Vox, Apr. 22, 2014

By Brad Plumer

It was the early 1990s. Climate scientists had long known that humans were warming up the planet. But politicians were just beginning to grasp that it would take a huge coordinated effort to get nations to burn fewer fossil fuels and avoid sharp temperature increases in the decades ahead.

Those policymakers needed a common goal — a way to say, Here’s how bad things will get and This is what we need to do to stop it. And that posed a dilemma. No one could really agree on how much global warming was unacceptable. How high did the seas need to rise before we had a serious problem? How much heat was too much?

Around this time, an advisory council of scientists in Germany proposed a stunningly simple way to think about climate change. Look, they reasoned, human civilization hasn’t been around all that long. And for the last 13,000 years, Earth’s climate has fluctuated within a narrow band. So, to be on the safe side, we should prevent global average temperatures from rising more than 2° Celsius (or 3.6° Fahrenheit) above what they were just before the dawn of industrialization.

Critics grumbled that the 2°C limit seemed arbitrary or overly simplistic. But scientists were already compiling evidence that the risks of global warming became especially daunting somewhere above the 2°C threshold: rapid sea-level rise, the risk of crop failure, the collapse of coral reefs. And policymakers loved the idea of a simple, easily digestible target. So it stuck.

The idea that the world can stay below 2°C looks increasingly delusional

By 2009, nearly every government in the world had endorsed the 2°C limit — global warming beyond that level was deemed “dangerous.” And so, every year, the world’s leaders meet at UN climate conferences to discuss policies and emissions cuts that they hope will keep us below 2°C. Climate experts churn out endless papers on how we can adapt to 2°C of warming (or less).

Two decades later, there’s just one major problem with this picture. The idea that the world can stay below 2°C looks increasingly delusional.

Consider: the Earth’s average temperature has already risen 0.8°C since the 19th century. And if you look at the current rapid rise in global greenhouse-gas emissions, we’re on pace to blow past the 2°C limit by mid-century — and hit 4°C or more by the end. That’s well above anything once deemed “dangerous.”Getting back on track for 2°C would, at this point, entail the sort of drastic emissions cuts usually associated with economic calamities, like the collapse of the Soviet Union or the 2008 financial crisis. And we’d have to repeat those cuts for decades.

The climate community has been slow to concede defeat. Back in 2007, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change published a report noting that the world could stay below 2°C — but only if we started cutting emissions immediately. The years passed, countries did little, and emissions kept rising. So, just this month, the IPCC put out a new report saying, OK, not great, but we can still stay under 2°C. We just need to act more drastically and figure out some way to pull carbon dioxide back out of the atmosphere. (Never mind that we still don’t have the technology to do the latter.)

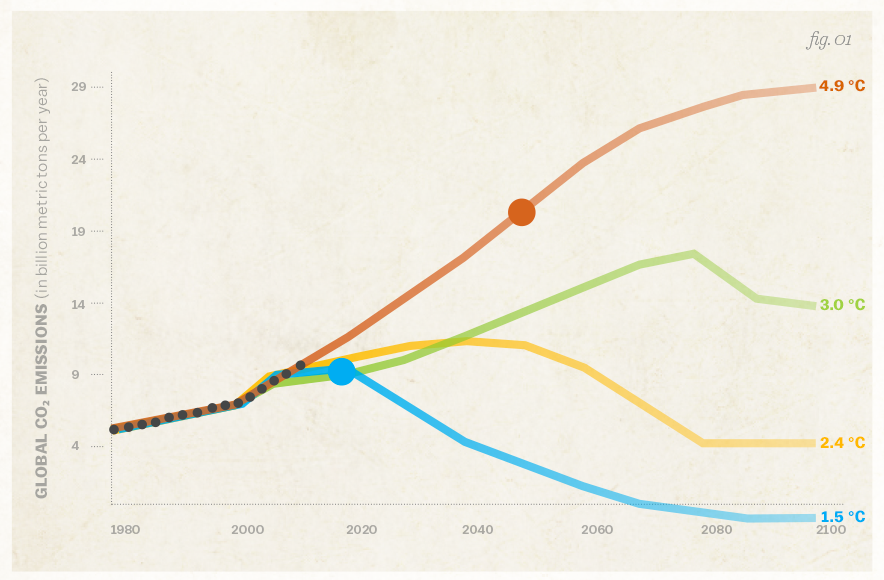

We’re on track for 4°C of global warming — and 2°C is increasingly unlikely

Predicted temperature increases under various emissions scenarios:

