In These Times, Feb. 19, 2014

By Sarah Jaffee

[At Port Newark, the N.J. Environmental Justice Alliance is working with a coalition of labor and community groups to protect workers, reduce pollution, and provide more benefits to the City of Newark. –Editor]

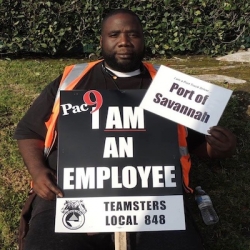

“Everyone that’s involved in container hauling is making money,” says Albert Dantes, a port truck driver at the Port of Savannah, Georgia. Everyone, that is, but Dantes and his colleagues, who spoke to me after an organizing meeting just off the highway on which they haul the goods that come in and out of the fourth-largest container port in the country.

The port brings in close to $16 billion per year, but the drivers only see a tiny bit of that money. This is in large part because they’re “misclassified” as independent contractors, driver Gerald Spaulding says—which lets the bosses at the various port trucking companies push off operating costs onto the drivers. These may include gas, repairs and the lease or payment for the truck itself. “All the expenses come out of your pocket,” says Dantes, noting that the gas cost alone per load is usually about half of what the driver is paid for the load. “If you lose a tire, you pay for it. [And] you just ran for free.”

A new report, The Big Rig Overhaul: Restoring Middle Class Jobs at America’s Ports Through Labor Law Enforcement, published by the National Employment Law Project, Change to Win Strategic Organizing Center and the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy, backs up what the drivers are saying. It estimates that some 49,000 of the country’s 75,000 port truckers are wrongly classified as independent contractors, and it calculates that that misclassification costs state and federal governments more than $563 million in lost tax revenue, and costs drivers in the state of California alone between $787 to $998 million in stolen wages.

The report analyzed more than 30 official government decisions since 2011 regarding the employment status of port truckers, and found that state and federal courts and agencies “overwhelmingly” conclude that the drivers are employees, not independent contractors. Only in one case, in Washington state, did an agency find that a driver was properly classified as an independent contractor. That means, the report says, that port trucking companies “are violating a host of state and federal labor and tax laws, including provisions related to wage and hour standards, income taxes, unemployment insurance, organizing, collective bargaining, and workers’ compensation.”

That confirms the findings of an earlier report put out in 2010 by NELP and Change to Win, The Big Rig: Poverty, Pollution and the Misclassification of Truck Drivers at America’s Ports, which found that median net earnings before taxes were $35,000 for employee drivers and only $28,783 for contractors, and contractors were two-and-a-half times less likely than employee drivers to have health insurance and three times less likely to have retirement benefits. To determine just how much misclassification costs individual workers, the new report looks at damages awarded in cases like Romeo Garcia v. Seacon Logix, Inc., where four drivers received a total of $107,803 in compensation after a court ruled they had been misclassified as contractors. The drivers had little voice in their job classification: All Spanish-speakers, they signed leases in English with the company for their trucks. Insurance was then deducted from their paychecks, as well as gas, repairs and registration fees. The hearing officer from California’s Division of Labor Standards Enforcement (DLSE) said in his decision, “The formation of independent contractor agreements signed by its drivers can be and often is a subterfuge to avoid paying payroll and income taxes.” A Los Angeles Superior Court judge, ruling on an appeal, said, “I am a believer in free markets. This was not a free and open market.”

And it’s not just California. In New Jersey, a disability claim from a driver prompted the state’s labor department to audit port trucking company Proud 2 Haul. The New Jersey Department of Labor found that by misclassifying workers as contractors, between 2007 and 2009 the company had evaded $127,723.49 in unemployment insurance and temporary disability contributions. The U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) determined that Proud 2 Haul’s drivers qualified as employees because of the control exercised over them—through truck leases and company rules—and the fact that they had no opportunity to offer their services elsewhere.

Even the Internal Revenue Service, applying the most stringent legal standard, according to the report, has found drivers to be employees, saying that contracts signed by drivers that called them independent contractors were not proof that they were, in fact, independent.

As I’ve written, deregulation of the port trucking industry was supposed to open up the ports to women and drivers of color, granting drivers like Dantes more access to good jobs. Making them “independent contractors” was intended to allow them the freedom to be their own bosses, driving their own trucks and choosing which company to work for. What’s actually happened, according to many of the lawsuits cited in The Big Rig Overhaul, is that drivers are no more free than they ever were—they’re required to show up on time, obey strict rules, in some cases take drug tests, and often lease a truck from their employer. In other words, they’re treated just as they were when the drivers were employees, except they’re bearing all the costs of their work.

And it’s not just port truckers who face this problem, the report points out. Rather, the truckers epitomize the state of labor in the U.S. over the past few decades:

“Since the mid-1970s, American workers have increasingly found themselves in uncertain, contingent employment relationships. Whole industries, such as warehousing, have been reconfigured to shift business costs onto individual workers, taxpayers, and local communities. Powerful companies have moved core operations into nebulous networks of undercapitalized subcontractors, both domestic and overseas. And large numbers of workers find themselves beyond the reach of such core labor protections as a minimum wage, unemployment insurance, and Social Security.”

The good news from this report is that there’s a lot that can be done simply by enforcing existing laws. Or, as Spaulding says, “We know what’s going on, but we don’t have anybody policing what’s taking place, administration-wise.”

The authors call for several actions in order to improve the effectiveness of state and federal enforcement agencies—among them, of course, increasing funding to enforcement agencies. They also encourage agencies to coordinate on the state and federal level, so that in states like California where state law is stronger, state agencies can do the work, while in places like Georgia, the federal DOL should step in. They also stress the need for stronger penalties for employers who retaliate against employees who speak out.

Several state legislatures have considered proposals that would strengthen protections for the port drivers, the report notes. New Jersey’s legislature even passed a bill in 2013 that would ensure drivers are treated as employees, but it was vetoed by Republican Gov. Chris Christie.

On the federal level, several pending pieces of legislation could help drivers and other misclassified workers. One of those is thePayroll Fraud Prevention Act of 2013, which would amend the Fair Labor Standards Act to require employers to notify workers of their employment status—whether contractor or employee. If the notification requirement were violated, workers would be assumed to be employees. This would clarify for the drivers what their rights are, and make it harder for employers to classify them one way and treat them another—employers who violate these rules would face civil penalties. Senator Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio), a sponsor of the bill, tells In These Times, “When unscrupulous employers misclassify their employees, they don’t pay unemployment insurance taxes or offer health insurance, pass along costs to taxpayers, and undermine their competitors who play by the rules.”

The drivers, however, aren’t waiting for legislation. Many of the cases studied in the report are class-action cases brought by workers who are organizing among themselves, some with the Teamsters union (a member of the Change to Win federation that put out this report).

Savannah port trucker Carol Cauley tells In These Times that after a trip to California to support striking port workers in November, she realized that the issues at the ports really are the same across the country. And that makes her and the other Savannah drivers want to be part of a national movement.

Such a movement could be a powerful thing, as the outsourcing that’s shipped American jobs overseas has required the labor of low-paid port truckers at home to function as well. Dantes notes, “If we stop [work], in three days every store would be empty, we could shut down every Walmart. There’d be nothing. No fuel would be moved because trucks move gas, medicine, everything that runs America is carried on a truck.”

SARAH JAFFE

Sarah Jaffe is a staff writer at In These Times and the co-host of Dissent magazine’s Belabored podcast. Her writings on labor, social movements, gender, media, and student debt have been published in The Atlantic, The Nation, The American Prospect, AlterNet, and many other publications, and she is a regular commentator for radio and television. You can follow her on Twitter @sarahljaffe.