A New Electricity Divide Threatens to Leave the Less Privileged Behind

Climate Progress (July 15, 2013)

by Jeff Spross

Electricity is undergoing a massive jump forward in technological sophistication — just like telephone communications, the internet, wireless and broadband access have. And while this advancement brings benefits, it also threatens to leave poorer and less privileged Americans behind. That’s the take away of a new paper by Richard Caperton and Mari Hernandez at the Center for American Progress, which also offers a few ideas to get put ahead of the problem.

The first problem is that providing access to new technologies of this sort requires a great deal of costly infrastructure. And from the pure self-interested analysis of actors on the free market, the costs of extending that access to lower-income customers or geographically remote ones exceeds the benefits.

The second problem is that as new technologies become available — in this case, residential solar, energy efficient infrastructure, better battery storage, and other ways to save or self-generate power — it’s the economically privileged that first take advantage of them. That allows them to disconnect from the old technology — in this case, the established electrical grid — first, leaving less privileged customers behind to fund an increasingly expensive infrastructure.

As the paper notes, telephone communication provides an example of what happens next: From 2008 to 2012, wireless-only subscribers jumped 77 percent to encompass 35.8 percent of the American population, while landline-only customers dropped from 17.4 percent to 9.4 percent. Since then, some California customers have seen landline rate hikes of up to 50 percent over the past two years alone. The resulting digital divide, according to a Pew Survey, has left households earning less than $30,000 per year 35 percent less likely to have Internet access than households earning $75,000 or more.

To avoid a similar class divide emerging as solar generation, smart grid technology, and other advancements continue to disrupt the traditional electricity grid, the paper recommends a number of policies:

Repurpose existing electric service programs. The federally funded Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP) already provides home energy-bill assistance to low-income households. It could be expanded to include renewable-energy funding. The Rural Utilities Service (RUS) is another federal program that provides financing for electric systems across rural America. It’s in the process of approving a new program providing loans for households to install distributed generation and energy-efficiency tools. It could also be expanded to address any future electrical divide.

Bring regulatory changes to the electric industry. This would treat new energy and grid technology companies the same way as the utilities that previously served the same customers. This would come with practical problems, so an new version of the approach Duke Energy is trying out would mandate that existing utilities offer the technologies that allow customers to disconnect from the grid.

Give companies incentives to address the electrical divide. This could be done through the tax code. For example, a tax credit could encourage distributed generation companies to put solar panels on low-income households. As the paper notes, existing tax incentives for renewable energy have been a tremendous success.

Create a federally owned provider of new energy resources. Decades ago, the U.S. government established the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) to bring electricity to those aforementioned Americans the free market was leaving behind. The government could do the same thing for the emerging market in renewable energy and grid technologies.

As the paper notes, just because the free market, when left to its own devices, would fail to provide universal access does not mean such reticence is best for the economy as a whole. The benefits to economic and job growth of providing universal access are big but often overlooked. Access to these new electricity technologies would bring efficient lighting and cooking options, new opportunities to work, communication tools, educational resources, modern health care services, and increased productivity and competitiveness to tens of millions of poor and underprivileged Americans. It would also help build a broad middle class and customer based for the more advanced products — from appliances to modern computing and communications tools — that are still manufactured in the U.S.

Hunger Games, U.S.A.

New York Times, July 14, 2013

By Paul Krugman

Something terrible has happened to the soul of the Republican Party. We’ve gone beyond bad economic doctrine. We’ve even gone beyond selfishness and special interests. At this point we’re talking about a state of mind that takes positive glee in inflicting further suffering on the already miserable.

The occasion for these observations is, as you may have guessed, the monstrous farm bill the House passed last week.

For decades, farm bills have had two major pieces. One piece offers subsidies to farmers; the other offers nutritional aid to Americans in distress, mainly in the form of food stamps (these days officially known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP).

Long ago, when subsidies helped many poor farmers, you could defend the whole package as a form of support for those in need. Over the years, however, the two pieces diverged. Farm subsidies became a fraud-ridden program that mainly benefits corporations and wealthy individuals. Meanwhile food stamps became a crucial part of the social safety net.

So House Republicans voted to maintain farm subsidies — at a higher level than either the Senate or the White House proposed — while completely eliminating food stamps from the bill.