On our current course, the world will put enough carbon-dioxide in the atmosphere by mid-century to breach the 2°C target.

Emissions would need to decline dramatically (and then go negative) for a good shot at staying below 2°C.

- Historical emissions

- High emissions

Medium emissions - Low emissions

Extremely low emissions

“At some point, scientists will have to declare that it’s game over for the 2°C target,” says Oliver Geden, a climate policy analyst at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs. “But they haven’t yet. Because nobody knows what will happen if they call this thing off.” The 2°C target was one of the few things that everyone at global climate talks could agree on. If the goal turns out to be impossible, people might just stop trying altogether.

Recently, then, some scientists and policymakers have been taking a fresh look at whether the 2°C limit is still the best way to think about climate change. Is this simple goal actually making it harder to prepare for the warming that lies ahead? Is it time to consider other approaches to climate policy? And if 2°C really is so dangerous, what do we do when it’s out of reach?

The murky origins of the 2°C limit

Back in the 1970s, climate scientists understood that the carbon dioxide that humans had been emitting since the Industrial Revolution — from cars, power plants, factories — was intensifying the greenhouse effect that warms the planet. They also knew that man-made emissions were increasing each year as the global economy grew.

So how hot would it get? Early calculations suggested that if we doubled the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere over pre-industrial levels, the Earth would warm somewhere between 1.5°C and 4.5°C. In the decades since, scientists have amassed more evidence for this estimate of “climate sensitivity,” but they haven’t really narrowed the range.

The next step was to figure out how much warming humans could safely tolerate. There were a variety of ideas for defining “dangerous” interference with the Earth’s climate in the early 1990s. Maybe we should try to limit the rate of warming per decade, for instance.

Eventually, the 2°C limit won out — endorsed by, among others, a council of German scientists advising Angela Merkel, the nation’s environment minister at the time. Their thinking: human civilization had developed in a period when sea levels remained stable and agriculture could flourish. Staying within that bound — and preventing global average temperatures from rising more than 2°C — seemed like a reasonable rule of thumb.

“We said that, at the very least, it would be better not to depart from the conditions under which our species developed”

“We said that, at the very least, it would be better not to depart from the conditions under which our species developed,” recalls Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, one of the scientists on that German advisory panel who helped devise the 2°C limit. “Otherwise we’d be pushing the whole climate system outside the range we’ve adapted to.”

Over time, researchers gravitated toward this limit. An influential 2001 report from the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change detailed a number of reasons to worry about climate change: increased heat waves and storms, the threat of mass extinctions, severe economic losses. Many of these so-called “reasons of concern” were projected to get much worse as global warming climbed past 2°C.

Now, there are good arguments that the 2°C limit is arbitrary. Any limit would be. For instance, subsequent research has found that plenty of worrisome impacts actually happen well before we hit 2°C: Arctic sea ice could collapse, coral reefs could die off, tiny island nations like Tuvalu could get swallowed by the rising seas. Conversely, other worrisome changes, such as crop damage in the United States, might not happen until we go above the 2°C threshold. Deciding where to draw this line is a political judgment as much as a scientific one. (To put it another way, no climate scientist thinks we’ll be totally fine if we hit 1.9°C of warming but totally doomed if we hit 2.1°C.)

