NY Times, July 16, 2013

By Ekow N. Yankah

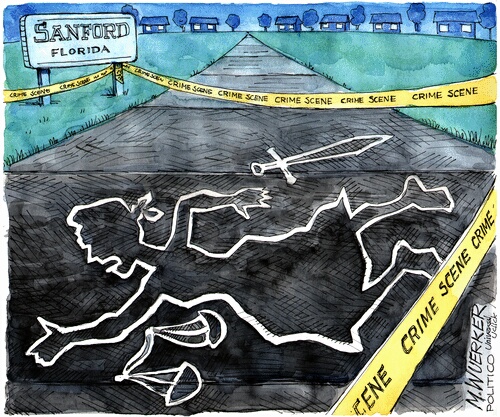

The Trayvon Martin verdict is frustrating, fracturing, angering and predictable. More than anything, for many of us, it is exhausting. Exhausting because nothing could bring back our lost child, exhausting because the verdict, which should have felt shocking, arrived with the inevitability that black Americans know too well when criminal law announces that they are worth less than other Americans.

Lawyers on both sides argued repeatedly that this case was never about race, but only whether prosecutors proved beyond a reasonable doubt that George Zimmerman was not simply defending himself when he shot Mr. Martin. And, indeed, race was only whispered in the incomplete invocation that Mr. Zimmerman had “profiled” Mr. Martin. But what this case reveals in its overall shape is precisely what the law is unable to see in its narrow focus on the details.

The anger felt by so many African-Americans speaks to the simplest of truths: that race and law cannot be cleanly separated. We are tired of hearing that race is a conversation for another day. We are tired of pretending that “reasonable doubt” is not, in every sense of the word, colored.

Every step Mr. Martin took toward the end of his too-short life was defined by his race. I do not have to believe that Mr. Zimmerman is a hate-filled racist to recognize that he would probably not even have noticed Mr. Martin if he had been a casually dressed white teenager.

But because Mr. Martin was one of those “punks” who “always get away,” as Mr. Zimmerman characterized him in a call to the police, Mr. Zimmerman felt he was justified in following him. After all, a young black man matched the criminal descriptions, not just in local police reports, but in those most firmly lodged in Mr. Zimmerman’s imagination.

Whether the law judges Trayvon Martin’s behavior to be reasonable is also deeply colored by race. Imagine that a militant black man, with a history of race-based suspicion and a loaded gun, followed an unarmed white teenager around his neighborhood. The young man is scared, and runs through the streets trying to get away. Unable to elude his black stalker and, perhaps, feeling cornered, he finally holds his ground — only to be shot at point-blank range after a confrontation.

Would we throw up our hands, unable to conclude what really happened? Would we struggle to find a reasonable doubt about whether the shooter acted in self-defense? A young, white Trayvon Martin would unquestionably be said to have behaved reasonably, while it is unimaginable that a militant, black George Zimmerman would not be viewed as the legal aggressor, and thus guilty of at least manslaughter.

This is about more than one case. Our reasons for presuming, profiling and acting are always deeply racialized, and the Zimmerman trial, in ignoring that, left those reasons unexplored and unrefuted.

What is reasonable to do, especially in the dark of night, is defined by preconceived social roles that paint young black men as potential criminals and predators. Black men, the narrative dictates, are dangerous, to be watched and put down at the first false move. This pain is one all black men know; putting away the tie you wear to the office means peeling off the assumption that you are owed equal respect. Mr. Martin’s hoodie struck the deepest chord because we know that daring to wear jeans and a hooded sweatshirt too often means that the police or other citizens are judged to be reasonable in fearing you.

We know this, yet every time a case like this offers a chance for the country to tackle the evil of racial discrimination in our criminal law, courts have deliberately silenced our ability to expose it. The Supreme Court has held that even if your race is what makes your actions suspicious to the police, their suspicions are reasonable so long as an officer can later construct a race-neutral narrative.

Likewise, our death penalty cases have long presaged the Zimmerman verdict, exposing how racial disparities, which make a white life more valuable, do not undermine the constitutionality of the death sentence. And even the most casual observer recognizes the painful racial disparities in our prison population — the new Jim Crow, in the account of the legal scholar Michelle Alexander. Our prisons are full of young, black men for whom guilty beyond a reasonable doubt was easy enough to reach.

There is no quick answer for the historical use of our criminal law to reinforce and then punish social stereotypes. But pretending that reasonable doubt is a value-free clinical term, as so many people did so readily in the Zimmerman case, only insulates injustice in plain sight.

Without an honest jurisprudence that is brave enough to tackle the way race infuses our criminal law, Trayvon Martin’s voice will be silenced again.

What would such a jurisprudence look like? The Supreme Court could hold, for example, that the unjustified use of race by the police in determining “reasonable suspicion” constituted an unreasonable stop, tainting captured evidence. Likewise, in the same way we have started to attack racial disparities in other areas of criminal law, we could consider it a violation of someone’s constitutional rights if, controlling for all else, his race was what determined whether the state executed him.

I can imagine a jurisprudence that at least begins to use racial disparities as a tool to question the constitutionality of criminal punishment. And above all, I can imagine a jurisprudence that does not pretend, as lawyers for both sides (but no one else) did in the Zimmerman case, that doubts have no color.

Ekow N. Yankah a professor at the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law at Yeshiva University.