To fully appreciate what just went down, listen to the rhetoric conservatives often use to justify eliminating safety-net programs. It goes something like this: “You’re personally free to help the poor. But the government has no right to take people’s money” — frequently, at this point, they add the words “at the point of a gun” — “and force them to give it to the poor.”

It is, however, apparently perfectly O.K. to take people’s money at the point of a gun and force them to give it to agribusinesses and the wealthy.

Now, some enemies of food stamps don’t quote libertarian philosophy; they quote the Bible instead. Representative Stephen Fincher of Tennessee, for example, cited the New Testament: “The one who is unwilling to work shall not eat.” Sure enough, it turns out that Mr. Fincher has personally received millions in farm subsidies.

Given this awesome double standard — I don’t think the word “hypocrisy” does it justice — it seems almost anti-climactic to talk about facts and figures. But I guess we must.

So: Food stamp usage has indeed soared in recent years, with the percentage of the population receiving stamps rising from 8.7 in 2007 to 15.2 in the most recent data. There is, however, no mystery here. SNAP is supposed to help families in distress, and lately a lot of families have been in distress.

In fact, SNAP usage tends to track broad measures of unemployment, like U6, which includes the underemployed and workers who have temporarily given up active job search. And U6 more than doubled in the crisis, from about 8 percent before the Great Recession to 17 percent in early 2010. It’s true that broad unemployment has since declined slightly, while food stamp numbers have continued to rise — but there’s normally some lag in the relationship, and it’s probably also true that some families have been forced to take food stamps by sharp cuts in unemployment benefits.

What about the theory, common on the right, that it’s the other way around — that we have so much unemployment thanks to government programs that, in effect, pay people not to work? (Soup kitchens caused the Great Depression!) The basic answer is, you have to be kidding. Do you really believe that Americans are living lives of leisure on $134 a month, the average SNAP benefit?

Still, let’s pretend to take this seriously. If employment is down because government aid is inducing people to stay home, reducing the labor force, then the law of supply and demand should apply: withdrawing all those workers should be causing labor shortages and rising wages, especially among the low-paid workers most likely to receive aid. In reality, of course, wages are stagnant or declining — and that’s especially true for the groups that benefit most from food stamps.

So what’s going on here? Is it just racism? No doubt the old racist canards — like Ronald Reagan’s image of the “strapping young buck” using food stamps to buy a T-bone steak — still have some traction. But these days almost half of food stamp recipients are non-Hispanic whites; in Tennessee, home of the Bible-quoting Mr. Fincher, the number is 63 percent. So it’s not all about race.

What is it about, then? Somehow, one of our nation’s two great parties has become infected by an almost pathological meanspiritedness, a contempt for what CNBC’s Rick Santelli, in the famous rant that launched the Tea Party, called “losers.” If you’re an American, and you’re down on your luck, these people don’t want to help; they want to give you an extra kick. I don’t fully understand it, but it’s a terrible thing to behold.

© 2013 The New York Times

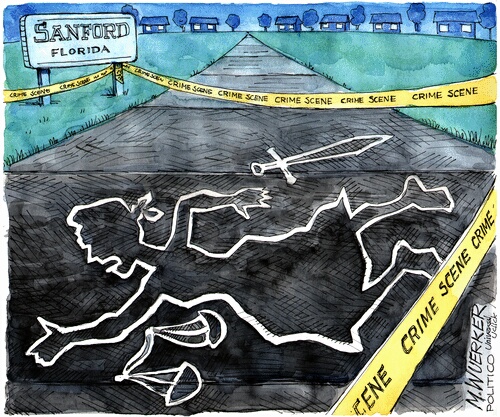

Prayer, Anger and Protests Greet Verdict in Florida Case

N.Y. Times July 14, 2013

Protests Follow Zimmerman Acquittal

The fallout over the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of Trayvon Martin was felt across the country on Sunday.

By Adam Nagourney

The acquittal of George Zimmerman in the death of Trayvon Martin reverberated from church pulpits to street protests across the country on Sunday in a renewed debate about race, crime and how the American justice system handled a racially polarizing killing of a young black man walking in a quiet neighborhood in Florida.