Economists, meanwhile, have often criticized the 2°C limit for not taking costs into account. After all, we don’t just burn oil, gas, and coal for fun. We use them to power our cars and homes and factories. And cutting back won’t be painless. William Nordhaus, an economist at Yale, has argued that we should aim for a temperature limit where the costs of reducing fossil fuels matches the climate benefits. In his book The Climate Casino, he pegs this limit at 2.5°C or possibly higher, depending on how easily we can switch to clean energy sources.

Still, despite the criticisms, the 2°C limit has maintained its dominant position for more than a decade — in part because it created an easy focal point for international negotiations. UN climate talks start by assuming the need to stay below 2°C and then work backward to hash out how each country should cut emissions. The European Union’s energy policies consistently reference this limit. The Obama administration’s upcoming rules to restrict carbon-dioxide emissions from US coal plants can be traced back to a pledge President Obama made in 2009 to help stay below 2°C.

That raises a question: what will happen if it becomes apparent that the 2°C limit is out of reach? Will we settle on a new limit? Or just give up altogether?

Here’s how climate experts often think about the 2°C limit. Estimates of climate sensitivity tell us that the Earth will eventually warm somewhere between 1.5°C and 4.5°C if we double the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere over pre-industrial levels. And we’re almost halfway to doubling.

So, if we want reasonable odds of staying below 2°C, there’s only so much more additional carbon dioxide we can put in the atmosphere. That’s our “carbon budget” — around 485 billion metric tons.

There’s not a lot of wiggle room left. Humans added the equivalent of 10 billion metric tons of carbon into the atmosphere in 2012, and that amount is rising every year, as fast-growing countries like China and India build new factories, drive new cars, and burn lots of fossil fuels. At current rates, the world will exhaust its carbon budget in roughly three decades, setting the stage for 2°C of warming. (If climate sensitivity turns out to be low, that only buys us an extra decade or so.)

If we want to stay within the budget and avoid 2°C, then, our annual emissions need to start declining each year. Older, dirtier coal plants would need to get replaced with cleaner wind or solar or nuclear plants, say. Or gas-guzzling SUVs would need to get replaced with new low-carbon electric cars. But the longer we put this off, the harder it gets — the carbon budget gets smaller, and there are more coal plants and SUVs to replace.

The longer we wait on cutting emissions, the harder it gets

If we want a reasonable shot at staying below 2°C, there’s only so much more carbon-dioxide we can load into the atmosphere. If the world had started back in 2005, emissions could have decreased gently each year. If we wait until, say, 2020, the cuts have to be much sharper to catch up.

By now, countries have delayed action for so long that the necessary emissions cuts will have to be extremely sharp. In April 2014, the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded that if we want to stay below the 2°C limit, global greenhouse-gas emissions would have to decline between 1.3 percent and 3.1 percent each year, on average, between 2010 and 2050.

“If you’re serious about 2°C, the rates of change are so significant, it begs the way we see the world”

To put that in perspective, global emissions declined by just 1 percent for a single year after the 2008 financial crisis, during a brutal recession when factories and buildings around the world were idling. We’d potentially have to triple that pace of cuts, and sustain it year after year.

Some climate experts are skeptical that countries can do this while maintaining their historical rates of economic growth. The fastest that any country has ever managed to decarbonize its economy without suffering a crushing recession was France, when it spent billions to scale up its nuclear program between 1980 and 1985. That was a gargantuan feat — emissions fell 4.8 percent per year — but the country only sustained it for a five-year stretch.

To stay within the 2°C budget, every country would have to keep up that pace for decades, decarbonizing not just power plants, but factories, and homes, and cars, and airplanes. That goes far beyond even the most ambitious climate proposals currently being considered, including Obama’s big plan to curb emissions from US coal plants.

“If you’re serious about 2°C, the rates of change are so significant that it begs the way we see the world. That’s what people aren’t prepared to embrace,” says Kevin Anderson, a climate scientist at the Tyndall Centre for Climate Research. “Essentially you’d have to start asking questions about our current society and how we develop and grow.”

