overburdened community.

This last piece gets at a common practice in Michigan. For example, Stellantis used jobs to make the case for expanding its polluting facilities on Detroit’s east side. This project received$400 million in tax incentives and at least 12 odor violations since it opened in June 2021.

After New Jersey’s law was passed, Miles said her group worked to prevent industry from undermining the legislation and ensuring residents were available to influence the new rules when regulators put them together. However, New Jersey only began enforcing the law in April 2023 and Smith said the state will have to wait and see how much regulators are “taking it to heart”.

How Michigan could get it done

Trent Wolf, who recently served as the senior advisor to Michigan House Majority Floor Leader Abraham Aiyash (D-Hamtramck), told Planet Detroit that Aiyash and State Sen. Stephanie Chang (D-Detroit) are crafting cumulative impact legislation that can stand up to litigation or constitutional challenges.

In the wake of the Supreme Court’s decision to end race-based affirmative action in college admissions, environmental justice laws that use race as a criterion for defining an overburdened community could be open to legal challenges.

This ruling may have prompted the Environmental Protection Agency to drop a civil rights complaint into Louisiana’s permitting of industries in a heavily polluted area known as “cancer alley”.

Nick Schroeck, an environmental law expert at Detroit Mercy School of Law, said state programs that incorporate race as a factor in decision-making are less vulnerable to challenges than federal ones, although the language still needs to be drafted carefully.

Wolf said the White House’s Justice40 program, which seeks to direct 40 percent of federal climate-related funding to disadvantaged communities, could also provide a template for crafting a bill. This program excluded race when defining target areas, using other criteria as a proxy for disadvantaged communities of color. However, the screening tool used by the programs has had only mixed success in identifying these areas so far.

Previously, Michigan advocates have said the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy (EGLE) already has the power under Rule 901 and Rule 228 to consider cumulative impacts, at least from air pollution, and deny permits.

EGLE spokesperson Hugh McDiarmid said the powers provided by these rules were limited and that the agency’s air quality division “does not have the ability to do cumulative impact analysis incorporating all ways a person may be exposed to pollutants [but that] the program is designed to minimize potential health impacts of the air emissions from facilities on nearby residents.”

In Michigan, the first step toward creating a law that explicitly requires the agency to consider cumulative impacts may be engaging with impacted communities to raise awareness and get input on proposed legislation.

“For this legislation to move, it’s going to take a lot of work at the grassroots level of getting people engaged and understanding that legislation like this can have a deep impact in their community,” Wolf said. “This is a relatively new concept.”

Wolf also believes there’s the potential for urban advocates to build a coalition with rural people dealing with factory farms and facilities like chemical recycling centers and battery plants.

Pam Taylor, a farm owner in rural Lenawee County who leads the water testing program for the nonprofit Environmentally Concerned Citizens of Southeast Michigan, has been working for decades to address water quality problems created by the manure-laden discharge from industrial livestock farms. This pollution has contributed to potentially life-threatening toxic algal blooms downstream, like the 2014 Lake Erie bloom that shut down Toledo’s drinking water supply for several days.

In the past, Taylor has helped lead tours with the Sierra Club to highlight toxic industries in Detroit and Lenawee County, showing the public and mental health problems that occur when industry concentrates in certain areas.

Taylor said her sparsely populated community roughly 60 miles southwest of Detroit resembles other areas where scarce jobs and poverty drive people to work in industries that may compromise their health.

“There aren’t that many jobs, so people end up working for these big factory farms even though they hate it,” she said. “It’s basically a captured community, just like a mining community would be Appalachia.”

Taylor said a cumulative impact bill would reduce the impact of these farms on local waterways and protect groundwater. She said that as waterways have become more polluted, communities have turned to groundwater for drinking water, a resource threatened by water-hungry industrial farms.

“A cumulative impact bill would be wonderful,” Taylor said. “It would reduce the chance of so many of these farms being crammed together in one area.”

Pushback from industry

Michigan’s powerful industrial lobby, including automakers, utilities, and chemical companies, will likely fight against a cumulative impact bill that could add new business costs.

Mike Alaimo, director of environmental and energy affairs at the Michigan Chamber of Commerce, said cumulative impact laws would add new requirements for businesses that could hurt job creation and get in the way of rebuilding the state’s aging infrastructure.

“Cumulative impacts is kind of this whole new bureaucratic layer that would function on top of an already challenging and burdensome system,” he said. “Adding more burden, just adding more regulatory costs, will simply drive businesses away.”

He said these costs could undermine technology like carbon capture, which could be used to reduce emissions from fossil fuel power plants. That technology has been challenged by environmental advocates for its potential to increase non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions like nitrogen oxides and particulate matter as well as creating possible safety issues.

And if investment is pushed away from areas of concentrated industry, Alaimo said it could lead to developing greenfield areas instead of cleaning up contamination and redeveloping brownfield sites.

Schroeck said Michiganders have good reasons to support a cumulative impact law, even if they feel relatively protected from pollution. He said the transparency and cumulative impact assessments offered by a law like New Jersey’s could shed light on pollution issues residents may not be aware of, helping influence statewide permitting and protecting public health.

“I don’t think any of us are really safe,” Schroeck said. “To the extent that we can provide more data and more transparency, I think that will help the public at large to understand the benefits and also the costs of the way that we have been doing business.”

He adds that a healthier population is better for everyone, lowering healthcare costs and insurance rates. But Schroeck said that legislation could be stymied by a lack of knowledge among lawmakers and residents about the health impacts from pollution and the culture war framing of environmental justice that he said paints the issue as “a liberal pet project.”

Lawmakers also have a poor record of being proactive with environmental legislation, Schroeck said.

“We’re much better at, like looking backwards, coming up with cleanup standards and things, than we are at actually preventing harm in the first place,” he said.

He agrees with Landrum in southwest Detroit that more summers with wildfire smoke could create renewed urgency to manage air pollution as much as possible, changing the political calculus around cumulative impacts.

For now, Landrum says environmental advocates need to keep raising the issue until an opportune moment arrives to pass a bill like what happened in New Jersey.

“The intention is to keep putting it out there,” she said.