Lawmakers, members of the clergy and demonstrators who assembled in parks and squares on a hot July day described the verdict by the six-person jury as evidence of a persistent racism that afflicts the nation five years after it elected its first African-American president.

“Trayvon Benjamin Martin is dead because he and other black boys and men like him are seen not as a person but a problem,” the Rev. Dr. Raphael G. Warnock, the senior pastor at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, told a congregation once led by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Dr. Warnock noted that the verdict came less than a month after the Supreme Court voted 5 to 4 to void a provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. “The last few weeks have been pivotal to the consciousness of black America,” he said in an interview after services. “Black men have been stigmatized.”

Mr. Zimmerman, 29, a neighborhood watch volunteer, had faced charges of second-degree murder and manslaughter — and the prospect of decades in jail, if convicted — stemming from his fatal shooting of Mr. Martin, 17, on the night of Feb. 26, 2012, in Sanford, a modest Central Florida city. Late Saturday, he was acquitted of all charges by the jurors, all of them women and none black, who had deliberated more than 16 hours over two days.

President Obama, calling Mr. Martin’s death a tragedy, urged Americans on Sunday to respect the rule of law, and the Justice Department said it would review the case to determine if it should consider a federal prosecution.

As dusk fell in New York, a modest rally that had begun hours earlier in Union Square grew to a crowd of thousands that snaked through Midtown Manhattan toward Times Square in an unplanned parade. Onlookers used cellphones to snap pictures of the chanting protesters and their escort by dozens of police cars and scores of officers on foot. Hundreds of bystanders left the sidewalks to join the peaceful demonstration, which brought traffic to a standstill.

In Sanford, the Rev. Valarie J. Houston drew shouts of support and outrage at Allen Chapel A.M.E. as she denounced “the racism and the injustice that pollute the air in America.”

“Lord, I thank you for sending Trayvon to reveal the injustices, God, that live in Sanford,” she said.

Mr. Zimmerman and his supporters dismissed race as a factor in the death of Mr. Martin. The defense team argued that Mr. Zimmerman had acted in self-defense as the 17-year-old slammed Mr. Zimmerman’s head on a sidewalk. Florida law explicitly gives civilians the power to take extraordinary steps to defend themselves when they feel that their lives are in danger.

Mr. Zimmerman’s brother, Robert, told National Public Radio that race was not a factor in the case, adding: “I never have a moment where I think that my brother may have been wrong to shoot. He used the sidewalk against my brother’s head.”

Mr. Obama, who had said shortly after Mr. Martin was killed that if he had a son, “he’d look like Trayvon,” urged the nation to accept the verdict.

“The death of Trayvon Martin was a tragedy,” Mr. Obama said in a statement. ”Not just for his family, or for any one community, but for America. I know this case has elicited strong passions. And in the wake of the verdict, I know those passions may be running even higher. But we are a nation of laws, and a jury has spoken.”

Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg of New York, one of the country’s leading advocates of gun control, said the death of Mr. Martin would continue to drive his efforts. “Sadly, all the facts in this tragic case will probably never be known,” he said. “But one fact has long been crystal clear: ‘Shoot first’ laws like those in Florida can inspire dangerous vigilantism and protect those who act recklessly with guns.”

The reactions to the verdict suggested that racial relations remained polarized in many parts of this country, particularly regarding the American justice system and the police.

“I pretty well knew that Mr. Zimmerman was going to be let free, because if justice was blind of colors, why wasn’t there any minorities on the jury?” said Willie Pettus, 57, of Richmond, Va.

Maxine McCrey, attending services at Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York, said the verdict was a reminder of the failure of the justice system. “There’s no justice for black people,” she said. “Profiling and targeting our black men has not stopped.”

Ms. McCrey dabbed at her eyes as she recalled the moment she learned of the verdict. “I cried,” she said. “And I am still crying.”

Many blacks, and some whites, questioned whether Mr. Zimmerman, who is part Hispanic, would have been acquitted if he were black and Mr. Martin were white.

“He would have been in jail already,” Leona Ellzy, 18, said as she visited a monument to Mr. Martin in Sanford. “The black man would have been in prison for killing a white child.”