Anderson, for one, has argued that wealthy countries may need to sacrifice economic growth, at least temporarily, to stay below 2°C. In December, the Tyndall Centre hosted a conference on “radical emissions reductions” that offered some eye-popping suggestions: Perhaps every adult in wealthy countries could get a personal “carbon budget” tracked through an electronic credit card. Once they hit their limit, no more vacations or road trips. Other attendees suggested shaming campaigns against celebrities with outsized homes and yachts.

Not everyone is ready to go radical. The IPCC’s latest report suggested that an ambitious push on clean energy might only put a modest dent in global economic growth rates (a mere 0.06 percentage points per year). That’s partly because the cost of solar and wind power has been dropping far faster than anyone expected.

But even when you account for that, the IPCC figured that staying below 2°C would depend on a series of long-shot maneuvers: all nations would need to act right this second, ramp up wind and solar and nuclear power massively, and figure out still-nascent technologies to capture and bury emissions from coal plants. Crucially, we’d also have to invent some method of pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere — something that may never work on a large scale.

If any of those assumptions falter, the IPCC noted, costs start rising. And, as the years go by and the world’s nations put off cutting emissions, the odds of staying below 2°C look vanishingly unlikely.

“Ten years ago, it was possible to model a path to 2°C without all these heroic assumptions,” says Peter Frumhoff of the Union of Concerned Scientists. “But because we’ve dallied for so long, that’s no longer true.” In February, Frumhoff co-authored a paper in Nature Climate Change arguing that policymakers need to take the prospect of breaching the 2°C limit far more seriously than they’re currently doing. Otherwise, we’ll find ourselves unprepared for what comes next.

If 2°C looks increasingly out of reach, then it’s worth looking at what happens if we blow past that and go to, say, 3°C or 4°C.

Four degrees (or 7.2° Fahrenheit) may not sound like much. But the world was only about 4°C to 7°C cooler, on average, during the last ice age, when large parts of Europe and the United States were covered by glaciers. The IPCC concluded that changing the world’s temperature in the opposite direction could bring similarly drastic changes, such as “substantial species extinctions,” or irreversibly destabilizing Greenland’s massive ice sheet.

In 2013, researchers with the World Bank took a look at the science on projected effects of 4°C warming and were appalled by what they found. A growing number of studies suggest that global food production could take a big hit under 3°C or 4°C of warming. Poorer countries like Bangladesh, Egypt, Vietnam, and parts of Africa could see large tracts of farmland made unusable by rising seas.

But what seemed to unnerve the authors of the World Bank report most was all of the stuff we don’t know. Most climate models currently make predictions in a linear fashion. That is, they basically assume that the impacts of 4°C of warming will be twice as bad as those of 2°C. But that might be wrong. Impacts may interact with each other in unpredictable ways. Current agriculture models, they noted, don’t have a good sense for what will happen to crops if heat waves, droughts, new pests and diseases all combine together.

“If we keep assuming we can stay below 2°C as a matter of course, then we aren’t being honest about the adaptation challenges”

Here’s an analogy that Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, who helped compile some of the research for the World Bank, likes to use. “Take the human body. If your temperature rises 2°C, you have a significant fever. If it rises 4°C or 6°C you can die. It’s not a linear change. You’re pushing a complex system outside the range it’s adapted to. And all our assessments indicate that once you do that, the system’s resilience gets stretched thin.”

Perhaps most significantly, the World Bank report wasn’t even sure if humanity could adapt to a 4°C world. At the moment, the large lender is helping poorer countries prepare for global warming by building seawalls, conducting crop research, and improving freshwater management. But, as an internal review found, most of these efforts are being done with relatively small temperature increases in mind. The bank wasn’t planning for 3°C or 4°C of global warming — because no one really knew what that might entail.

“[G]iven that uncertainty remains about the full nature and scale of impacts,” the report said, “there is also no certainty that adaptation to a 4°C world is possible.” And its conclusion was stark: “The projected 4°C warming simply must not be allowed to occur.”

Only very recently have scientists even started trying to fill in those gaps in knowledge. Here’s a telling anecdote: back in 2011, the European Commission put out a call for papers exploring the impacts of a 2°C rise in temperature. Two years later, the call went out for impacts of warming greater than 2°C. What was once unthinkable is quickly becoming thinkable.

“If we keep assuming we can stay below 2°C as a matter of course, then we aren’t being honest about the adaptation challenges,” says Frumhoff of the Union of Concerned Scientists. For example, he notes, California might need to completely overhaul its water-planning efforts for the coming century if 3°C or 4°C becomes a serious possibility.

But so far, these sorts of planning efforts are scant — because few policymakers are prepared to admit that we’re going beyond 2°C.

The impossibility of staying below 2°C could also shake up the politics of climate change. After all, the UN climate talks are structured around this overarching goal. What will happen if everyone realizes it’s unreachable?

Last year, Geden, the German Institute researcher, broached this topic in a paper titled “Modifying the 2°C Target.” Then, in October, 11 researchers at the Tyndall Centre published a paper in Climate Policy exploring further alternatives to the 2°C limit. Here are a few options on offer:

Geoengineering: We could try to stay below 2°C through last-ditch “geoengineering” efforts. Some scientists have pointed out that we could, in theory, cool the Earth by putting sulfate particles into the atmosphere that reflect the sun. The downside? This could have all sorts of gruesome side effects, such as messing up global rainfall patterns. And it wouldn’t alleviate other dire impacts of our carbon-dioxide emissions, such as ocean acidification.

Accept (slightly) higher temperatures: Alternatively, policymakers could concede that 2°C is unworkable and instead work to stay below a slightly higher limit like 2.5°C or 3°C. This sounds easy: we simply accept that we’re going to face higher climate risks and try to adapt. And even if 3°C of warming is riskier than 2°C, it’s less risky than 4°C.

But there’s a hitch. As Geden points out, relaxing the limit might make global climate talks even less productive than they already are. The temperature limits themselves would suddenly be open to negotiation and endless squabbling. The Tyndall researchers worried that this could allow the world to drift into a situation where 4°C or 6°C is accepted as inevitable.

Abandoning the 2°C limit might make international climate talks even less productive

Reframe the problem: Alternatively, the world could rephrase its goals in more appealing terms. Some experts have argued that 2°C was never a particularly useful limit because it was so difficult to translate into action. The University of Colorado’s Roger Pielke Jr. has suggested that we could focus on easier-to-grasp goals like increasing the proportion of carbon-free energy that the world uses — say, going from 13 percent today to 90 percent. That would achieve similar ends, but it’s a vastly different way of framing the problem.

“It puts you in a different intellectual space, where your answers are focused on the deployment of vast amounts of clean energy,” Pielke told me earlier this year. “It’s a politics of possibility and opportunity where innovation is at the center. We may end up no better off than we are now. But the path we’re on now is going nowhere.”

Similarly, David Victor of the University of California, San Diego has long argued that starting with an agreed-upon temperature limit and then brow-beating countries into adopt the required cuts is doomed to failure. Instead, it might be more productive for countries to focus on taking individual steps on climate and slowly building up toward an agreed-upon target.

In their Climate Policy paper exploring these alternatives, the Tyndall Centre researchers noted that all of the approaches carry drawbacks — reframing the problem, for instance, could divert attention away from the dangers of higher temperatures. Ultimately, they couldn’t let go of the idea that recommitting to the 2°C limit might just be the “least unattractive course of action.” But, they noted, the world would have to take the problem much, much more seriously than it’s currently doing.

Whatever the right answer here is, the authors wrote, it’s at least something that needs to be discussed more fully. “There’s a real danger that the 2°C goal will become discredited,” says the Tyndall Centre’s Tim Rayner, one of the co-authors of the paper. “We think it’s important to begin the debate before that eventuality hits.”

[Thanks to Kim Gaddy for sending this article.]