Jeff Fard, a community organizer in a black neighborhood in Denver, said Mr. Martin would be alive today if he were not black. “If the roles were reversed, Trayvon would have been instantly arrested and, by now, convicted,” he said. “Those are realities that we have to accept.”

But even race’s role in the case became a matter of a debate. One of Mr. Zimmerman’s lawyers, Mark O’Mara, said he also thought the outcome would have been different if his client were black — but for reasons entirely different from those suggested by people like Mr. Fard.

“He never would have been charged with a crime,” Mr. O’Mara said.

“This became a focus for a civil rights event, which again is a wonderful event to have,” he said. “But they decided that George Zimmerman would be the person who they were to blame and sort of use as the creation of a civil rights violation, none of which was borne out by the facts. The facts that night were not borne out that he acted in a racial way.”

In Atlanta, Tommy Keith, 62, a white retired Cadillac salesman, rejected any contention that this was anything more than a failed murder case presented by the state. “The state’s got to prove their case, O.K.?” he said. “They didn’t. Stand Your Ground law is acceptable with me, and these protests are more racial than anything else. In my opinion, it’s not a racial thing.”

Within moments of the announcement of the verdict Saturday night and continuing through Sunday, demonstrations, some planned and some impromptu, arose in neighborhoods in Chicago, Los Angeles, Washington, New York and Atlanta. There were no reports of serious violence or arrests as the day went on, a contrast with the riots that swept Los Angeles after the verdict in another race-tinged case, the 1992 acquittal of white Los Angeles police officers in the beating of Rodney King, a black construction worker.

In downtown Oakland, dozens of protesters filled the streets to denounce the verdict shortly after it was announced. Some of the protesters set fire to trash cans, broke the windows of businesses and damaged police patrol cars.

About 40 people in Atlanta, carrying sodas and Skittles to underscore the errand to a store that Mr. Martin was completing when he was shot, marched to Woodruff Park on Saturday night. In Washington, about 250 marchers protested the verdict late Saturday and early Sunday as police cruisers trailed them.

A few hundred protesters gathered at a rally in downtown Chicago on Sunday, some wearing signs showing Mr. Martin wearing a hoodie.

“I’m heartbroken, but it didn’t surprise me,” said Velma Henderson, 65, a retired state employee who lives in a southern suburb of Chicago. “The system is screwed. It’s a racist system, and it’s not designed for African-Americans.”

A similar sense of resignation flowed through St. Sabina, a Catholic church on the South Side of Chicago, where many parishioners are black. They gathered in the sanctuary holding signs that read, “Trayvon Martin murdered again by INjustice system.”

“Like many of you, I’m angered, I’m disappointed, I’m disgusted,” said the Rev. Michael Pfleger, who is white, told his congregation at St. Sabina. “And yet like many of you, I’m not shocked. ’Cause unfortunately, this is the America that we know all too well. Yesterday, we watched the justice system fail miserably again.”

As blacks and whites struggled with the racial implications of the debate, many called for prayer and peace and urged that there be no escalation of violence.

“My heart is heavy,” said Milton Felton, a cousin of Mr. Martin’s, outside Antioch Missionary Baptist Church in Miami Gardens, Fla., where members of the family had gathered. “But that’s our justice system. Let’s be peaceful about it.”

At Abyssinian Baptist Church in Harlem, parishioners seemed stricken by what many described as a reminder of how far the nation still needed to go to resolve its racial differences. “I felt he was going to get off,” said Helen Corley, attending services there. “He knew he could do it and get away with it.”

“It crushed my spirit,” she said.

Reporting was contributed by Michael Schwirtz, Michaelle Bond and Whitney Richardson from New York; Cara Buckley from Sanford, Fla.; Kim Severson and Alan Blinder from Atlanta; Monica Davey and Steven Yaccino from Chicago; Jack Healy from Denver; Ian Lovett from Los Angeles; Nick Madigan from Miami; Jon Hurdle from Philadelphia; John Eligon from Kansas City, Mo.; Norimitsu Onishi from San Francisco; and Trip Gabriel from Washington.

Correction: July 14, 2013

An earlier version of this article misstated the given name of a pastor in Sanford, Fla. She is Valarie J. Houston, not Valerie. It also misstated the city where Jeff Fard is a community organizer. It is Denver, not Detroit.

© 2013 The New York Times